John Lawson

Explorer and Naturalist

by Dr. Vincent Bellis

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 2007.

Original title, "John Lawson’s North Carolina."

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: John Lawson from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography.

When John Lawson was a teen-ager in the final decade of the 1600s, England was becoming the “ruler of the seas.” His hometown of London was a world center of trade and learning. John’s great-uncle had been a vice admiral in the English navy. His father was a prosperous doctor with social connections among leading scientists, ships’ physicians, and explorers, people that he often invited to his home.

John’s mother died when he was sixteen, and he began attending Gresham College near his home. Unlike most colleges, which emphasized religious studies and the law, Gresham offered classes in mathematics and natural science. The college also was home to England’s most prestigious organization of scientists, the Royal Society. John had many chances to attend lectures by these learned men. Perhaps he would have heard of new herbal cures recently discovered in the Americas. Jesuit’s bark from Peru could reduce the symptoms of malaria. Bark from a North American tree called by its Indian name, sassafras, made a pleasant tea that calmed the stomach and stopped headaches.

By the time he was a young man, John Lawson was ready to set out on his own. He wanted to make money and may have dreamed of being elected to the Royal Society. He probably had no idea that plants would become an important part of his New World adventures.

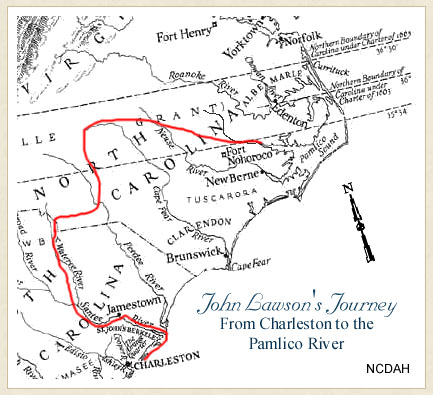

In 1700, when Lawson was twenty-five, he boarded a ship bound for what is now Charleston, South Carolina, arriving there near the end of the year. On December 28, 1700, the day after he turned twenty-six, he set out with several Virginia traders and their American Indian guides. This journey of exploration through the little-known backcountry of Carolina took him near the sites of modern cities like Charlotte, Hillsborough, Raleigh, and Greenville. Lawson ended his travels at the home of Richard Smith near Washington, North Carolina, where he was “well received by the inhabitants, and pleas’d with the goodness of the country.”

In 1700, when Lawson was twenty-five, he boarded a ship bound for what is now Charleston, South Carolina, arriving there near the end of the year. On December 28, 1700, the day after he turned twenty-six, he set out with several Virginia traders and their American Indian guides. This journey of exploration through the little-known backcountry of Carolina took him near the sites of modern cities like Charlotte, Hillsborough, Raleigh, and Greenville. Lawson ended his travels at the home of Richard Smith near Washington, North Carolina, where he was “well received by the inhabitants, and pleas’d with the goodness of the country.”

Lawson became a founder of Bath, the first town in North Carolina, and a business partner of Smith and his daughter, Hannah. The Smiths were active in the deerskin trade and land development. Lawson used his talents in math as a land surveyor, and in that job, he traveled widely. Attracting investors to the area would help him financially. So in 1708 he returned to England for a year to publish a book describing and promoting Carolina. By that time, Lawson and Hannah Smith were the parents of a daughter, Isabella.

Back in London, Lawson met James Petiver—an apothecary known for his vast collection of natural history specimens. Petiver was one of many rich English gentlemen who competed with one another to show off or exchange exotic things brought from far away lands by English trading vessels. These men impressed people by showing rare butterflies or growing tropical plants in their gardens, just as some people today show off their yachts, fancy cars, and homes.

Years before, when he had first traveled to the New World, Lawson had been among about eighty people who wrote Petiver in response to his advertisement seeking plant and animal samples. There is no evidence that Petiver—a great collector of everything from seashells to ancient coins and Greek and Roman sculpture—followed up. But when they met in person, Petiver asked Lawson to send him specimens of dried plants and animal skins after he returned to the New World. Petiver also supplied Lawson with apothecary and botanical materials. Lawson had asked for varieties of grape vines and stone fruits to take back to North Carolina, as well as information on making wine and distilling spirits. He wanted to grow cork trees and requested medicines to treat sick immigrants.

Lawson did return to North Carolina in the spring of 1710, leading several hundred German colonists who were to occupy land on the Neuse River that he had bought and resold to Baron Christoph von Graffenried. This site would become North Carolina’s second town, New Bern.

Although not a trained botanist, Lawson fulfilled his promise to Petiver. He sent packets of dried plants to him in 1710 and in 1711. The plants reached London some three months after being shipped out of Norfolk, Virginia. Lawson’s plants were apparently stacked among those of other collectors and were not well cared for. There is a lot of evidence that labels were misplaced, and there was insect and water damage. These dried plants eventually found their way to the Natural History Museum (British Museum), where they can be viewed today. Images of those specimens and additional information about Lawson may be found at the East Carolina University's Joyner Library's John Lawson Digital Exhibit. The collection consists of just over three hundred specimens, including 108 species that have been identified.

The plants that Lawson collected and the notes he made about them, including dates and places, can tell us a lot of important things about what he was doing, and where he traveled, in the months before his death.

In April 1710 two ships containing Lawson and his German colonists arrived off the Virginia capes at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Lawson’s ship made it in to port. A French privateer captured the other ship and held it for nearly a month before releasing it. Lawson began collecting plants even as he led the exhausted colonists south toward New Bern. On May 10, 1710, he collected a huckleberry and wrote this note: “The largest huckleberry... green berries on the stem... we’ve gotten in Norfolk County in Virginia.” The travelers had gotten as far as Dare County on May 29. Lawson’s note from that date on a plant he collected reads, “A species of Willow gotten on the Sand Banks near Ranoak Island.” Within the week, the party had reached New Bern, because Lawson there collected a specimen that he labeled “Chickapin in flower, June the 4th, 1710.” He had collected dozens of plant specimens by the end of the month. These were packaged and sent to England in July 1710.

Also in 1710 Lawson made several trips from New Bern to Williamsburg, Virginia. He was helping the Royal Commission that was trying to set the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. Lawson made the trips in a small boat because land travel was unreliable and required going through territory controlled by the Tuscarora Indians. He arrived late for his appointments with the commission. He must have recognized that a safe land route between North Carolina’s more settled Albemarle region and the new colony in New Bern was badly needed.

Also in 1710 Lawson made several trips from New Bern to Williamsburg, Virginia. He was helping the Royal Commission that was trying to set the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. Lawson made the trips in a small boat because land travel was unreliable and required going through territory controlled by the Tuscarora Indians. He arrived late for his appointments with the commission. He must have recognized that a safe land route between North Carolina’s more settled Albemarle region and the new colony in New Bern was badly needed.

The winter of 1711 found Lawson back in New Bern, planning a more-detailed survey of the water route between the Neuse River and Albemarle Sound. He left New Bern during the last week of January. On January 29 he collected a plant “spontaneous of Carolina growing on a Fork of Neus River and in other places... had from flowers, like drops of blood a few... sweet herb.” Two days later, he stopped at William Hancock’s “on the south side on Neus Rv.” There, he collected specimens of American olive, which he described as “a pritty [sic] tree growing on a sandy point by the water side.” On February 8 he described a holly having leaves “more prickly” than English holly and, “this pleasantest Evergreen growing amongst Cedar, Holly & many other evergreens... gotten off the mouth of Broad Creek on the North side.”

We can use Lawson’s notes to trace his route as he navigated the shoreline along the south side of the Pamlico and Albemarle Peninsula, Croatan Sound, and Albemarle Sound. He arrived around the end of April 1711 at the home of Colonel Thomas Pollock, near the mouth of the Chowan River. Between February and April he collected plants at Long Shoal River, Croatan Woods, Little River, and Salmon Creek. Lawson was familiar with the common names of many plants, as well as the Indian names of some unique to North Carolina. His notes include references to dogwood, sand willow, golden rod, sourwood, wax gatherer’s plant, maple, cherry, gallberry, willow oak, hickory, and spice tree, and to Indian names like chickapin, pau pau, and yaupon.

The plants Lawson gathered during this trip were sent to England from Virginia in July. By August 1711, he was back in New Bern. His explorations had not discovered a faster or safer way to Virginia or Albemarle. He now begged von Graffenried to make a trip up the Neuse River in search of a land route north. In early September the two men— accompanied by two of the baron’s servants—headed up the Neuse River by canoe. The group had failed to ask the local Tuscarora for permission to cross their land. The Indians captured them. They released the others but killed Lawson.

Lawson’s last letter to Petiver was written in July 1711 from Virginia. It may have accompanied the dried plants collected that spring. Lawson writes Petiver that he has more specimens in New Bern. Petiver got the letter in London on October 20, 1711, almost exactly a month after Lawson’s death.

At the time of this article’s publication, Dr. Vincent Bellis was a retired professor of biology from East Carolina University. He has read Lawson’s A New Voyage to Carolina many times and continues to find new information about early plants, animals, and habitats in eastern North Carolina.

Podcast credit:

Davis, B.J. 2010. "John Lawson's exploration of the Carolinas: a conversation with Jeanne Marie Warzeski, North Carolina Museum of History." Accessible at: http://digital-library.ncdcr.gov/u?/p249901coll22,30492

Image credits:

Map of Lawson's journey from Charleston to the Pamlico River. History Bath, North Carolina Historic Sites: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/bath/lawson.htm

A sketch of John Lawson’s capture by the Tuscarora. Image courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives. Call no. N.70.10.61

References and additional resources:

Brooks, Baylus C. “John Lawson’s Indian Town on Hatteras Island, North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 91, no. 2 (2014): 171–207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23719093.

Hairr, John. “John Lawson’s Observations on the Animals of Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 3 (2011): 312–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523634.

Latham, Eva C., and Patricia M. Samford. “Naturalist, Explorer, and Town Father—John Lawson and Bath.” The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 3 (2011): 250–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523630.

Mathewes, Perry. “John Lawson the Naturalist.” The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 3 (2011): 333–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523635.

John Lawson Digital Exhibit. Joyner Library, East Carolina University. Online at: http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/exhibits/lawson/index.html

LearnNC resources about John Lawson.

North Carolina Digital Collections resources about John Lawson (Government & Heritage Library and NC State Archives)

Resources in libraries [via WorldCat]

1 January 2007 | Bellis, Vincent