10 Oct. 1917–17 Feb. 1982

Thelonious Sphere Monk, jazz musician and composer, was born in Rocky Mount, the son of Thelonious and Barbara Batts Monk. When Monk was four, his mother took him and two other children to New York, while his father remained in the South. In the early 1930s the family moved into a small apartment in Manhattan, the city where Monk spent most of the remainder of his life. His residence through most of this time was an apartment on West 63rd Street.

Largely self-taught as a musician, Monk started his musical activities by age six, and at ten he began playing an old piano that belonged to his grandparents. Additional valuable experience was obtained when he accompanied his mother's singing at their local Baptist church in New York. One of his first jazz idols was Louis Armstrong, while major influences on his early musical development included Earl "Fatha" Hines, Art Tatum, Fats Waller, James P. Johnston, Willie Smith, Jimmy Yancey, and especially Duke Ellington. As a teenager in Harlem during the depression, Monk developed his highly personalized style of skewed melodies and oblique harmonic progressions. During the late 1930s he played the piano with traveling evangelist shows and in brief gigs around New York City, eventually settling in 1939 with Keg Purnell's quartet.

Monk's emergence as an accomplished jazz pianist occurred during his association with Minton's Playhouse at the Hotel Cecil on 118th Street in Harlem, where in 1940 saxophonist Henry Minton converted a run-down dining room into a jazz club that featured avant-garde improvisation and freewheeling jam sessions. Kenny Clarke organized the first band at Minton's Playhouse, with Monk as the pianist of the group. It was at Minton's and at the Uptown Club that Monk thus became part of the small group of musical innovators whose harmonic and rhythmic explorations spawned the angular breakaway from conventional jazz known as "bebop" or "bop." Although this episode in American jazz has become somewhat romanticized, most of the musicians involved in the events apparently did not consider that they were doing anything unusual or self-consciously creative but merely "playing a gig" for fun and money.

In the early years, particularly at Minton's Playhouse, Monk worked with such leading jazz figures as trumpeter John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie and alto-saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker, as well as Charlie Christian, Joe Guy, and Nick Fenton. At other times during the 1940s he was a member of bands headed by Lucky Millinder (1942), Kenny Clarke (1942), Scotty Scott (1943), Coleman Hawkins (1944), and Cootie Williams (1944). Between 1947 and 1952 Monk produced a series of recordings on the Blue Note label, a collection that remains among the most significant and original in modern jazz.

Although his asymmetrical and complex musical ideas exerted a profound influence on an entire generation of jazz musicians, Monk himself had slipped into virtual obscurity by the early 1950s. His career suffered a major setback during this time, when his cabaret card, a prerequisite for employment in establishments serving liquor, was revoked for six years due to an allegedly unjustified charge involving drug violations. Thus, from 1951 to 1957 Monk was only rarely able to obtain paying jobs in New York.

In the middle and late 1950s, however, he reemerged with new popularity, aided by critically acclaimed recordings with John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. In 1954 he produced important albums with Rollins, Percy Heath, Art Blakey, Julius Watkins, Miles Davis, and Milt Jackson. The turning point came in 1957, when Monk released his album Brilliant Corners, the first Riverside issue containing his original compositions. Later that year, through the assistance of the Baroness de Koenigswarter, Monk was able to obtain a cabaret card, thereby permitting him to resume paid engagements in New York City. In the summer of 1957 Monk brought together at the Five Spot Cafe a quartet including himself, John Coltrane, Wilbur Ware, and Shadow Wilson. This now legendary engagement, which continued through New Year's Eve 1957, paved the way for Monk's rediscovery as a major figure in modern jazz.

Monk appeared on CBS-TV in December 1957 in the "Sound of Jazz," while in April and May 1958 he was engaged at the Village Vanguard. Subsequently, he was chosen as the outstanding international jazz pianist in 1958, 1959, and 1960 and was elected to Down Beat magazine's Hall of Fame. Monk appeared in the Randall's Island Detroit Jazz Festival and at Town Hall in 1959, at Philharmonic Hall in 1963, and at Carnegie Hall in 1964. During the last half of the 1960s, he led a quartet that toured widely at clubs, festivals, and concerts around the world. In 1971 and 1972 Monk toured Europe performing with a group called the Giants of Jazz, which included Sonny Stitt and Monk's old colleague, Dizzie Gillespie. Semiretired after the tour due to health problems, Monk later performed a concert of his music at Carnegie Hall on 6 Apr. 1974 for the New York Jazz Repertory Company and at the Newport Jazz Festival in New York in 1975. He received a special tribute from President Jimmy Carter in 1978 during a jazz concert at the White House.

Monk created more than seventy jazz compositions, of which his early ballad, "Round Midnight," remains perhaps his best-known piece. Other recognized works included "Epistrophy," "Blue Monk," "Off Minor," "Straight, No Chaser," "Well, You Needn't," "Four in One," "Ruby My Dear," "I Mean You," "I Should Care," "Misterioso," "Evonel," "Criss Cross," "Hackensack," "Trinkle Tinkle," "We See," "Locomotive," "Reflections," and "Crepescule with Nellie." He also composed the musical score for the film Les Liaisons Dangereuses and appeared in the movie Jazz on a Summer's Day. At various times in his career he recorded for Blue Note (1947–52), Prestige (1952–55), Riverside (1955–59), Columbia, Everest, Jazzland, and Savoy.

A major reason for the uniqueness of Monk's contribution is that, to a greater extent than any other musician of his time, he created music that originated completely from within jazz. Most other important composer-pianists have borrowed, with varying degrees of successful assimilation, from formal European music, thus giving the listener an unconscious feeling of ease and familiarity with their work. With Monk's compositions there is no such convenient handle to the music; they create a distinctly different impression from that experienced in listening to most other modern jazz works.

His compositions are angular, complex, and difficult to play. One critic characterized his music as possessing "dissonances and rhythms that often give one the sensation of missing the bottom step in the dark." Monk's melody and harmony lines are so integrated structurally that it is almost impossible for soloists to improvise on the chord sequences alone. His original themes, characterized by rhythmic displacements and irregular structures, are considered among the most unusual of jazz forms, while his compositions often possess melodies of great harmonic charm. Monk usually based his writing on conventional, formalized twelve and thirty-two bar structures, such that the distinctive aspect of his work rests in the melodic originality and harmonic substructures. His rhythmic virtuosity is characterized by mastery of displaced accents, shifted meters, shaded delays, anticipations, silence, and pauses, yet his work remains highly structured and ordered, typically providing a striking sense of emotional and artistic completeness in each piece. Although his compositions are regarded as his most important contribution to jazz, Monk's extraordinary mastery of piano technique, with the stark somber quality and unique dynamics of his playing, made him among the most influential and popular figures in jazz.

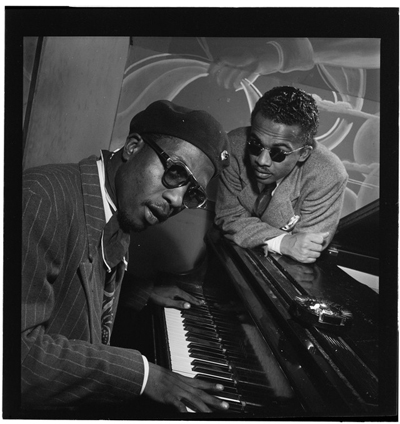

Monk was a distinguished-looking man, over six feet tall and massively built, who usually dressed rather elegantly and sported a black Vandyke beard, bamboo-framed sunglasses, and a skullcap, which combined to give him a ferocious appearance, despite being known as a kind and gentle person. He died in Englewood, N.J., following a stroke. He was survived by his wife, Nellie, and two children, Thelonious, Jr., and Barbara "Booboo" Monk. Portraits appear in many articles in Down Beat, in his obituary notices, and in Valerie Wilmer's Face of Black Music (1976).