d. 8 Oct. 1846 (Jacob);

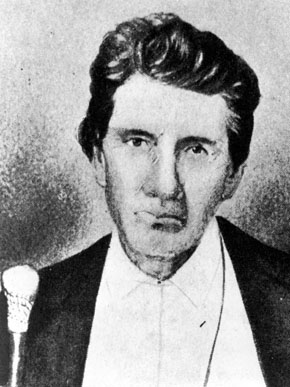

1794–1877 (Moses)

Jacob and Moses Stroup Stroup, ironworkers, came from a family of "mechanics," ironworkers, and small businessmen who were among the earliest to engage in the iron industry in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and South Alabama. As mechanics the Stroups were skilled artisans, possessing the knowledge to engage in the manufacture of iron, yet often lacking the capital to do so without backing from local merchants or planters. As such, they illustrate a phenomenon of antebellum southern industry as well as give the lie to the myth that no self-respecting southerner would engage in manual industry, or that no honor could be derived from such occupations. On the other hand, their frequent successes, failures, and moves within the South illustrate both the risk involved in industrial enterprises and the opportunities available to those not born to wealth. They also demonstrate the advantage of the mechanic—if he went bankrupt, his skills could not be taken from him, and he could start anew elsewhere. If he succeeded in turning an undeveloped site into a prosperous furnace, he could sell it for a profit, and move on to an undeveloped site farther west, develop it with his sweat, knowledge, and the capital from the previous sale, and, with good luck, become a relatively wealthy man.

The Stroups apparently were iron makers from colonial days. David Stroup was a soldier and gunmaker with the Continental army in Pennsylvania. After the war he moved to North Carolina with his fifteen-year-old son, Jacob. David and Jacob are believed to have engaged in the iron business in Lincoln County, but the records are scanty. Jacob served as an officer in the War of 1812.

Sometime in 1815 or before, Jacob moved to South Carolina and founded an iron company at the mouth of Kings Creek, on the Broad River. A flood and the death of his partner sent the company into bankruptcy, though under new ownership it operated until the Civil War. Jacob Stroup married his late partner's widow, a Mrs. Fewell, and began an ironworks nearby. This he sold in 1825 to a group of New York investors and began a new enterprise near Ninety-Nine Islands in the Broad River. While it was yet incomplete, he sold it about 1830 for $17,000. Jacob moved to Habersham County, Ga., and built a pioneer iron plant, which he sold in 1836. In the early 1840s he began a furnace at Cane Creek in Ala., with his own capital. But he reportedly lost heavily in a bad investment in a gold mine. Stroup sold the Alabama furnace in 1842, then built another in Cass County, Ga., containing a blast furnace and forge, and a sawmill. He sold this furnace to his son Moses about 1843 and began another at Altoona, which he operated until his death.

Moses Stroup, the eldest son of Jacob, was born in Lincoln County, N.C. With little formal schooling, he was brought up in the iron business. Many contemporaries considered him to be one of the "most expert furnacemen" in the South and a "remarkable genius" in the iron business, as well as a good money-maker but a "poor keeper." He accompanied his father to South Carolina about 1815, and when Jacob moved to Georgia in the late 1820s, Moses stayed behind. But in 1843 he joined his father at Cass County, Ga., and bought him out. Moses built a rolling mill and rolled some of the first railroad iron made in Georgia, some of which was used on the state-owned Western and Atlantic. In 1847 he sold the Cass County works to Mark Anthony Cooper and Company and shortly moved to Alabama, where he bought ore lands from the government and began the Round Mountain Furnace in 1849. He later moved to Tuscaloosa County, Ala., and started the Tannehill Furnace. In 1862 he sold his interest to his partner and became superintendent and manager of Oxmoor Furnaces in Jefferson County, Ala., no longer owning his own furnace but working for Daniel Pratt and others. The furnace was destroyed in the Civil War. All three of his sons, Alonzo, Henry, and Andrew, were killed in the Civil War, but he was survived by three daughters. In his lifetime he established seven furnaces and five rolling mills and at the time of his death was ready to start again.