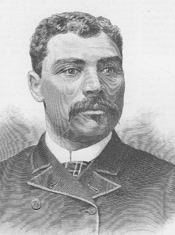

1857 - 1935

Henry Plummer Cheatham, politician, educator, and racial spokesman, was born to a house slave on a plantation near Henderson. Treated with favor by his white father, a prominent planter, Cheatham experienced few of the physical hardships of slavery. After the death of his father, another white man, Robert A. Jenkins, took an interest in him and was largely responsible for providing him the opportunity to attend Shaw University. Although Cheatham studied law, he never became a practicing attorney. After graduating from Shaw in 1882, he served briefly as principal of the black normal school in Plymouth. Both his alma mater and Howard University later conferred honorary degrees upon him.

A dedicated Republican, Cheatham first entered politics in 1884, when he was elected register of deeds in his native Vance County. During his four years in this office, he broadened the circle of friends, both black and white, who later figured prominently in the realization of his political ambitions. He rose rapidly in Republican councils and was elected a delegate to district, state, and national conventions. Chosen as the party's nominee for Congress from the Second Congressional District, the so-called black second, in 1888, he waged a successful campaign against the white Democratic incumbent, Furnifold M. Simmons. At the expiration of his first term in Congress, Cheatham confronted a disorganized Democratic opposition and won reelection with a larger majority than in 1888. But his attempt two years later to retain his seat proved unsuccessful. The emergence of the Populist party and dissension among black voters caused by the question of fusion between Republicans and Populists contributed to his defeat. His 1894 and 1896 efforts to return to Congress as the representative of the black second also failed. As his political star waned, that of his rival and brother-in-law, George H. White, became ascendant.

In the House of Representatives (1889–93), Cheatham was cast as a racial spokesman, especially in the Fifty-second Congress, in which he was the sole black member. Though he championed the cause of black people, he remained aware that his constituency also included white voters. Throughout his two terms he strived to protect the interests of small farmers and home industry—to perform in a manner that would "be best not for one race or the other but for both equally." He sponsored a federal aid-to-education bill, opposed a tax on lard made from cottonseed oil, supported trust regulation and the silver purchase act, and attempted to get the federal government to compensate the depositors of the defunct Freedman's Bank. None of the measures he sponsored were enacted into law, not even his bill for an appropriation to finance a black exhibition at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The latter proposal became embroiled in the struggle over the federal election (force) bill, which he reluctantly endorsed. Even though he failed to win congressional approval of his legislation, he was remarkably successful in obtaining federal appointments for his constituents.

While a congressman, Cheatham not only expanded his land holdings in Vance and Warren counties but also purchased considerable property in Washington in the vicinity of Du Pont circle.

Although Cheatham held no other elective office after his departure from Congress, President William McKinley recognized his services to the party in 1897 by appointing him recorder of deeds, one of the highest offices bestowed upon black men at the time, for the District of Columbia. During his tenure as recorder (1897–1901), he continued to labor in behalf of black people and sought to use his influence with McKinley to protect their interests. A polished orator and loyal supporter of the president, he championed the cause of McKinley Republicanism in speeches throughout the United States during the political campaigns of 1898 and 1900. The rising tide of racial repression in these years prompted black citizens to demand federal action, and when the president failed to take a vigorous stand against lynching and other atrocities, his popularity among blacks declined dramatically. Not only McKinley but also such black appointees as Cheatham became the targets of bitter criticism from the black community. In fact, "Cheatham and Co." was described as a coterie of "white man made" black leaders whose advice to the president had been responsible for his "misguided southern policy." But Cheatham was not without his defenders. James E. Shepard, for example, who served for a time as his secretary and who later became a prominent educator, placed Cheatham in the vanguard of those black men responsible for the progress of the race.

Cheatham belonged to the conservative faction in the black community, and his tactics were similar to those of his friend Booker T. Washington. A man of "moderation, conservatism and well-tempered action," he was diplomatic and circumspect toward whites and was always popular with the old landed people. In dealing with blacks, Cheatham urged them to follow his example, "to be patient, persevering, philosophical, thrifty, self-respecting and far-seeing." The acquisition of property, character, and culture, he consistently maintained, would ultimately "win their place in the equation of civic virtue" and bring about "the triumph of the forces of right." Black critics of Cheatham might quarrel with his penchant for social pacifism and his deferential behavior toward whites, but few disagreed with his ultimate goal—the elimination of racial prejudice and the achievement of first-class citizenship by the nation's black population.

By the time of Cheatham's retirement as recorder of deeds in 1901, the political fate of blacks in North Carolina had been sealed by a succession of legal and extralegal contrivances that virtually nullified the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Unlike George H. White and certain other black political figures who sought to escape the heavy hand of Jim Crowism by settling in the North, Cheatham returned to North Carolina and put into practice his philosophy of racial uplift by assuming the direction of the Colored Orphan Asylum at Oxford, an institution he had helped to establish in the 1880s. When he took over the management of the orphanage in 1907, it was little more than a cluster of shacks. For the remainder of his life he labored in behalf of the institution, expanding and improving its housing and school facilities, brickyard, sawmill, and farm lands. He devoted a substantial portion of his own income to the orphanage and utilized his considerable powers of persuasion in perennial fund-raising campaigns. He not only prevailed upon the state legislature to increase its appropriation but also won for the institution the financial support of the Duke family, especially Benjamin N. Duke. By the end of his twenty-eight-year tenure as superintendent of the orphanage, Cheatham had transformed it from three or four ramshackle wooden structures located on a small farm into an impressive collection of brick buildings surrounded by several hundred acres of prime farm land. Like the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the Colored Orphan Asylum in North Carolina was a monument to the resourcefulness and tenacity of a single individual.

Cheatham was married twice: first to Louise Cherry, the daughter of Henry C. Cherry, a state legislator and influential Republican; and then, following her death in 1899, to Laura Joyner of Branchville, Va. There were three children by the first marriage and two by the second. Less than a month before his seventy-eighth birthday, Cheatham died suddenly at the orphanage.