See also: Ellis, Claiborne Paul “C.P.”

1 July 1935 - 20 June 2016

Ann George Atwater was a lifelong grassroots civil rights activist in Durham, North Carolina. She was born in Hallsboro, Columbus County on July 1, 1935. As a child, she attended the Farmers’ Union School in nearby Whiteville. Her parents, Mr. and Mrs. William Randolph George, both died by the time she was nineteen. At the age of fourteen, she married French Wilson, and soon moved with him and their growing family to Durham, North Carolina in 1953. Her then-husband worked for Venable Tobacco Company and Atwater as a domestic worker. One person for whom she worked was politician and lawyer Henry McKinley "Mickey" Michaux Jr., the first African American Representative from Durham County, and they became life-long associates. Not long after arriving in Durham, her husband moved to Richmond, leaving Atwater to raise their children alone.

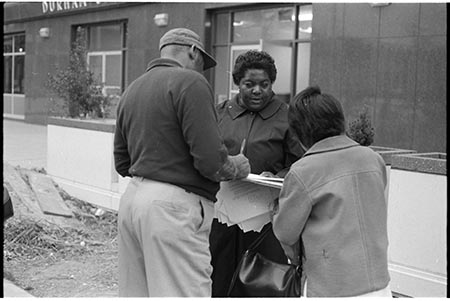

In the mid-1960s, Atwater began her involvement with Operation Breakthrough, the Durham-based organization founded in 1964 to address poverty and inequality. Operation Breakthrough was supported by the North Carolina Fund. Program director Howard Fuller, later head of Malcolm X Liberation University, specifically asked for Atwater to join. Her involvement grew as Social Worker Associate and as a member of their Board of Directors. She took a hands-on community organizing class in 1967, preparing her for the role of Community Action Technician. The activities she led and organized included sit-ins, pickets, and boycotts. Friends and colleagues from the time recalled Atwater as a “natural born leader” and “very wise.”

By 1967, Atwater was also employed by the United Organization for Community Improvement as supervisor of its committee of Neighborhood Workers, plus served as chairman of its Housing Committee. The organization, supported by the North Carolina Fund, helped communities in Durham address issues of food scarcity, voting rights, education, and housing. Her other associations included Head Start, the Low Income Housing Development Corporation, and the Housing Committee of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs. She was elected as local Democratic Party vice president in 1968 and later served with the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People. In addition to being active in the civil rights movement through the decades, Atwater was a lifelong member of the Mount Calvary United Church of Christ, becoming the first female deacon, and served as member of Church Women United and the National Council of Negro Women.

In 1971, Ann Atwater was invited by Durham City Councilman Bill Riddick to co-chair a ten-day “charrette” called “Save Our Schools (S.O.S.).” Federally-funded and sponsored by the state AFL-CIO, the charrette’s mission was to address problems integrating Durham’s schools. It was at this meeting that Atwater met Ku Klux Klan leader Claiborne P. Ellis, assigned as the other chair. What was at first a contentious and combative relationship transformed over the years into a deep, supportive friendship, resulting in Ellis repudiating both the Klan and racism. Their relationship was documented in numerous projects, for example, by Studs Terkel (Race: How Blacks & Whites Think & Feel about the American Obsession), Osha Gray Davidson (The Best of Enemies), and filmmaker Diane Bloom (An Unlikely Friendship).

Atwater started working for the Durham Housing Authority in 1981. Due to an injury on the job, she was forced to retire, receiving medical disability from the Housing Authority in 1991.

Over the years, Atwater received hundreds of awards and official accolades. The Carolina Times newspaper of Durham named her Woman of the Year in 1967. In July 1968, McCall’s published “The Ann Atwater Story.” In 1982, Rosa Parks herself bestowed Atwater the national Women in Community Service (WICS) Rosa Parks Award. Martha Villalobos, WICS national president, said of her nomination, "Ann Atwater was selected from many nominations submitted from across the country because of her extensive voluntary contributions to the poor and the disadvantaged which resulted in a positive influence on the lives of so many people.” In 1997, at the 62nd anniversary of the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, of which Atwater was a member, she was recognized for being a lifelong peacemaker in the Durham community. In 2004, the Durham NAACP awarded her for years of work.

Ann Atwater died June 20, 2016 at age eighty. After spending her life fighting for equal housing and anti-poverty initiatives, news stories about her towards the end of her life show that she was still struggling to pay her bills and relied on donations for some of her own food.

When asked by Chris Gioia in a 1995 interview for the Southern Oral History Program why she was so successful, she responded, “Because I won't take no for an answer, that's why.” Howard Fuller told The News and Observer in 2016, “Ann Atwater is someone who really helped change the history of Durham.” The Durham Civil Rights History mural features Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis in the upper left corner, in a scene working together at the School Charrette Headquarters.