ca. 1835–March 1899

Swimmer, Cherokee traditionalist and storyteller, was born in the Cherokee country of southwestern North Carolina. His Cherokee name, Ayunini, meant "he is swimming" or "he is a swimmer." Trained by the masters of his tribe to be a priest, a doctor, and the keeper of tradition, he never learned to speak English but instead maintained his Indian culture and heritage throughout his life. In fact, as it was intended he should be, he became the conservator of the history and traditions of his people. As a youth he learned the Cherokee Syllabary from the elders of his tribe and began early to keep a notebook in which he recorded the sacred rights as well as the facts and stories of his people. He also made note of their ways of doing things and identified plants, roots, and barks whose use had proven useful or effective in one way or another. During the Civil War Swimmer enlisted on 9 Apr. 1862 and served as second sergeant of the Cherokee Company A, Sixty-ninth North Carolina Confederate Regiment in Colonel William Thomas's legion.

In 1887 the Smithsonian Institution sent James Mooney, a former newspaperman and afterwards an ethnologist, to the Cherokee country to observe the Native Americans. Mooney had already interviewed and worked in Washington, D.C., with a Cherokee chief, and they had prepared a Cherokee grammar. During three seasons of fieldwork, he came to know Swimmer. From him Mooney collected a vast storehouse of information and in time obtained Swimmer's notebook. Swimmer perhaps recognized in Mooney a successor who would record for all time the material he had spent a lifetime in learning and recording.

Mooney, indeed, became Swimmer's link to the future. In Myths of the Cherokee and other publications, he recorded the history and the wisdom of the Cherokee that had been handed down orally for generations, while Swimmer's notebook is preserved at the Smithsonian Institution. Mooney, of course, gathered information from Swimmer's contemporaries as well, but he was careful to note with gratitude what a splendid thing Swimmer had done with his life. Swimmer had taken Mooney to tribal ceremonies, had explained ancient rites and games, had recited legends and stories, and had imitated animal sounds. (In return, Mooney rewarded Swimmer with Irish folk myths from his own childhood.) He wrote that his native friend was "a genuine aboriginal antiquarian and patriot, proud of his people and their ancient system." At dances, ball games, and other tribal functions Swimmer was always present, and he was looked to for guidance and decisions—perhaps as a referee.

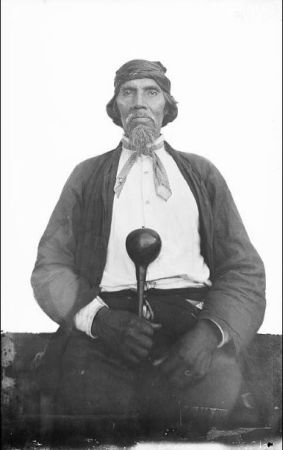

At his death at age sixty-five, he was buried on the slope of a high mountain according to the rituals of his people. Among his descendants were a son Tom (t a.mi) and a grandson called Dancer. A photograph of Swimmer, now at the Smithsonian Institution, shows him holding a gourd rattle, a badge of his authority in the tribe, and wearing his accustomed turban. He also undoubtedly wore moccasins, as Mooney observed that his head and his feet were always covered by these traditional items of dress.