27 Dec. 1883–14 May 1975

William Thomas Laprade, educator, historian, and editor, was born in Franklin County, Va., the son of Mary Elizabeth Muse and George Washington Laprade. The family had long owned a mill on Snow Creek, near Penhook. His father subscribed to Watterson's Weekly Courier-Journal, which had a "Young Writer's Department" for the pseudonymous correspondence of young people. Using the pen name "Jebird," Laprade wrote letters and short stories and even tried his hand at poetry. Under the influence of local ministers and Sunday school, he became a Campbellite preacher and in 1904 entered Washington Christian College (no longer in existence), Washington, D.C. He graduated in 1906 and then remained as associate professor of mathematics and Latin from 1906 to 1907. Concurrently, he was a teacher, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, and minister of the Antioch Christian Church near Vienna, Va. In June 1908 he made the first of many trips to England, and in 1909 he received a Ph.D. degree from Johns Hopkins with a dissertation on "England and the French Revolution, 1789–1797."

In the fall of 1909 Laprade landed at Trinity College (now Duke University), more by accident than choice, to become the first full-time professor of European history in North Carolina. Here he remained except for brief stints as a visiting professor at the University of Illinois (1916, 1930), the University of Pennsylvania (1925), and the University of Michigan (1929). For a few years he also occasionally preached. On 11 June 1913 he married Nancy Hamilton Calfee, a former student at Washington Christian College. Their only child was Nancy Elizabeth (Mrs. J. D. T. Hamilton).

Laprade was manager of the college "Book Room" from 1912 to 1926. He spent parts of 1926 and 1927 in England and acquired many important English books for the Duke Library. He was the first editor of the Trinity College Press (1922–26) and later acting director of the Duke University Press (1944–51), as well as managing editor of the South Atlantic Quarterly (1944–57). He was chairman of a growing history department from 1938 to 1953.

Active off the campus, Laprade was a "Minute Man" speaker during World War I, and he enjoyed lecturing on history and politics to business and professional men at the YMCA training school in Blue Ridge, N.C. (1918–19). He belonged to several civic clubs and was a charter member (president, 1926) of the Kiwanis Club. He was a member of the North Carolina Commission on Inter-racial Relations (1919–42), the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association (president, 1937), and the executive board of the Department of Archives and History (1941–60). Active in the American Historical Association and other professional organizations, he was initiated into Phi Beta Kappa (1909) and the Royal Historical Society of Great Britain (1926).

Undoubtedly his most important work—aside from editing, writing, and teaching—was with the American Association of University Professors. He was president from 1942 to 1943; from 1937 to 1942 and again from 1948 to 1953 he was chairman of Committee A, on Academic Freedom and Tenure, the most important committee of that organization at a time when repressive influences threatened the academic world. For the chairman, difficult and sometimes awkward problems involved a heavy correspondence, the appointment of committees of investigation, and final reports. Subsequently, Laprade wrote a special report on the work of Committee A from 1916 to 1953. Elsewhere he said that however elusive truth might be, its best hope was "unfettered, honest, intelligent inquiry." The "tyranny of an authoritarian government" was so "appalling" that "no sacrifice would be too great . . . to avert such a fate." Laprade was recognized as one who spoke with the voice of moderation and reason no matter how great the crisis. He had a reputation for both wisdom and practicality.

An effective teacher and something of an actor, Laprade (privately known to his students as "Lap") had the knack of connecting topics of current interest with historic events to show that the study of history was indeed relevant. It was "not the business of college professors to provide their students with opinions," he said; rather they would provide them with "the knowledge, and the training which will enable them to form and defend opinions of their own." His lectures to graduate students on his specialty, eighteenth-century England, were without formal notes and nearly always accompanied by brief illustrative readings from selected sources. He was at his best in the research seminar, which met at his home where his wife prepared refreshments. Students reported on assigned topics with fear and trembling, for they knew any weakness would be shrewdly dissected. They also knew they were learning a good deal about historical method. Laprade thought history more an art than a science, that it permitted a look at the past that could be had in no other way, and he was careful never to be dogmatic about the lessons of the past. He thought of society as a complex whole with many interrelations that precluded an easy division into political, economic, and social phases. Thus he did not believe in economic determinism, but he learned that he who held the purse called the tune. A student of public opinion and especially the press in both olden and modern times, he concluded: "Newspapers are both monopolistic public utilities and dispensers of merchandise. . . . In the general interest they may require a measure of regulation as well as freedom." He had a skeptical view of the molders of opinion, whether organized groups, the media, or government.

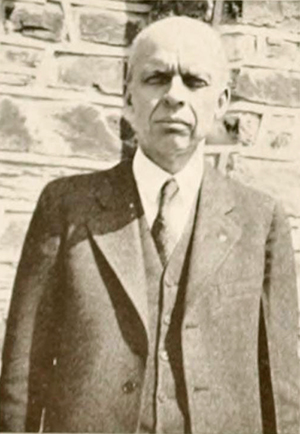

In his later years, Laprade was slightly stooped, though he was above medium height. The grayness of his office pallor and scanty white hair was relieved by the mobile countenance and ready laughter. He was inclined to a lean physique, and his only known exercise was walking. Regularly he could be seen striding from his home near the East Campus to the city post office for the several newspapers he read, or to the grocery where he did most of the family shopping. He was remarkably healthy and was never a hospital patient until in his eighties. On campus he was never seen in anything heavier than a raincoat, though it was reported that he owned an overcoat. After retirement in 1953 he was allowed to keep his cluttered office in East Duke, where he continued to research and write and to hold forth on the topics of the day. In more than one emergency he went back to the classroom for a time. On the fiftieth convocation of the university, he was awarded in absentia the honorary degree of doctor of letters. A busy man but never in a hurry, he died at age ninety-one, quietly, almost willingly, as if he knew he had finished the course. He was buried in the New Maplewood Cemetery, Durham, beside his wife who died in 1968.