See also: Harriet Ann Jacobs from NCpedia Student Collection

February 11, 1813 [or 1815] - March 7, 1897

Harriet Jacobs, writer and abolitionist, was born enslaved in Edenton. It is probable that her father was Daniel, an enslaved and highly skilled carpenter and "old and faithful servant" of Dr. Andrew Knox of Pasquotank County. Her mother Delilah was enslaved by the tavernkeeper John Horniblow. She had one brother, John S. Jacobs, who was younger than herself. Her grandmother, "Yellow" Molly Horniblow, was freed in 1828 and purchased a home in Edenton where she worked as a baker. Jacobs had no formal education, but was taught to read and write by her enslaver's wife, Margaret Horniblow.

Publication of Jacobs's pseudonymous slave narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, established Harriet Jacobs as an African-American activist and writer. Her book was republished in England the following year as The Deeper Wrong: Or, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself. Incidents is unique among nineteenth-century American autobiographies, as it is likely the only slave narrative to focus on sexual oppression alongside oppression of race and condition. It is a first-person account of an enslaved woman's struggle as a mother and against her oppression a sexual object. Its avowed purpose was to enlist American women in the struggle against slavery and racism, and it was only after great difficulty that Jacobs published it with the aid of her editor, abolitionist Lydia Maria Child.

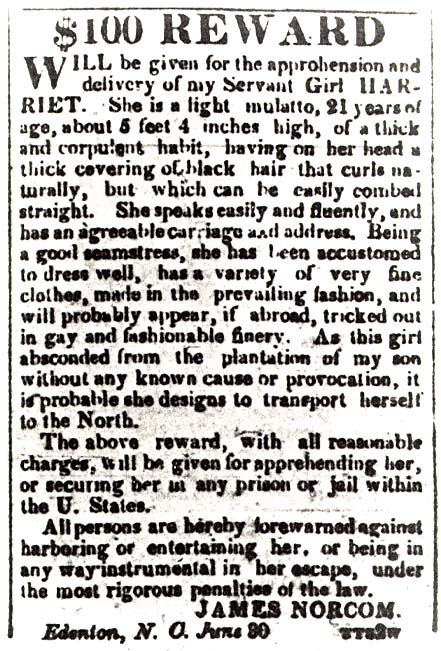

Jacobs composed her autobiography between 1853 and 1858 using the pseudonym "Linda Brent" and fictitious names for others as well. In Incidents, she writes that she was orphaned when a child, and then, following the death of Margaret Horniblow in 1825, the young Harriet Jacobs was sent to a licentious enslaver, Dr. James Norcom, referred to as "Dr. Flint" in Jacob's narrative. Norcom subjected her to unrelenting sexual harassment. In her teens she had two children with another white man, referred to as "Mr. Sands" in the book but likely Samuel Tredwell Sawyer in reality. When her jealous enslaver threatened her with concubinage, she ran away. With the help of sympathetic black and white neighbors, she was sheltered by her family and remained hidden for years in the home of her grandmother "Aunt Martha," a freed black woman. During this period the father of her children, who had purchased them from their enslaver, allowed them to live with her grandmother. Although he later took their daughter to a free state, he did not make good on his promise to emancipate the children.

About 1842, Harriet Jacobs finally escaped to the North, contacted her daughter "Ellen" (Louisa Matilda Jacobs), was joined by her son "Benjamin" (Joseph Jacobs), and found work in New York City as a nursemaid for "Mrs. Bruce" (Mrs. N. P. Willis). In 1849 she moved with her brother "William" to Rochester, N.Y., where both became members of an active group of reformers. Jacobs made a confidante of feminist-abolitionist Quaker Amy Post, who urged her to write the story of her life to aid the antislavery cause.

Jacobs corresponded with fellow abolitionists such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and William C. Nell before her book was published in the early months of 1861. Jacobs traveled to various northern cities, attempting to swell sentiment for emancipation by publicizing and circulating Incidents. During the Civil War, she moved to Washington, D.C., to nurse black troops. Then, with her daughter, she followed the Union armies south.

Well known among reformers as "Linda" because of her book, Jacobs embarked upon a career as a relief worker, making herself a link between the philanthropists of the North and the freedpeople of the South. In 1863 she was at Alexandria, Va., employed by the Quakers of Philadelphia to work among the "Colored Refugees"; in 1865 she was at Savannah, Ga., sent on a similar mission by New York Quakers; in 1868 she was in England soliciting funds for a home for the orphans and the aged among the Savannah freedpeople. The letters Jacobs composed throughout these years and published in the reformers' newspapers comprise an extraordinary series of first-person reports on relief work among the freedpeople.

Little is known of her later years in Cambridge, Mass., and in Washington, D.C., where she died. Jacobs was eulogized as "a woman of strong individuality and marked character" by the Reverend Francis Grimke, a black minister and author who had also been enslaved. She was buried at Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass.