4 Aug. 1808–17 Dec. 1892

Henry Washington Hilliard, lawyer, congressman, diplomat, and author, was born in Fayetteville but shortly after his birth moved with his parents to South Carolina. After graduation in 1826 from South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina), he studied law in the office of William C. Preston in Columbia. He later moved to Athens, Ga., where he continued his legal studies under a Judge Clayton and was admitted to the bar in 1829. From 1831 to 1834 he held the first chair of literature at the University of Alabama but resigned to enter the more lucrative practice of law in Montgomery.

From 1837 to 1839, Hilliard served in the Alabama General Assembly as a member of the Whig party. In the legislature he opposed a resolution supporting the Sub-Treasury and the general ticket plan, which called for a statewide election of congressmen from all districts and was designed to ensure Democratic control of all congressional seats. A delegate to the Whig National Convention in Harrisburg, Pa., in 1839, Hilliard was one of the early supporters of John Tyler for vice-president. Although he favored Henry Clay rather than William Henry Harrison for the presidency, he loyally supported the ticket in the election of 1840. In 1841 he sought election to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Whig, but, even though he won a majority in his own district, he was defeated in the statewide contest required under the general ticket system. In May 1842, after having refused other offers of diplomatic posts, Hilliard was appointed chargé d'affaires to Belgium, a post he held with distinction until June 1844.

In 1845 Hilliard was the first Whig elected to Congress from the Montgomery District and the only Whig congressman elected from Alabama that year. He was reelected in 1847 (without opposition) and in 1849 but declined to run for reelection in 1851. In his maiden speech, for which he was complimented by John Quincy Adams, he supported an aggressive policy in Oregon even at the risk of war with Great Britain. He advocated adequate financing of military forces during the Mexican War. When the Wilmot Proviso was under consideration, he conceded that Congress could legislate for the territories of the United States but insisted that it "must regard the rights of the States" and not "legislate for the benefit of one section at the expense of another."

Although he had reservations about some features of the Compromise of 1850, Hilliard accepted it as a means of reducing sectional differences. When Southern rights associations were formed and threatened secession, he actively supported the cause of compromise, attending a "Union" convention in 1851 at which he was largely responsible for its taking the position that a state had no constitutional right to secede.

Also in 1851 he spoke extensively on behalf of the Whig candidate for the seat Hilliard had held in the House of Representatives, debating William Lowndes Yancey. Throughout his political career, he was the opponent of Yancey and was regarded as the only man in Alabama who could debate him on equal terms. Hilliard was disturbed when adoption of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill brought about repeal of the Missouri Compromise because he feared that its adoption would lead to reawakened prejudice outside the South.

When the national Whig party drifted towards abolitionism, Hilliard joined a number of other former Whig leaders in shifting his support to the American or Know-Nothing party. A presidential elector of the American party in 1856, he made an extensive speaking tour on behalf of Millard Fillmore's candidacy. Soon after the inauguration of James Buchanan, however, he transferred his allegiance to the Democratic party on the ground that conservative forces in the United States should not be divided. At a commercial convention held in Montgomery in 1858, he opposed adoption of any measure that might lead to the reopening of the slave trade.

When the Constitutional Union party nominated John Bell and Edward Everett in 1860, Hilliard left the Democratic party and joined the Union party, which he considered to be the successor to the Whig party of the past, and spoke widely on behalf of the candidates. After the election of Abraham Lincoln, Hilliard opposed secession unless aggressive steps were taken by the national government. In a Montgomery speech that was heard with respect but with little sympathy, he advocated that the rights of Southerners should be asserted within the Union and that all possible remedies should be exhausted before the Union was abandoned.

Hilliard took no part in the measures that resulted in the secession of Alabama nor in the early proceedings of the Confederate government. When Lincoln issued the call for troops to coerce the Southern states, however, he joined the Southern cause. In 1861 he was appointed by President Jefferson Davis as agent of the Confederate government to persuade the state of Tennessee to secede and join the Confederacy. Successful in this assignment, he returned to Alabama and organized "Hilliard's legion," which became part of Bragg's army and was commanded by Hilliard with the rank of brigadier general. In 1862 he resigned from the army and returned to Montgomery, where he resumed the practice of law.

In 1865 he moved to Augusta, Ga., and later to Atlanta. He supported Horace Greeley for president in 1872 and was an unsuccessful candidate for Congress in 1876. In 1877, after considering Hilliard for other diplomatic posts, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him minister to Brazil, where many Southerners had settled after the war in self-imposed exile. During the period of his service in Brazil, the emancipation of more than a million enslaved people was pending. When he was called upon for information about the results of emancipation in the United States, he wrote a letter that helped ensure the success of the movement and made a highly publicized banquet speech. Although questions were raised about the propriety of his action, he became a hero among the supporters of emancipation. In 1881, he returned to Atlanta and lived there until his death.

An author of considerable ability, Hilliard prepared the introduction and notes for a translation of Alesandro Verri's Roman Nights (1850); published Speeches and Addresses (1855), a collection of his speeches; and wrote a novel, De Vane: A Story of Plebeians and Patricians (1865), and his reminiscences (his best work), Politics and Pen Pictures at Home and Abroad (1892).

Although Hilliard was criticized for vacillation during his political career, from his own point of view he was consistent. As a supporter of the Constitution and the Union, he worked for the party that offered him the greatest opportunity to preserve them. An outstanding orator, his debates with Yancey attracted large audiences and nationwide attention. In his early years, he became a Methodist minister and never entirely severed his connection with that profession.

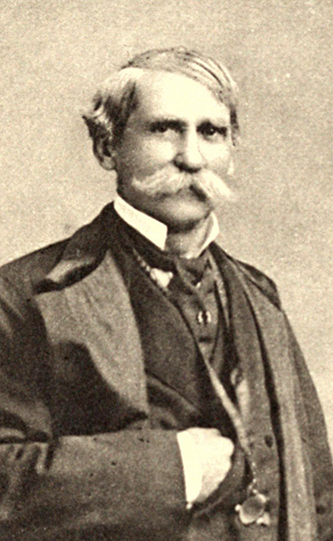

Hilliard was married first to a Miss Bedell and second to a Miss Mays Glascock. After his death in Atlanta, he was buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Montgomery, Ala. His portrait appears as the frontispiece of his Politics and Pen Pictures.