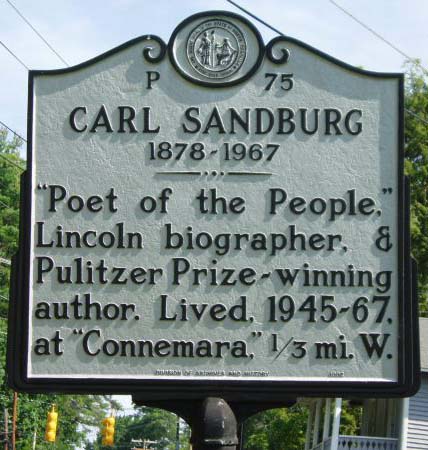

6 Jan. 1878–22 July 1967

Carl August Sandburg, poet, journalist, biographer, and folk song recitalist, was a national celebrity long identified with the Midwest when he moved to North Carolina in 1945 after purchasing the historic Connemara Farm at Flat Rock. In 1958 the legislature made him "Honorary Ambassador" of the Old North State.

Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Ill., the second child of pious Swedish immigrants. His father, unable to write, is believed to have changed the family name from Johnson shortly after beginning work as a blacksmith's helper in the C. B. and Q. railroad shops. His mother was the former Clara Mathilda Anderson. Leaving school after the eighth grade, Sandburg held an array of humble jobs in Galesburg and then bummed his way as a hobo westward as far as Colorado, with intervals of labor in harvest fields or washing dishes in grubby restaurants. These early adventures are colorfully described in the portion of his autobiography entitled Always the Young Strangers (1953). In 1898 he was back in Galesburg and working as a painter's apprentice when he enlisted in the Sixth Illinois Regiment; Sandburg served briefly in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War.

With a veteran's privileges he entered Lombard College, a tiny Universalist school in Galesburg; flunked the examinations required for admission to West Point after being nominated by an army friend; and resumed studies at Lombard until 1902, when he left without graduating. His four years at college were crucial, for there he was stimulated by musical, forensic, and literary activities and hailed as a genius by a professor named Philip Green Wright, who introduced him to the arts and crafts movement of Ruskin, Morris, and Elbert Hubbard and encouraged his social radicalism then bordering on Syndicalist Anarchism. The professor also operated an arty press in his basement where he published four little volumes of Sandburg's juvenilia, beginning in 1904. Rudyard Kipling and standard favorites of the nineties were major influences on Sandburg's early verse, but independently he had come across Walt Whitman, whose free verse he imitated until a decade later he mastered his own version of that medium.

Another period of wandering followed departure from college; this time he went to the East to sell stereopticon pictures. With the muckraking fervor then in full swing, socialism burgeoned and new periodicals multiplied. Sandburg took to the hustings as an organizer for the Socialist party and acted as press secretary for a Socialist mayor of Milwaukee, but after his marriage on 15 June 1908 he was more the journalist than poet or politician. His wife was Lillian Steichen, a high school teacher and a Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Chicago—also an ardent Socialist. Her brother, Edward Steichen, later a famed photographer, became a potent influence on Sandburg's views of art. The Sandburgs had three children, Margaret, Janet, and Helga, the last-named also a writer. Another daughter died in infancy.

In 1912 the poet returned to journalism in Chicago, shifting from post to post with magazines and newspapers until he eventually found a niche on the Daily News, an afternoon paper for which he worked on and off for many years as labor reporter, movie critic, editorialist, or columnist. His divorce from the Socialist cause became greater as the party split over the entrance of the United States into World War I. Sandburg thereafter called himself an independent and in time heartily endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. Later he was on close terms with Adlai Stevenson and Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

A sturdy family man, Sandburg avoided the bohemian excesses of the artistic crew active in Chicago, then in an era of remarkable crescendo, but soon was propelled into prominence by being hailed as one of the first "finds" of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, whose establishment in 1912 is often regarded as a wellspring of the "New Poetry." The editors of this Chicago journal awarded him their Levinson Prize and prompted a New York publisher to bring out his Chicago Poems (1916), previously printed in Poetry, Socialist sheets, and elsewhere. Unconventional subjects, slang, "realism" of the ashcan sort laced with wistful flashes of beauty, and a kind of chanting music quickly made his free verse famous in advanced quarters and notorious in conservative purlieus where "shredded prose" was the slogan of stigma. "Chicago," "Fog," "Nocturne in a Deserted Brickyard," and other poems in the volume remain his best-known pieces. The most popular, "Fog," was an effort to emulate the Japanese Haikku and was written in the anteroom of a police court judge whom Sandburg was sent to interview. On the way he had stopped to look at the dense mist gathering over the Chicago harbor. Similar odd moments in the turmoil of journalism produced much of his subsequent verse. And the style remained unchanged.

Cornhuskers (1918), Smoke and Steel (1920), Slabs of the Sunburned West (1922), Good Morning, America (1928), and The People, Yes (1936) in chronology illustrate the rise and fall of the "Poetical Renaissance" in which Sandburg was a major figure. The People, Yes was his longest poem—teeming with proverbs, wisecracks, and other sorts of folklore picked up during his travels or sent in for his newspaper column. It is as choice a sample of affirmative Americana as the depression era produced; "it attempts to give back to the people their own lingo," as its author stated. Sandburg was scarcely a young man when he vaulted into the sky of the New Poetry, and when in 1950 his Complete Poems appeared, without selection or revision, there were few additions to the above-named volumes, and these were chiefly poems of occasion. Two subsequent collections appeared as Harvest Poems: 1910–1960 (1960) and Honey and Salt (1963), the latter containing several pieces revealing his deep and abiding affection for his wife.

Fame as a poet with the ensuing honors and prizes cannot keep lupus americanus from the door, however. Sandburg continued to work for the press and in 1918 went to Scandinavia as correspondent for the Newspaper Enterprise Association; when this syndicate later fired him, he took refuge again with the News. In 1922 his whimsical tales for his children were revamped as Rootabaga Stories, to be followed by Rootabaga Pigeons (1923). Altogether, he put out five subsequent books for the young, including appropriate segments of his autobiography and his study of Abraham Lincoln. More remunerative were his lectures. Beginning in the 1920s, when the colleges turned to the "new" poetry, Sandburg soon was recognized as a surefire entertainer—a superb platform artist who could read his poems to perfection, reel off a "Rootabaga" yarn, provide a store of belly-shaking mirth, temper the mood with a bit of fetching philosophizing, and top off with a round of work songs, new and old, sung in a rich baritone accompanied by his guitar. His taste as a collector of songs is to be seen in his anthologies The American Songbag (1927) and The New American Songbag (1950).

Indulgence to a celebrity by his newspaper bosses and his lecture tours enabled Sandburg to cut down on hack work and to spend more time composing at a summer cottage at Tower Hill, Mich., to which he later moved from the Chicago area. As the popularity of contemporary verse faded with the public, a new rage for long-winded biographies flourished. It was such a biography that enabled Sandburg to own the summer place as a permanent home, to buy expensive animals to gratify the goat-breeding hobby of his wife, and to possess six guitars. His monumental work on Lincoln, originally conceived as another book for young people, came in two installments, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). This six-volume opus was so widely proclaimed that its author passed from the region of famous poets to the empyrean of movie stars. Honorary degrees now came in showers, reporters eagerly sought his views on current topics, public schools were named for him, and Democratic presidents were flattered when he wrote them letters saying that Abraham Lincoln would have approved of their actions.

In addition to broadcasts and news reports, Sandburg's offerings on the Lincoln shrine numbered a one-volume redaction of the full biography (1954), a book on Mary Lincoln, another on the photographs of the Emancipator, and a third on a noted private collection of Lincolniana. Others did most of the work on these last. In 1959 Lincoln's birthday was celebrated in Washington by a solemn gathering of Congress, the Supreme Court, the Eisenhower cabinet, and the diplomatic corps. The choice of Sandburg as chief speaker for the occasion constituted a unique honor.

During World War II he patriotically defended U.S. policies, helped with propaganda in the various news media, and even took on for a while a column for the Chicago Daily Times. In 1959 he went on a mission to Russia for the Department of State.

After settling in North Carolina his most extensive publications were a huge panoramic novel Remembrance Rock (1948) and the autobiographical Always the Young Strangers, one of his best books. The reaction to the novel was at best merely polite. But a first novel by a man seventy years old, planned to be a movie "spectacular" intended to arouse a sense of patriotism, can hardly be expected to lay a claim to immortality.

Of Sandburg's enormous production of labor news, miscellaneous journalism, scripts, and so forth, You and Your Job (1908), The Chicago Race Riots (1919), and Home Front Memo (1943) offer samplings. It was only during his last few years that he did not have a finger in some sort of project. When death came, the tributes were front-page items. After a family service at Flat Rock conducted by a Unitarian clergyman, his body was cremated and the ashes were buried at Galesburg. In a special ceremony held in Washington at the Lincoln Memorial, President Johnson spoke of him as "the echo of the people." Of all the encomia Sandburg probably would have like that one best.

In 1956 Sandburg sold his papers, proofs, and library to the University of Illinois. To date this collection lacks his own letters, a selection from which, however, was indifferently edited by Herbert Mitgang (1968).