See Also: Emancipation

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Life under slavery and the achievements of free Black people; Part iii: Emancipation and the Freedmen's Fight for Civil Rights; Part iv: Segregation and the struggle for equality; Part v: Emerging roles and new challenges; Part vi: References

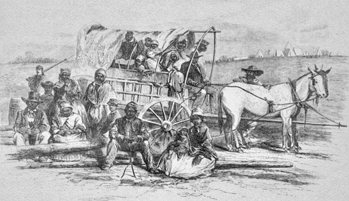

The conditions of African Americans changed dramatically after the outbreak of the Civil War. The Confederates used the labor of enslaved Black people to operate railroads, to construct earthworks and fortifications, and—in the closing days of the conflict—to fight in their army. Many enslaved people defected to Union forces in eastern North Carolina. A sizable number joined the African Brigade, first organized in New Bern, to bear arms for the Federal army. Perhaps as many as 5,000 Black North Carolinians fought for the Union.

With the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, nearly 4 million enslaved people were freed by the end of the war, more than 360,000 of them in North Carolina. Despite their lack of schooling, these African Americans demonstrated a clear vision of what they wanted and a strong determination to get it. Like their fellow citizens, they demanded independence and the opportunity to own their own farms, businesses, and homes, and they were willing to work as hard as necessary to achieve these goals. They also desired education for themselves and their children, making great sacrifices toward this end; a full and rewarding social life, surrounded by family and friends; and protection from physical abuse, intimidation, and discriminatory laws.

The majority of North Carolina’s white population sought to keep African Americans in a subservient position, politically and economically. The state’s 1865 Black code restricted their movements, economic opportunities, and civil rights. Black people were limited in their right to testify in court, received discriminatory penalties for crimes, and could not vote. Planters sought a stable labor force through restrictive contracts, low wages, apprenticeship, physical intimidation, and, in some cases, abuse of the court system. Most Black people worked peacefully but with determination to change attitudes and policies.

Socially, thousands of the state’s African Americans reunited their families and married the person with whom they had previously cohabited. They deserted white churches and formed new ones, either affiliating with white northern or African Methodist Episcopal churches. Black churches quickly became the center not only for religious worship but also for educational instruction and community pride. Black people also organized a rich cultural life, forming bands and lodges, sponsoring parades and exhibits, holding balls and dances, and establishing a few newspapers to serve their communities. Moreover, North Carolina’s freedpeople exhibited a ‘‘mania’’ for education. Almost immediately after the war, Black Americans in many areas began to raise money to build schools, buy books, and pay teachers. Within two years, more than 150 schools taught approximately 13,000 Black children.

Freedmen held two statewide conventions (1865 and 1866), in addition to numerous mass meetings throughout the state. At these gatherings, they praised the work of congressional Republicans and the Freedmen’s Bureau and called for full civil and political rights. They also pressed for more economic equality, complaining of physical abuse and intimidation, nonpayment of wages, mistreatment by their former masters, low pay, and the unavailability of land for them to purchase. Black people established the Freedmen’s Educational Association of North Carolina to promote Black education and an Equal Rights League to advance their civil rights. Many of the state’s traditionally Black colleges were established in this era. Freedmen also organized one of the South’s most successful Union Leagues, which became the basis for political education once Black suffrage was instituted. They protested abuse of the apprenticeship system, whereby children were removed from their parents and apprenticed to their former owners. Taking their grievances to the Freedmen’s Bureau and to state courts, they finally won a victory in 1867, when the North Carolina Supreme Court voided the apprenticeship contracts of Harriet and Eliza Ambrose to Daniel L. Russell and delivered a strong censure of those who violated due process of law.

When Black men gained the vote in 1867, their political activity increased in North Carolina. Between 1876 and 1894, 52 African Americans were sent to the Lower House of the General Assembly. The Second Congressional District, known as the ‘‘Black Second,’’ served as a political stronghold between 1872 and 1900, electing such representatives as John A. Hyman, the first African American in North Carolina to sit in the U.S. Congress; James E. O’Hara, the state’s second Black congressman; and George H. White, the last former enslaved person to serve in Congress.

Life for Black North Carolinians following Reconstruction appeared to be liberal by late nineteenth-century standards. After the passage of the national Civil Rights Act of 1875, many African Americans exercised their new freedom in railroad cars, steamboats, hotels, theaters, and other public venues. Their political gains came at great cost, however, and were muted by the return of Democrats to power in 1876. The newfound freedoms enjoyed by Black citizens fueled a brutal backlash by angry whites. North Carolina saw the eruption of widespread violence by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, whose purpose was to terrorize Black people and diminish their newly won political rights. When the Republican and Populist Parties collaborated in the mid-1890s to again oust the Democrats, their ‘‘Fusion’’ government yielded Black people more funds for education and direct election of local officials, as well as a wealth-based tax system.

In response, brutal white supremacy campaigns in 1898 and 1900 enabled the Democratic Party—through fraud, intimidation, violence, and racist rhetoric—to return to power in North Carolina. The Democrats then set out to prevent any future challenges to white supremacy, amove grounded in African American disfranchisement. Building on the ‘‘separate but equal’’ doctrine established in the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, North Carolina Democrats in 1899 passed Jim Crow laws instituting a system of legal segregation. The next year, white citizens approved a state constitutional amendment requiring all voters to pay a poll tax and pass a literacy test unless an ancestor had voted in an election prior to 1 Jan. 1867. Intended to disfranchise the African American population, the amendment succeeded in eliminating Black North Carolinians from traditional politics.