Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Important Minerals, Gems, and Rocks Mined in North Carolina; Part iii: References

See also: Bechtler Mint; Big Ore Bank; Cabinet of Minerals; Gold Hill Mine; Gold Rush.

A variety of minerals, gems, and rocks have been excavated in North Carolina since the precolonial era. Mining was known to the region's Indians before European settlement, and evidence of mica mining and trade with other tribes may be seen at the Baird Mine in Macon County and the Sink Hole Mine in Mitchell County. It appears that Indians also used talc and soapstone for making utensils. Other resources exploited early were clay and kaolin. The colonial period saw mainly local use of these materials as well as the burning of shell marls for cement and small-scale iron making from the most accessible deposits.

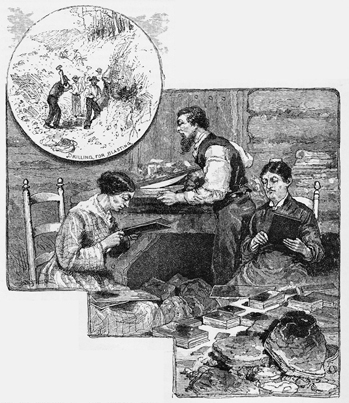

In the nineteenth century there was an abundance of mining activity as the state surveyed its mineral assets. As early as 1822, Professor Denison Olmsted at the University of North Carolina submitted a descriptive list of rocks and minerals to the American Journal of Science, some of which he had collected himself and others that had been sent to him. In 1871 C. E. Jenks began to mine gem corundum in Macon County, but this evolved into the more profitable abrasive business with gemstones an erratic by-product. Around 1874 J. Adlai D. Stephenson of Statesville offered rewards to anyone finding minerals of interest and was the first collector reported to have the then-unknown hiddenite in his collection. Gen. Thomas L. Clingman, William E. Hidden, and George F. Kunz were also active mineral collectors of the late nineteenth century.

North Carolina's small but unique gemstone supply-the state has the greatest variety and quantity of gemstones in the East-became attractive to collectors. From 1881 to 1919 the production of all gemstones, including aquamarines, rhodolite garnets, golden beryl, emeralds and hiddenite, and gem corundum (rubies and sapphires), was a minor but colorful industry. As the twentieth century progressed, lithium and tungsten mines and phosphate deposits were opened. New industrial applications were found, while the market for old reliables such as feldspar and mica, along with new beneficiation techniques, increased their rate of recovery. Gemstones in the late twentieth century remained a factor in the state's economy, with numerous mines open to amateur collectors and annual production averaging about $50,000. Several of these commercial mines, such as the Cherokee Ruby Mine, Cowee Mountain Ruby Mine, and Jackson Hole Mine, were located in Franklin (Macon County), which is also the site of the Franklin Gem and Mineral Museum.