29 Nov. 1915–31 May 1967

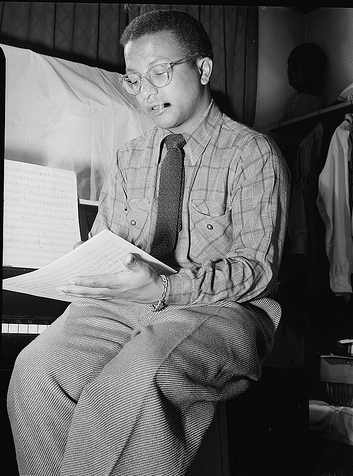

William Thomas Strayhorn, African American jazz musician, came from families (Strayhorns, Youngs, and Craigs) established in Hillsborough for generations; there seems to be some evidence of West Indian strains in his ancestry. The second son of Hillsborough natives James Nathaniel and Lillian Morgot Young Strayhorn, William (named for a Durham uncle) was born in Dayton, Ohio, but spent many months in his childhood at the Hillsborough home of his Strayhorn grandparents, Jobe, employed at the local mill as an office clerk and still remembered for his fine penmanship and manners, and Lizzie, whose flower garden where the child played is said to have furnished imagery for his later lyrics. This grandmother, Strayhorn told an interviewer, was the primary influence during his first ten years, and her house his first real home. There his musical precocity surfaced very early when, as a preschooler, he learned to play hymns on her piano and to pick out any Victrola record requested. His first year of school was in a Hillsborough building later destroyed, with all its records, by fire.

His education continued in Pittsburgh, where his family settled and his father entered the construction business. Aware of the boy's gifts, the parents provided him with private music lessons and sent him to the Pittsburgh Musical Institute, where he studied classical music. At Westinghouse High School, he played in the school band and attended the classes of the same teacher who had instructed jazz pianists Mary Lou Williams and Errol Garner.

By Strayhorn's own account, a Pittsburgh performance by the band of the well-established jazz musician Duke Ellington dazzled and inspired the eighteen-year-old boy, then employed as a soda fountain clerk. He formed a trio that played daily on a city radio station, and he composed three songs with lyrics: "My Little Brown Book," "Something to Live For," and "Life Is Lonely," later famous under the title "Lush Life" and judged by a jazz authority in 1968 as a sophisticated work that alone qualified its writer for a place in an exclusive hall of fame.

When Ellington returned to Pittsburgh four years later, a friend persuaded Strayhorn to seek an audition at which he played these compositions. Impressed, Ellington took "Something to Live For" and recorded it three months later; the resulting praise prompted him to send for Strayhorn, who joined him in New Jersey as a promising protégé with a vague appointment to write lyrics for Ellington's songs. By the end of the year, Strayhorn was scoring most of Ellington's small band dates and beginning to arrange and compose for the full band. His lifelong collaboration with Ellington had begun.

Described by a historian as "without parallel in the history of jazz and possibly of all music," this remarkable partnership between Ellington the famous and flamboyant cosmopolite and Strayhorn the modest provincial sixteen years his junior merged the gifts of both into what appeared to many observers to be one creative musical organism. They composed together so spontaneously and interdependently—sometimes even by long-distance telephone—that it was said, "Neither was sure at times who contributed what to a finished piece." Many of Strayhorn's compositions were attributed to Ellington, partly because his fame ensured an audience and sales and partly because neither man genuinely cared so long as the music was written, performed, and heard as widely as possible. In time, even their piano playing was indistinguishable except to experts, a phenomenon that puzzled the partners, who considered their styles distinctly different. Strayhorn maintained that Ellington's real instrument was his band, through which he melded the many instrumentalists (including an extraordinary number of top-ranking performers) into a varying whole that produced what was called the unmistakable "Ellington sound." Strayhorn and Ellington wrote for this instrument as its components changed when musicians joined the band and left it. Strayhorn is credited with discovering Jimmy Blanton, who revolutionized the role of the bass. In addition to composing music and lyrics, Strayhorn did arrangements and orchestration for the band and sometimes substituted for Ellington at piano. His marked indifference to attention, publicity, status, credits, and money in a profession in which such goals are avidly pursued made it notoriously difficult to lure him to recording studios or concert stages for star performances, with the result that recordings of these rare events are now treasured by collectors.

In his first two years with Ellington, Strayhorn composed "Day Dream," "Like a Ship in the Night," "Savoy Street," "You Can Count on Me," "Minuet in Blue," "Passion Flower," "Raincheck," and "Chelsea Bridge," inspired by Whistler's painting of Battersea Bridge but misnamed by the composer in a confused moment at a recording studio. To this period belongs his most popular work, "Take the A-Train," which he termed a set of directions on how to take this Eighth Avenue express from 59th Street in Manhattan to 125th Street in Harlem, at that time a yeasty African American cultural mix of musicians, writers, entertainers, and sports champions. Ellington, who had got his start there, adopted this as his theme song. (Later, Strayhorn's "Lotus Blossom" became the band's sign-off song.) Strayhorn also during this apprenticeship wrote the lyrics for "I'm Checkin' Out," "Lonely Co-ed," "Tonk," and "Your Love Has Faded"; did the arrangement of "Flamingo"; played piano for recordings; and conducted a series of small band dates.

The vicissitudes of World War II affected the band adversely at first but indirectly brought it its first Carnegie Hall concert in 1943, when Strayhorn's "Johnny Come Lately" and "Dirge," said to resemble Milhaud and Stravinsky, were performed. At the next Carnegie concert, in 1944, Strayhorn's "Strange Feeling," from Perfume Suite, was presented, and in 1946, the Strayhorn-Ellington Deep South Suite , of which only one piece has survived. Esquire magazine gave Strayhorn its Silver Award for arranger that year, and in the same capacity he won the poll conducted by the jazz periodical Down Beat .

Strayhorn went to Europe for the first time in 1950, when the band had a French tour. His work received admiring attention, and after that he visited Paris as often as possible, becoming fluent in French and something of a cult figure. In Chicago his "Violet Blue" was featured at a band performance at the Civic Opera House and also in New York at a benefit concert for the NAACP at the Metropolitan Opera House, along with "Take the A-Train."

Mixed reviews met the work A Drum Is a Woman, with music, lyrics, and arrangement done by Strayhorn and Ellington in 1956, but their most ambitious undertaking was a decided critical success in 1957: the Shakespearean Suite, also entitled Such Sweet Thunder (from Midsummer Night's Dream), composed for the Shakespeare Festival at Stratford, Ontario. Both men read the plays in toto, discussed them with experts, and devoted serious attention to their selection of themes, producing a total of twelve compositions with such titles as "Sonnet in Search of a Moor," "Sonnet to Hank Cinq," and "Star-Crossed Lovers." Conservatives who complained of levity were told that this suite, like the plays, threaded tragedy with comedy.

"Toot Suite" and "Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald" followed, and then another European tour, to France and to the Leeds Festival in England. There the musicians met Queen Elizabeth II, and Prince Philip, at the first performance, mentioned his regret at having missed their rendition of his favorite, "Take the A-Train." Strayhorn and Ellington later wrote The Queen's Suite , of which Strayhorn alone composed the section "Northern Lights," intended to convey majesty; the single recording pressed was presented to the queen.

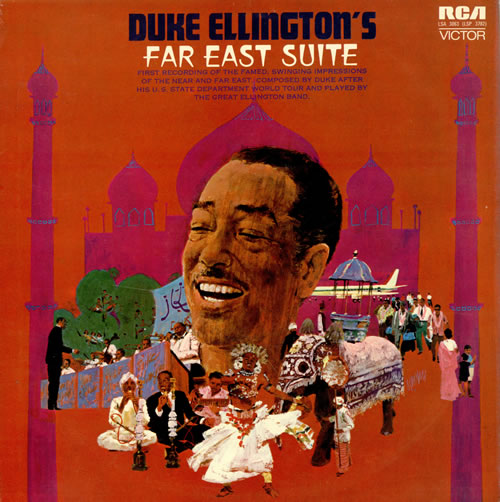

Strayhorn wrote "Multi-Colored Blues" for the recording Newport 1958, and much of Suite Thursday, commissioned by the Monterey (Calif.) Jazz Festival to be based on John Steinbeck's novel Cannery Row. The British periodical Melody Maker chose Strayhorn's arrangement of Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite as its jazz LP record of the year 1960. The partners' Peer Gynt Suite appeared in 1962, and in 1963 Strayhorn supervised the performance and played piano at the presentation of Ellington's My People during the Century of Negro Progress Exposition in Chicago. That autumn the band set off for the Middle East on a tour sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, according to its then current policy of sending American musicians abroad as universally understood messengers of the national culture. Given VIP status, they were entertained by American diplomats at high-level social affairs attended by the royalty, diplomatic corps, and artists of the host countries. Concerts were given in Damascus, Jordan, Jerusalem, Kabul, and New Delhi, where Strayhorn, his patience frayed by the attempts of reporters to bait the band members about the racial situation in America, sharply reminded them that the subject at hand was music. When Ellington fell ill, Strayhorn took over the piano playing at concerts in Hyderabad, Bangalore, Bombay, and Madras, where his skill evoked an enthusiastic review in the Indian Express . The tour continued to Dacca, Lahore, and Karachi, where Strayhorn ventured off to see the Taj Mahal; and to Teheran, Isfahan, Abadan, Kuwait, Baghdad, Beirut, and Ankara, where the news of President John F. Kennedy's death abruptly terminated the tour.

A Japanese tour in 1964 completed Strayhorn's experience of Asia. The result was the Strayhorn-Ellington Far East Suite , of which "Agra," celebrating the Taj Mahal, is Strayhorn's. A Caribbean tour prompted the Virgin Island Suite by both men.

Now known to be gravely ill, Strayhorn allowed himself to be coaxed onstage at the Pittsburgh Jazz festival in 1965 to play a piano version of "Take the A-Train." The New York chapter of the Duke Ellington Jazz Society presented him to a packed audience at the New School auditorium, where he played a selection of eighteen of his pieces and then, with some other band members, representative joint works of the partners.

His last composition, "Blood Count," written while he was hospitalized for cancer of the esophagus and presented at Ellington's 1967 Carnegie Hall concert, was finished not long before he died. A private family funeral at St. Peter's Lutheran Church in New York preceded a large one given by Ellington and attended by friends and colleagues in musical, theatrical, and film circles. The body was cremated and the ashes scattered, as Strayhorn's will directed, on the Hudson River by the Copasetics Club, a charity organization founded by Billy (Bojangles) Robinson for show business members who donated their services for the benefit of African American children in the South. Strayhorn was its second president, and after his death the club honored him by refusing to have another with that title; its chairman is called vice-president.

Nicknamed "Willie" and "Swee'pea" (for the baby in the cartoon strip Popeye because of Strayhorn's small five-foot-three-inch stature), he is credited by Lena Horne, his close friend, with contributing greatly to her musical education, particularly in regard to classical music, during their many hours together. He cited as his reasons for never marrying both his frenetic activities as a jazz musician traveling to concerts, dances, theaters, clubs, and recording studios on three continents, and his impulsive mode of life, incompatible with domestic order. Coteries of admirers formed in Paris, Helsinki, Stockholm, and London. Influenced by Ravel, Stravinsky, Debussy, and Rimsky-Korsakov, his work was more celebrated in Europe, where jazz was taken seriously as an art form, than in America. His music has been called "sheer and shimmering in quality," "gentle, reflective melodies in minor moods" and "pastel colors."

In 1968 the Ellington band recorded a Strayhorn album, And His Mother Called Him Bill , consisting of eleven Strayhorn compositions and, at the end, an unscheduled and spontaneous solo by Ellington at piano of "Lotus Blossom," the sign-off song, which an alert studio technician fortunately caught. This final tribute was acclaimed by jazz critics, an unsentimental lot, as both impeccable and moving.

Strayhorn has been termed an éminence grise, a genius, a legend, one of the nation's top composers and arrangers, and the most revered figure in jazz. Even if the puffery is discounted, his prestige not only remains but also continues to grow in the present jazz revival. The fame he never sought has increased since his death.