See also: Christ School; Wetmore, Thomas Cogdell

The Struan Estate was a historic property located in Arden, (Buncombe County) North Carolina. Demolished in 1987, the home was one of few properties that featured the Greek Revival architectural style in the mountains of North Carolina. The home was built in 1847 by prominent builder and architect Ephraim Clayton for Alexander Robertson, a wealthy planter and lawyer from Charleston, South Carolina. In the 1800s, the mountains of Asheville attracted prominent South Carolinian families that wished to escape the summer heat and mosquito-borne illnesses like malaria.

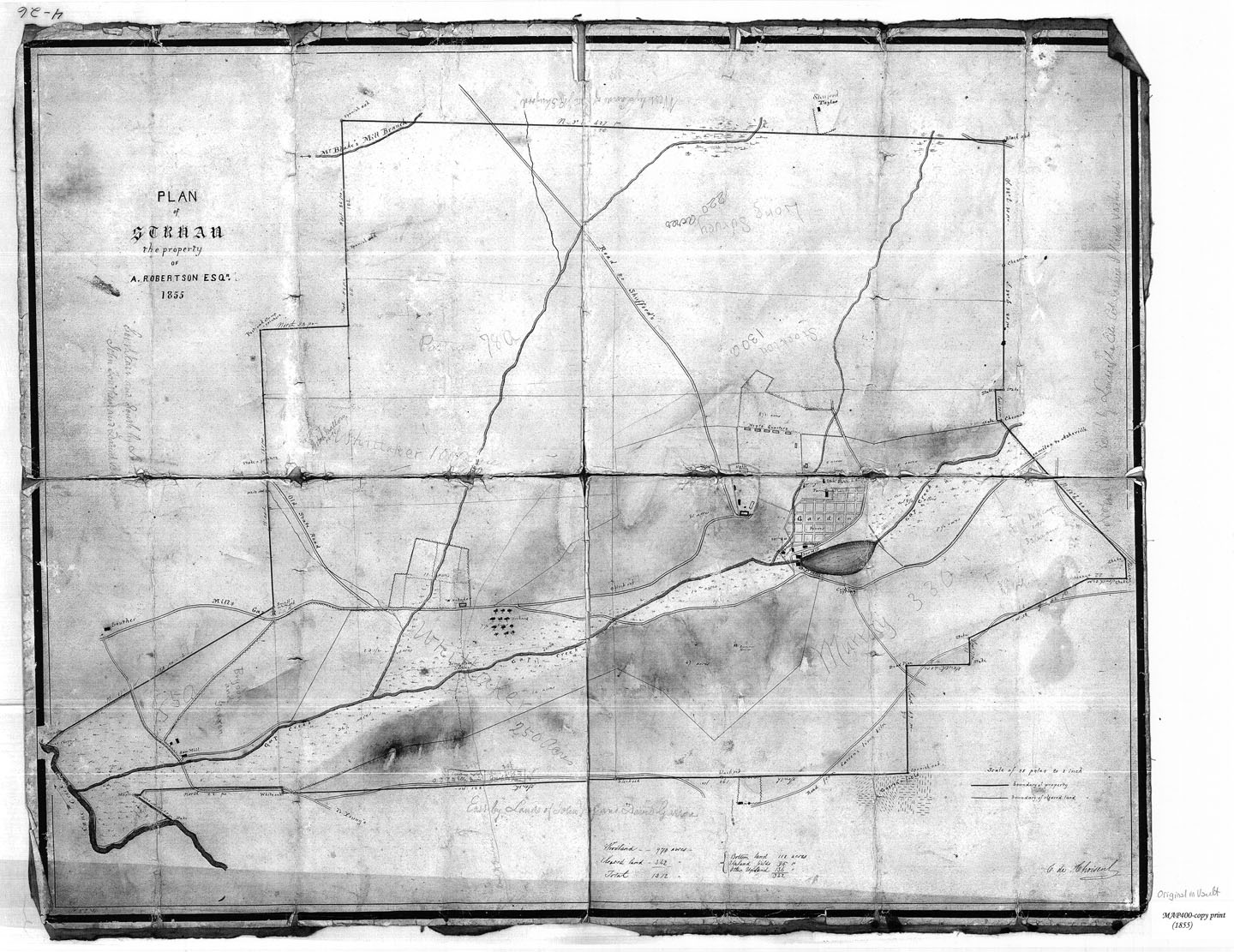

The Struan Estate was not the first house built on its property. In the early summer of 1847, Alexander Robertson and Daniel Blake were riding their horses in the Asheville area when they noticed a gathering of people outside of a stone cottage. The tenant, a postmaster, was being evicted for unpaid taxes. Interested in the property, Robertson paid the taxes and bought the property. The layout of the plot, with a sloping hill down to a stream, interested Robertson, and he decided to build a summer home atop the hill. He called this home Struan, meaning “winding stream,” after his family’s ancestral fortress in the Highlands of Perthshire, Scotland.

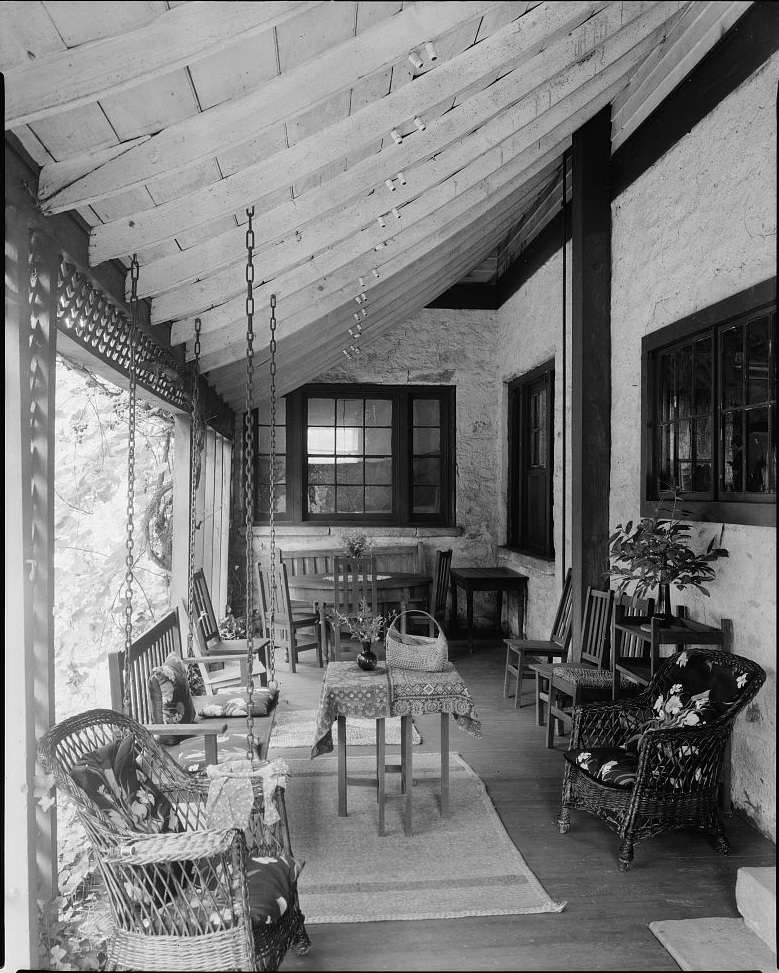

The sixteen-room house was built upon a 1,300 acre lot. It was designed in the Greek Revival style, and faced east to overlook the valley where the stream flowed. The home was the largest Antebellum building in Buncombe County. The home’s white columns enclosed the stone-paved entrance. From the stone-court, large stone steps led up to the front door, which had an ornate silver knocker. The house also featured broad and spacious wings. French doors connected wide verandas to the main home. The verandas opened out to the lawn and flower garden.

Through the main door, a large square hall occupied more than half of the first floor. Robertson held large parties, balls, and weddings in this room. The room was also used as an art gallery for family portraits and other paintings by well-known Antebellum artists. It included works like a large painting of Robertson’s daughter by William Harrison Scarborough (“Susannah Robertson Lyman at the Age of Seven,” 1850). Other notable art pieces in the hall included four George Morland paintings, an original of Marie Antoinette by Adolf Wertmuller, and a portrait of Peter Paul Rubens by Rembrandt.

The house had fourteen foot-high ceilings, and the closet doors in the bedrooms measured five by twelve feet. Robertson had wallpaper brought over from France in 1847. The design of the paper included garlands of pink roses with blue ribbons on a green background. According to Robertson, he loved pink roses. The chintz, carpet, porcelain china from France, and the English cut glass all included pink roses in their designs.

Within the Struan home were many impressive architectural features. The house had two chimneys, each connected to two double-sided fireplaces made of brass and measuring thirty-six inches wide. The first downstairs fireplace was between the sitting room and library, and the second was between the dining room and kitchen. The four upstairs bedrooms shared two fireplaces. They were double-sided, and each fireplace adjoined two bedrooms. Portraits depicting Alexander Roberston and his wife, Penelope Weston Robertson, and a large round mirror hung above the sitting room fireplace. There were decorative vases on the fireplace mantel and two wooden armchairs with plush upholstery faced the fireplace. To the left of the fireplace stood an old grandfather clock and an English sideboard cabinet acquired during the Civil War. According to family history, the sideboard had survived three bombardments during the War of 1812 as well as the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861. It was used to hold and display collections of family silver. Above the sideboard were three paintings, including one of the Struan Estate, created around 1850 in the style of Robert S. Duncanson, a prominent Black Antebellum artist.

The Struan home included many features and details that attested to the Robertson family’s wealth. One such feature of the home was the staircase, which ascended to the third floor without support. Notable accents of the staircase were white treads and hand-carved walnut banisters and newel posts. The door locks, hinges, and knobs were made with silver and brass and marked with a Sheffield, England insignia.

The house included a smoking room, a designated space for occupants and guests to smoke to avoid damaging other rooms in the home. The private library housed about 2,000 books collected by the Robertson family for generations. A large, mahogany table was the centerpiece of the house’s dining room. It had twelve table leaves and could seat up to thirty people. Some of the guests who dined at Struan’s dining table were South Carolina Governors Wade Hampton III and Robert Allston; foreign dignitaries like Joel Poinsett, the Duke de Choiseul of Paris, and Edmund Molyneux of the British Consulate; lawyer James Petigru of Charleston; and Thomas Atkinson, the third Episcopal bishop of North Carolina.

The exterior and gardenscape of the home were also defining features. Pink roses and honeysuckle climbed over the wide verandas. Separate from the Struan home was a kitchen and servant’s hall, and beyond these were the vegetable gardens, riding stables, and quarters for enslaved laborers. A granite grotto in the gardens was flanked by two life-sized white statues of women, called Flora and Fauna, likely brought by Robertson from Charleston. There was also a large oak tree that is still standing today. Down the hill to the stream was a dam made of stone and wood. The water reservoir backed up about 200-300 yards north of the dam. Ten to fifteen feet from the dam, the water reached a depth of about twenty-five feet. Enslaved laborers brought the stone for the dam from nearby Burney Mountain. A grist mill and sawmill stood beside the dam along with the old stone cottage of the evicted postmaster. There was also a blacksmith shop, carpenter shop, farmhouse, spring, and several other structures. Struan was essentially its own working village. This scale of self-sufficiency was very unusual, as much of Buncombe County was rural and underdeveloped at the time.

As a wealthy Antebellum home, the Struan estate used and benefited from the labor of enslaved people. Documents from Buncombe County in 1830 show that Robertson enslaved ten people. An 1855 report, when the Robertson family was well-established at the home, listed seventeen enslaved individuals at Struan. In addition to bringing the people he enslaved from South Carolina to Struan, Alexander Robertson locally rented and purchased at least one enslaved man named Jack around this time. Seventeen enslaved people were listed living on the Struan property on the 1860 census for Buncombe County. A survey map of Struan depicted a “tidy row of five slave quarters,” where enslaved laborers at the estate lived. According to notes about the home, each slave dwelling was a one-room cottage with a blue roof. They likely were constructed from stone and wood and had dirt floors, as this was common for slave dwellings in Antebellum North Carolina. Around five enslaved individuals lived in each dwelling. Enslaved individuals at Struan probably suffered cold temperatures in these uninsulated quarters due to the harsh winter conditions of the mountains of North Carolina.

Robertson relocated the family to Struan when the Civil War began in Charleston in 1861. They brought valuable furniture, silver, and other heirlooms. In 1864, Alexander Robertson’s son was killed in a battle in Virginia. The same year, the Civil War came to Struan. Having been notified of the approach of Union soldiers, the family buried the silver and set all food out in the front of the house. Marks on the wooden floor from the soldiers’ hobnailed boots and a smashed sideboard door were the only damage done to the home by the soldiers. Robertson did not allow the sideboard or flooring to be repaired.

Robertson’s granddaughter, Susan Allan Wetmore, inherited Struan and founded Christ School on the same property in 1900. The goal of the school was to educate poor children from the North Carolina mountains. Due to medical debt incurred from caring for her diabetic son, Susan had to sell many items from Struan in the 1920s. Susan lived at Struan until she died in 1945. Her daughter, Susannah Wetmore Nye, inherited the property and used it as a summer home until her death in 1957. Susannah had no children and thus willed the Struan inheritance to museums and the family of her husband, Douglas Nye. Her beneficiaries received very few of the willed items. In the late 1950s, about 2,000 books, trunks of family papers, and furniture from the Struan home were discovered in an unoccupied and deteriorating house in Asheville. The papers with minimal damage were donated to Christ School while the books and furniture were auctioned off. Information about the Struan Home during its standing is housed the Thomas Cogdell Wetmore Papers Collection (1872-1908) at UNC Chapel Hill. By the 1980s, the Struan home had fallen into disrepair. Sources from the time remarked that it was still surviving but was “in ruins.” Based on accounts from the Christ School, the structure was demolished in 1987 due to its dilapidated and hazardous state.