23 Feb. 1818–1 Dec. 1883

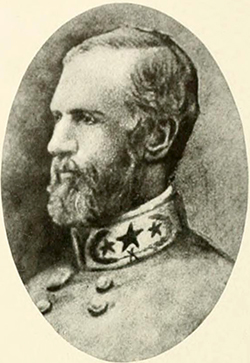

Jeremy Francis Gilmer, military engineer, Confederate major general, and industrialist, was a native of Guilford County, the son of Robert and Anne Forbes Gilmer, both of whom were of Scot-Irish stock. His father was a Revolutionary soldier, farmer, and wheelwright; his older brother was Congressman John A. Gilmer. Jeremy attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where in 1839 he was graduated fourth in a class of thirty-one and commissioned a second lieutenant of engineers.

Gilmer's experiences as a career officer were varied and his success uniform. He was successively assistant professor of engineering at West Point (1839–40), assistant engineer in building Fort Schuyler at New York harbor (1840–44), assistant engineer at Washington, D.C. (1844–46), and chief engineer of the Army of the West during the Mexican War (1846–48). Subsequently he was assigned to duty in Georgia where he superintended the improvement of the Savannah River and the construction of Fort Jackson and Fort Pulaski. He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1845 and to captain in 1853. Afterward he was engaged for five years throughout the South in fortification work and in the improvement of rivers.

In 1858 Captain Gilmer was transferred to the West Coast, where he superintended construction of defenses at the entrance of San Francisco Bay. When word of the firing on Fort Sumter reached California, the local military society, of which Gilmer was a member, was of divided sentiment. Gilmer refused to take the prescribed oath of allegiance to the United States and was relieved of duty. He resigned his commission on 29 June 1861 and planned to return to the South. An attack of rheumatic fever delayed his departure until August, when he sailed with his wife and young son. Warned by fellow officers that possible arrest awaited him in Federal territory, Gilmer left his family and made his way to Georgia via the Ohio Valley and St. Louis, reaching Savannah on 1 Oct. 1861. He was prepared to begin a new career in the Confederate Army.

Gilmer was commissioned major of engineers and posted to the Army of Tennessee as chief engineer on the staff of General Albert Sidney Johnston. Reporting to Johnston at Bowling Green, Ky., on 15 Oct. 1861, he was promptly ordered to supervise defensive preparations at Nashville, Clarksville, Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, and Fort Henry on the Tennessee. Because forts Henry and Donelson were lost in February 1862 and Nashville rendered untenable, Gilmer's role in fortifying these crucial Confederate positions is controversial among historians. James Lynn Nichols (Confederate Engineers) contends that Gilmer's plans were well conceived, and that blame for failure to complete all fortifications before Grant's attack lay elsewhere. Thomas Lawrence Connelly (Army of the Heartland, The Army of Tennessee, 1861–1862) characterizes Gilmer as gullible for expecting civilian aid and dilatory in preparing fortifications. Gilmer himself believed that the losses of forts Henry and Donelson had resulted from too few men and guns. On 6-7 Apr. 1862 he was severely wounded at Shiloh, where Albert S. Johnston was killed. On 1 July Gilmer was notified to his promotion to lieutenant colonel (to date from 16 Mar. 1861) and ordered to join Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. He hoped for field service; but Lee, aware of his Shiloh wound and his old rheumatic ailments, placed him in charge of defense construction at Richmond and Petersburg. Gilmer soon was behind a Richmond desk. Promoted to colonel in October 1862, he became chief of the Confederate Engineer Bureau, a post he would hold, despite extended absences from Richmond, until the war ended.

Gilmer proved to be an effective administrator and was especially influential with President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War James A. Seddon. He was instrumental in organizing engineer companies and regiments and urged that they accompany all field armies. He insisted that all engineer activity, both technical and administrative, be regulated by the engineer chain of command and sought to institute this principle in all Confederate armies and departments. In the summer of 1863 Gilmer secured the publication of General Order #90 as a supplement to the pertinent sections of Army Regulations. It outlined the responsibilities and duties of Confederate engineers, who were to engage in reconnaissance, to prepare maps, to locate all defensive positions, to supervise fortification construction, and to plan and execute mining operations as well as river and channel obstructions. These were ambitious aspirations for an engineer bureau that was always confronted by shortages of men and money.

In August 1863 Gilmer was promoted from colonel to major general of engineers. Concerned about Federal activity around Charleston, Secretary Seddon sent Gilmer south to inspect Atlantic defenses. He was placed second in command to Beauregard for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. In this capacity he was involved in improving the defenses of Charleston and Atlanta. Ordered in December 1863 to command at Savannah and later to inspect Confederate defenses of Mobile Bay, Gilmer yearned to return to Richmond so that he might manage bureau affairs more efficiently. Despite distance and poor communication he had, with the assistance of an acting chief, maintained effective control of the engineer bureau. Finally, in June 1864 Gilmer returned to Richmond where he remained. He accompanied the Davis party in the flight from Richmond at the end of the war, having served the Confederacy ably and loyally. He has been described as the outstanding military engineer in Confederate service.

On 18 Dec. 1850, Gilmer married Georgian Louisa Frederika Alexander (1824–95), daughter of Adam Leopold Alexander and his first wife, Sarah Hillhouse Gilbert. After the Civil War, Gilmer settled in Georgia and was for eighteen years (1865–83) president and engineer of the Savannah Gas Light Company. For many years he was also a director of the Central Railroad and Banking Company of Georgia. He was a trustee of the Independent Presbyterian Church. Gilmer was survived by his wife and two children. He was buried in the family vault in Laurel Grove Cemetery, Savannah.