Religious Life in Antebellum North Carolina

by Gary Freeze

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 1996.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Protestant Christianity was central to the lives of North Carolinians in the antebellum period. Many of these citizens had become Christian believers as teenagers during the Great Revival, then grew up and built churches in every part of the state. Most churchgoers in antebellum North Carolina were Baptist or Methodist. Each of these two denominations had at least one church in each county by 1850.

Protestant Christianity was central to the lives of North Carolinians in the antebellum period. Many of these citizens had become Christian believers as teenagers during the Great Revival, then grew up and built churches in every part of the state. Most churchgoers in antebellum North Carolina were Baptist or Methodist. Each of these two denominations had at least one church in each county by 1850.

In some areas, preachers were in such short supply (as was cash to pay them) at this time that congregations often shared ministers and could not hold worship services every Sunday. Some folks worshipped once or twice a month at their own church, then visited other community congregations on the other Sundays. Few choirs sang. Instead, a song leader "lined" the music by singing the first line aloud to teach the tune. The congregation then sang immediately afterward, following his example. Besides singing, antebellum church services required a lot of sitting and listening, since sermons could sometimes last more than an hour. Baptist and Methodist sermons often used simple messages to invoke the fear of an unheavenly afterlife. Presbyterian and Episcopal sermons, on the other hand, usually used more complex theological themes to attack the sins of adult life.

So why were church and religion so important at the time?

The Church as a Social Organization

Attending church was a social event as well as a worship activity. Church buildings were gathering places where men and women could meet before services began. They shared gossip, visited, and learned news of the day. Children and young people played, and adolescents and young adults courted. But everyone stayed in sight because when the minister quit shaking hands and disappeared into the building, it was time for all to assemble inside.

A highlight for many Methodists and some Baptists was the annual camp meeting. Each summer, while crops were laying in, waiting to be harvested, families gathered at the campgrounds for a long weekend of worship. They stayed in small huts, called tents, and went to services three times a day. They visited each other, ate together, and read from their Bibles and prayer books between sessions. Camp meetings were very popular. The largest in the state, Rock Springs in Lincoln County, attracted more than ten thousand people each year during the 1840s.

The Church as a Community's Discipline

Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists "disciplined" their members, holding church members accountable, or responsible, for the deeds they did when they were not in church. For example, a man caught swearing in a public place, like the courthouse, might be asked by church leaders to "repent"—to say he was sorry and would cease such behavior. If he refused, he could be "denied fellowship," meaning that he could not participate in important church activities like Communion.

Men and women could also be disciplined by their church for cheating, dancing, or demonstrating drunkenness or immoral sexual conduct. One Methodist in Lincoln County, for example, was accused of picking up a bolt of cloth on the road and failing to return it to its rightful owner. A Baptist member was once brought before his congregation to explain why he had wrongly spent money that belonged to a young orphan.

The Church as a Leader in Education

The Church as a Leader in Education

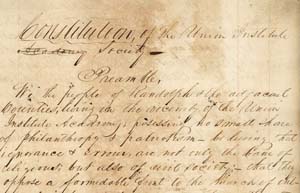

Members of religious groups in North Carolina started a number of private colleges in the state. The earliest were founded in the 1830s and 1840s: Wake Forest by the Baptists (1834), New Garden Boarding School by the Quakers (1837; it later became Guilford College), Davidson by the Presbyterians (1837), and Union Institute by the Methodists (1839; it later became Trinity, and even later Duke). These colleges stressed the teaching of ancient and modern languages, public speaking, and rhetoric. They also taught mathematics and other subjects, but their primary goal was to train young men to become ministers and other church leaders.

By the 1850s, many churches in towns had added Sunday school classes for both children and adults to their Sunday schedules. Subjects included reading and writing as well as Bible study.

References and Additional Resources:

Guide to researching the history of religion in North Carolina. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/study/religion.html

Johnson, Guion Griffis. 1937. Ante-Bellum North Carolina: A social history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/johnson/menu.html

Resources on religion and North Carolina from libraries [via WorldCat]

Image Credits:

Detail of the first page of the Constitution of the Union Institute Society. 1839. From the Duke University Archives. http://library.duke.edu/uarchives/history/histnotes/uiconst1839.html

Dubourg, M. c. 1819. American Methodists proceeding to their camp meeting. Reproduction no. LC-USZC4-3264. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., USA. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/95504484/

Johnston, Frances Benjamin. 1938. Old camp meeting, Denver, Lincoln County, North Carolina. Call no. LC-J7-NC- 2595. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., USA. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/csas200802839/

1 January 1996 | Freeze, Gary