See also: Contrabands; African Americans People in North Carolina - Part III: Emancipation; Juneteenth on ANCHOR

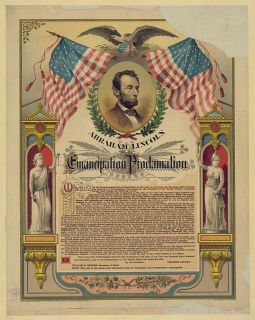

Emancipation of enslaved African American people in the south became official on 1 Jan. 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation freeing people enslaved in areas of armed rebellion against the U.S. government, including North Carolina. Although the Proclamation marked Lincoln's attempt to end slavery, many enslaved people in North Carolina had engaged in actions toward the same end from the outset of the Civil War. African American men constituted a large portion of the Confederate labor force working, often against their will, on the fortifications of Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, as well as along North Carolina's coastal rivers prior to open hostilities between north and south. But this new use of enslaved laborers separated Black men from their families and subjected them to military overseers, both of which alienated many enslaved workers from the Confederacy. As the war progressed, they fled not only military labor but also Confederate impressment and their enslavers' actions to move them away from Union lines. Despite the efforts of North Carolina enslavers, thousands of enslaved people crossed Union lines to freedom.

When Union commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside launched his expedition into northeastern North Carolina in February 1862, he unknowingly provided enslaved people with a new sanctuary. Initially, Burnside hoped not to become involved in the slavery issue, but on 21 March he reported to the U.S. Secretary of War that "it would be utterly impossible if we were so disposed to keep [enslaved people] outside of our lines, as they find their way to us through woods & swamps from every side." The massive influx of freedom-seeking people created tension between Burnside and Edward Stanly, whom Lincoln appointed Military Governor of North Carolina in April 1862. Stanly believed it his duty to protect North Carolina law in order to promote unionism in the state. This conviction led him to disband schools for African American people in New Bern, to return a local Unionist enslaver's young enslaved woman, and to protest the Emancipation Proclamation. Ultimately, it was his government's emancipation policy that prompted Stanly to resign on 15 Jan. 1863 because he feared that it would needlessly lengthen the war.

Perhaps there was some truth in Stanly's protests. Despite Lincoln's cautious path to emancipation, his acceptance of it as a military necessity in July 1862 rattled North Carolinians. Burnside, like other union commanders already inundated with freedom-seeking enslaved people when Lincoln issued the preliminary Proclamation following the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) in September 1862, encountered swelling numbers afterward. The Emancipation Proclamation exacerbated rising class tensions in North Carolina. In the wake of the Confederacy's April 1862 Conscription Act, which exempted one white male per farm which owned twenty or more enslaved people, non-enslavers' commitment to the southern cause waned.

The North Carolina press viewed the preliminary Proclamation as an indication of the Union's intention to abolish slavery and subjugate white men and predicted that southerners would further rally behind the Confederacy. Yet the opposite occurred in North Carolina: class conflict between non-enslavers and enslavers increased, as did desertion from the Confederate armies. After January 1863, yeoman farmers could no longer conceive of sacrifice for an institution in which they possessed only a "casual interest."