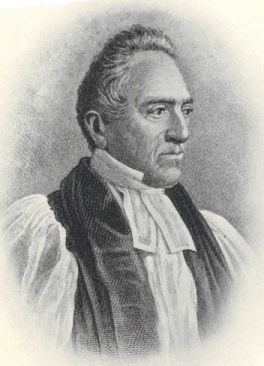

1797–14 Oct. 1867

Levi Silliman Ives, second Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of North Carolina, was born in Connecticut, the son of Levi and Fanny Silliman Ives. Though reared as a Presbyterian, he converted to the Episcopal church in his early twenties, was graduated from the General Theological Seminary in New York, and was ordained deacon in 1822 and priest in 1823. Until his election as bishop in 1832, Ives served various churches in Batavia, N.Y.; Philadelphia and Lancaster, Pa.; and New York City.

Ives had entered the ministry under the auspices of Bishop John Henry Hobart of New York, marrying his daughter Rebecca in 1825. No children of the marriage survived childhood.

Ives was early and consistently identified with the High Church wing of the Episcopal church, of which Bishop Hobart was the acknowledged leader and power broker. This movement was distinguished not so much for any tendencies towards "Romanism," but for accenting differences between it and Protestantism—its emphasis on the centrality of the sacraments, indispensability of the episcopate descending from the Apostles, rejection of theological liberalism and rationalism, rejection of emotionalism and revivalism, wariness of any cooperation with Protestants, and insistence on strict obedience to distinctive Episcopalian traditions and to Prayer Book directives. All of these emphases confined the High Churchmen to a narrow circle of ecclesiastics who, rejoicing in the church's historical catholic past, feared Roman Catholicism as theologically and morally corrupt and Protestantism as hopelessly parochial and volunteeristic.

In 1832 the Diocese of North Carolina was one of the High Church dioceses of the time, and for many years Ives's views and those of the diocese coincided. Lay delegates to the church's General Convention invariably voted with him on issues with High Churchmanship overtones. Ives's episcopate was largely successful for many years because he was able to increase the number of parishes and clergy. In his early years, the diocese at Ives's urging founded a diocesan classical school in Raleigh in hopes that the faculty could be composed of ministerial students who themselves would constitute a small diocesan seminary, but the school closed in 1839 due to inadequate funding and an overly optimistic building project.

Ives's views on slavery were unexceptional. He urged Episcopalians to make provision for the church's ministry to slaves without speaking against slavery as such.

In the 1840s the Tractarian movement in England (also called the Oxford movement and the Puseyite movement) shifted the emphasis of High Churchmanship away from its previous rejection of Roman Catholicism. Some writers seriously maintained that proper High Churchmanship required the reintroduction in Anglicanism of practices, rituals, and theological ideas which they felt had too thoughtlessly and hastily been discarded during the English Reformation. Ives, along with other American bishops, was an early supporter of the English writers who, he felt, deserved a considerate reading. Vociferous opposition from American Low Churchmen, however, caused the movement in some quarters to be branded as theologically dangerous; it seemed to them to blur important distinctions between Anglicanism and Roman Catholicism. In response, many High Churchmen were forced to make their public approbation of Tractarian proposals more circumspect and guarded.

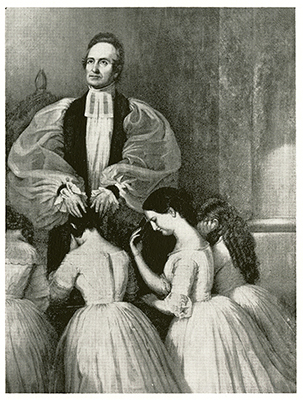

In 1847, two factors caused Ives to be party to the founding of the first monastic community in Anglicanism since the Reformation: the financial impossibility of his paying salaries to clergy for a western North Carolina mission station at Valle Crucis, and the application to him of several recent seminary graduates of thoroughgoing Tractarian persuasions who wished to institutionalize themselves as a monastic order. The evidence suggests that Ives consented to the founding of the order more than he actually instigated it, though it is clear that he personally felt that Anglicanism should be broad enough to tolerate a reformed monasticism. Unfortunately for Ives, various ritualist indiscretions on the part of the monastics became public knowledge just at the time when Low Church outcry against the Tractarian movement peaked, and Ives reluctantly dissolved the order with assurances to the diocese that nothing non-Episcopal had ever been intended. At the same time, he had been preaching a series of sermons to the effect that private auricular confession was at least permissible in Anglicanism and perhaps even desirable—a practice that Low Churchmen of the time especially abhorred as puerile and subject to moral abuse. When Ives announced to several diocesan conventions that he was a "true Episcopalian," therefore, he meant that the practices he had espoused were, in his judgment, compatible with the Episcopal church. Low Churchmen, on the other hand, tended to hear his remarks as retractions and recantations when they were not intended as such.

A pamphlet warfare was carried on throughout 1849–51 between Ives and various High Churchmen and Low Churchmen alike, with Ives maintaining that as bishop he was not canonically subject to being judged theologically by a diocesan convention, and his detractors writing that even a bishop was not immune to proper correction from a lowly layman. By 1851, Ives seems to have become convinced that the Tractarian practices that he wished reintroduced were uncanonical and illegal in the Episcopal church, however desirable they might be abstractly considered, and he made a deliberate effort to dissociate himself from them. He later wrote, however, that in that time of silence he was plagued by the feeling that he had betrayed some essential catholicisms and by the fear that a church that so rigidly denied catholic truths could hardly be catholic itself.

In August 1852 Ives and his wife left North Carolina for an extended trip to Europe, with the very private intention of examining the Roman church in Rome itself. In December, while in Rome, Ives became a Roman Catholic and submitted his resignation as bishop to the Episcopal church.

His letter of resignation did not arrive in the United States until February 1853, dating his conversion in December, but for the previous two months Roman Catholic newspapers had been printing unsubstantiated accounts of an abjuration in New York in October 1852. When the Catholic papers failed to print corrections or clarifications, Protestants tended to conclude that Ives was either dishonest (he had offered to return, prorated, his salary as of 22 December) or had a mental illness (mental illness had been suggested by various Low Churchmen as early as 1849 to explain as charitably as possible Ives's solitary deviations from Episcopal traditions).

Surviving evidence indicates periods of instability in Ives, and the tensions of living in a self-imposed silence to quiet his Roman leanings were agonizing, but mental derangement was a convenient rationale for Episcopalians to explain and accept Ives's resignation. Since then he has been characterized in most Episcopal church historiography as a highly unstable, morbid personality given to excess and overstatement. But in a time of rabid, irrational anti-Catholicism, Ives's espousal of a more inclusive and flexible historical catholicism within Anglicanism received a suspicious and horrified hearing.

Ives returned to the United States in 1854 and was a leading layman in the organization and support of various Roman Catholic charitable institutions. He died at age seventy and was buried in Westchester County, N.Y.