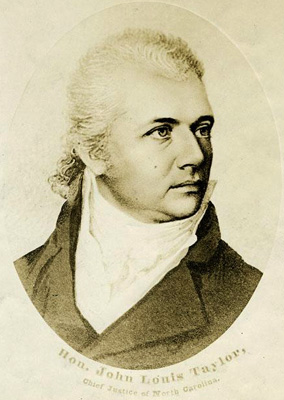

The Supreme Court of North Carolina is a seven-member tribunal occupying the apex of the state's General Court of Justice and possessing appellate jurisdiction to review the decisions of lower courts and administrative boards within the executive branch of state government. Acting on a bill introduced by William Gaston of New Bern, the General Assembly in November 1818 created the separate supreme court contemplated by the Constitution of 1776, which empowered the legislature to appoint "Judges of the Supreme Courts of Law and Equity" and "Judges of Admiralty." Composed of a chief justice and two "judges," the new tribunal was commissioned to exercise exclusive appellate jurisdiction over questions of law and equity arising in the superior courts. The first meeting of the court took place on 1 Jan. 1819, and soon the court began holding two sittings, or "terms," a year. The governor, with the assistance and advice of the Council of State, temporarily filled vacancies on the supreme court until the end of the next session of the General Assembly.

The legislature's creation of an independent appellate judiciary ran counter to the reforming democratic spirit of Jacksonian North Carolina. From the beginning, opponents objected to the judges' salaries, which at $2,500 per year were considered extravagant (at the time the governor annually received only $2,000). The judges' right to "hold office during good behavior," a virtual guarantee of life tenure, angered reformers who regarded the court as an elitist institution too far removed from the people. The growing population of the western counties, naturally given to criticizing an unresponsive, distant state government dominated by eastern planters, protested the long journeys their lawyers had to undertake to argue cases from the overburdened western circuits before the supreme court. To their voices were added those of superior court judges, who resented being reversed on appeal. Throughout the 1820s regular attacks were leveled at the North Carolina Supreme Court by legislators who believed that the chief justice and the two judges should be elected by popular vote.

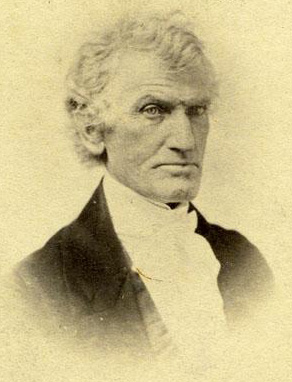

The 1829 election to the bench of former superior court judge and State Bank of North Carolina president Thomas Ruffin effectively ensured the supreme court's survival, as he single-handedly transformed the common law of the state into an instrument of economic change. Ruffin's writings on the issue of eminent domain-the right of the state to seize private property for the public good-paved the way for the expansion of railroads into North Carolina, enabling the state to embrace the Industrial Revolution. Ruffin's opinions on various subjects were cited as persuasive authority by appellate tribunals nationwide.

The supreme court survived the Civil War, during which its docket was greatly diminished under the leadership of Chief Justice Richmond Pearson. Four major reforms befell the court as a result of North Carolina's adoption of a new constitution in 1868. First, in an extensive revision of the judicial article, the court became a "constitutional" tribunal that owed its existence to the fundamental law of the state rather than to legislative enactment. Second, the number of judges was increased from three to five, with the chief justice retaining his title and his brethren receiving the appellation "associate justices." Third, the justices, including the chief justice, were to be elected by the people for eight-year terms. In the event of a vacancy, the governor was to appoint a substitute to sit until after the next general election of members of the General Assembly.

The twentieth century called upon the supreme court justices to decide a variety of cases related to the responsibilities and limitations of a growing state bureaucracy. Many of these governmental controversies had at their root questions regarding separation of powers: the principle that the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government should be, in the words of the North Carolina Declaration of Rights, "forever separate and distinct." At the same time the court continued to handle modifications to common law, fashioning new doctrines to meet the demands of a rapidly changing state. The 1980s and 1990s occasionally saw the justices interpret the state constitution as a more capacious vessel of individual rights than its federal counterpart.

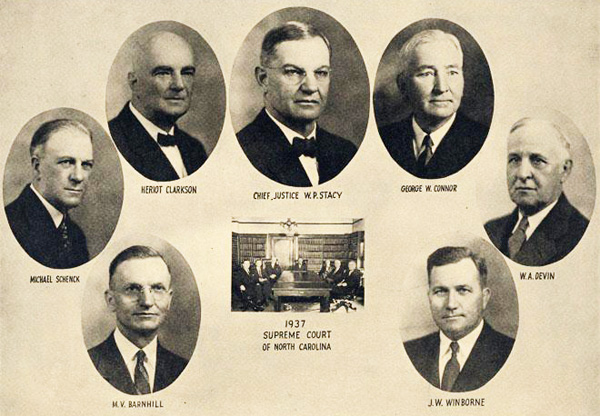

The primary function of the modern Supreme Court of North Carolina is to decide questions of law arising in the lower courts and before state administrative agencies. The justices spend most of their time outside the courtroom reading written case records, studying briefs prepared by lawyers, researching applicable law, and writing opinions detailing the reasoning on which the court's determinations are based. The General Assembly in 1937 passed legislation raising the number of justices to seven. The concurrence of four justices generally is required for a decision; each of the seven justices participates in every case except in unusual situations where a justice may feel compelled to recuse, or withdraw, from sitting.

In addition to cases awaiting decision, the justices consider numerous petitions in which a party seeks to bring a case before the court for adjudication. Although most of these requests are denied, the justices read hundreds of records and briefs and spend many hours in conference deliberating their merits. Each justice writes approximately 250 printed pages of opinions every year. These opinions are published in the North Carolina Reports and in several unofficial publications; they may be found in major law libraries throughout the world.