April 25, 1908 - April 27, 1965

See also: Edward Roscoe Murrow, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography

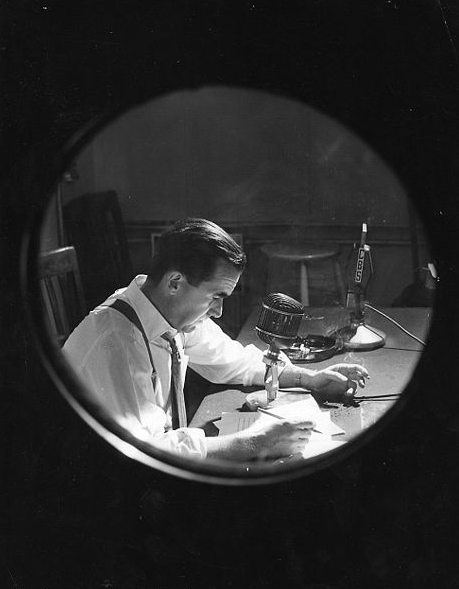

Edward R. Murrow set the standard for television journalism that continues to challenge and inspire today's television newspersons. His calm and courageous reporting captured our nation's and the world's attention during the German Blitz of Great Britain in 1940 and 1941 and remained firm while confronting the paranoia of McCarthyism at home in 1954. Although a figure of great importance in journalism, Murrow hailed from modest beginnings near Polecat Creek in Guilford County, North Carolina.

Born in the neighborhood of another famous North Carolinian, O. Henry, Edward R. Murrow was born as Egbert Roscoe Murrow on April 25, 1908. The Murrow homestead stood in a Society of Friends community, and Roscoe and Ethel Murrow enforced the Quaker prohibition of smoking, drinking, and gambling upon their children. Murrow worked the family farm with his brothers Dewey and Lacey and enjoyed listening to his grandfathers' memories of their Civil War experiences at Gettysburg and Manassas. The Murrow family moved to Blanchard, Washington when Egbert was six, seeking a more prosperous life in the lumber industry. The family returned to Guilford County after a year, but in 1925 once again relocated to Washington. His early years near Greensboro held pleasant memories for Murrow who would make frequent returns to his piedmont home throughout his life.

Murrow began his collegiate career in 1926 and set in motion a series of important events that would mold him into a great journalist. He attended three separate universities: Leland Stanford University, the University of Washington, and Washington State College. By the time he graduated, Egbert R. Murrow had changed his name to Edward R. Murrow. Aside from working while enrolled at Washington State, Murrow was class president and top cadet of the university's ROTC program. Murrow was also an active member of the National Student Federation (NSF).

After graduating in 1930 with a major in speech, Murrow was elected president of the student organization and expanded its activities by visiting hundreds of colleges and universities in the United States and Europe, establishing a student travel bureau and arranging for international student debates. He was also able to persuade the fledgling Columbia Broadcasting Service (CBS) to air a program entitled "A University of the Air." Murrow was able to recruit such well known personages as Albert Einstein and German President Paul von Hindenburg for appearances on the program.

While traveling to New Orleans for a NSF conference, Murrow met Janet Brewster, a student from Middletown, Connecticut, who would be attending the same conference. Brewster and Murrow were married in 1934, and had one son, Charles Casey. The newlyweds visited the Murrow homestead in Guilford County. Murrow related memories of this North Carolina trip to a fellow correspondent during the 1941 German blitz of London, "I once took my wife through Carolina on a trip, and she always wanted to go again, which is proof of sound judgment."

In 1935, Murrow joined CBS as Director of Talks and Education but was transferred as chief of the European Bureau two years later to London. Initially his task in London was to arrange cultural programs, but the coming of World War II dramatically changed his role. Murrow made a special trip to Vienna in 1938 to report on the entrance of the Nazis into the Austrian capital, "Herr Hitler is now at the Imperial Hotel. Tomorrow, there is to be a big parade.... Please don't think that everyone in Vienna was out to greet Herr Hitler today. There is tragedy as well as rejoicing in this city tonight." When war was declared, Murrow reported firsthand, beginning his broadcast with the phrase that would become his hallmark, "This is London."

Many of Murrow's broadcasts during the Battle of Britain were punctuated by the sounds of air raid sirens or bomb explosions. The CBS offices in London and the BBC studios from which Murrow made his broadcasts were bombed at least once. On at least one occasion, he broadcast from the roof of a building during a raid to report an eye witness account of what Britain was enduring. A selection of Murrow's broadcasts from 1939 to 1940 were published in 1941 under the title This Is London. Murrow returned to the United States at the conclusion of the war in 1945 and was promoted to Vice-President of News, Education, and Discussion Programs, but he resigned the position in 1947. Later that same year, Murrow resumed broadcasting and was elected a Director of CBS in 1949.

The year 1950 brought the beginning of the Korean war, and Murrow traveled there to report the events. The reporter presented weekly digests of news called Hear It Now which was based on the format of an earlier project, I Can Hear It Now. I Can Hear It Now presented history through recorded speeches and news broadcasts of the featured event and was produced by Murrow and Fred W. Friendly. The success of I Can Hear It Now and Hear It Now led to the creation of See It Now which translated the established format to television.

See It Now became very popular by bringing the public into such previously unfilmed areas as a submerged submarine, a fighter plane during air defense exercises, and a session of the Arkansas General Assembly. During the creation and rise of See It Now, Murrow continued to report the news in Korea. His reports mentioned the major events of the day but also focused on the individuals caught up in the sweep of events. Murrow won widespread acclaim for his manner of relating the life of the common soldier in Korea. In "This Is Korea ... Christmas 1952," a broadcast of the See It Now program, Murrow's work moved a commentator of the New Yorker magazine to call the program, "One of the most impressive presentations in television's short life." The See It Now program spotlighting Senator Joseph McCarthy (March 9, 1954) earned Murrow a Peabody Award and is viewed as a turning point in the "Red Scare."

We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason if we dig deep in our history and remember we are not descended from fearful men ... who feared ... to defend causes which were unpopular .... The actions of the junior senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay ... and whose fault is that? Not really his; he didn't create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it, and rather successfully. Cassius was right, "The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves."

(Excerpted from the March 9, 1954 See It Now broadcast, as quoted in In Search of Light: The Broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow 1938-1961, pp 247-8.)

See It Now was also selected "Program of the Year" in 1952 by the National Association for Better Radio and Television, and won an "Emmy", a Look-TV Award, a Sylvania Television Award, and a Variety Showmanship Award. Aside from this successful program, Murrow began Person to Person, Small World, and CBS Reports.

In 1960, Murrow produced Harvest of Shame, which depicted the many hardships that plague migrant farm workers. Aired on Thanksgiving day, Murrow's documentary shocked the country, and brought a call for legislation to protect the workers whose labor helps to fill supermarket shelves.

Murrow's success in broadcasting and television production made him a household name. He was in great demand as a public speaker and was given honorary degrees by five colleges, including an honorary law degree from the University of North Carolina. Retiring from CBS in 1961, Murrow took the controls of the U.S. Information Agency. He held that position until 1964 when he retired due to lung cancer. Edward R. Murrow died on April 27, 1965, at the age of 57, on his farm in Pawling, New York.

Edward R. Murrow brought the dramatic events of the nation and world into the homes of millions. He covered these events with a simple and strong grace that was not pretentious. His early years in and frequent visits to North Carolina kept him close to his beginnings. A tradition of verbally relating history from his grandfathers planted the seeds of journalism that were to grow through Murrow's collegiate career and blossom in the dark years of World War II. His courage allowed him to tell the world of the events of the German Blitz of London while it was happening and also to publicly face paranoia at home over a decade later. He used television as a medium to include and educate the public in the movements of governments and culture. In the formative years of television, Murrow established a high standard of professionalism and quality that continues to challenge modern broadcasters.