Ruark, Robert (Bobby) Chester, Jr.

29 Dec. 1915–1 July 1965

Robert (Bobby) Chester Ruark, Jr., columnist, satiric essayist, and novelist, was born in Wilmington, the son of Robert Chester, an accountant, and Charlotte Adkins Ruark. His paternal grandparents were Harrison Kelly (Hanson) and Carolina Ruark; his maternal grandparents were "Captain" Hawley Adkins and his wife Lottie. It was Captain Adkins who owned the house at the corner of Lord and Nash streets in Southport where Bobby spent much of his childhood and which he later bought from his grandfather's estate. Adkins also taught the boy to hunt and fish and to look skeptically at life; he was later immortalized in Ruark's autobiographical novel, The Old Man and the Boy. Bobby had no siblings, but his parents later adopted a younger boy, David.

A bright youth, cocky and self-assured, Ruark was admitted to The University of North Carolina at age fifteen. There he drew cartoons for the Carolina Buccaneer and was graduated in June 1935 with an A.B. in journalism. Recommended by Professor Oscar J. Coffin, he was taken on as a cub reporter by the Hamlet News-Messenger. Ruark later commented, "I was the only guy that he considered mean enough and slap-happy enough to survive in that job." He found himself writing all the local news, selling subscriptions and advertising, helping make up the paper, and delivering it from door to door. In desperation he transferred to the Sanford Herald, but, not thriving there either, he came close to abandoning newspaper work forever. He took an accounting job with the Works Progress Administration in Washington, D.C., but soon enlisted as an ordinary seaman in the Merchant Marine. In 1936 he quit this too for a place as copy boy on the Washington Post. From there he quickly moved again, to the Star, and, finally, to the Washington Daily News, where he settled down happily.

In August 1938 Ruark married Virginia Webb, an interior decorator, of Washington, D.C. Having discovered the publicity value of stone throwing, he accused Detroit's pitcher, Bobo Newsom, of being a show-off and of fighting in the Shoreham Hotel. This led to a confrontation in the Tigers's locker room that started a free-for-all, got Ruark's name onto all the sports pages in the country, and gained him additional readers.

In World War II he joined the navy as a gunnery officer, with the rank of ensign, on munitions ships in the Atlantic and Arctic; later he was press censor under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz in the Pacific. In 1945 he returned to the Daily News, where he established himself as a Scripps-Howard syndicated columnist and by 1950 was earning $50,000 annually. Again employing his stonethrowing technique, he gained notoriety in August 1947 by "blowing a loud whistle" on Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee (Courthouse Lee) for Lee's misuse of government materials, maltreatment of subordinates, and other alleged abuses in Leghorn, Italy. The War Department officially cleared Lee, but Ruark claimed a technical victory in that Lee, who had sometime before requested retirement, soon received orders to return to the United States.

Ruark wrote lampoons on every conceivable topic from women's dress styles and southern cooking to Broadway columnists and psychiatrists. He did not, however, become embroiled in politics. "I'm a political eunuch," he said, "and I don't evaluate myself as a heavy thinker." But he was pleased when compared with Westbrook Pegler, "the best technical writer I ever read." He began to consider his writing seriously and turned out best-selling novels at the rate of one every year or two, although, as he pointed out, the research had often taken many years. In 1947 Grenadine Etching, a flip, brash take-off on the historical novel, a genre he claimed was traditionally of poor quality but needed only a bawdy heroine such as Grenadine to make it a success, sold over 40,000 copies. It was followed in 1952 by Grenadine's Spawn in the same vein. Meanwhile, there had appeared in 1948 I Didn't Know It Was Loaded, a collection of forty spicy essays gathered from his syndicated columns and, the next year, One for the Road, further satire on the contemporary scene. He was also publishing articles regularly in the Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, Pic, Esquire, and Field and Stream.

On the advice of his physician he took a year off and went with Virginia to hunt big game in Africa. Patterning his life on that of Ernest Hemingway, whom he admired extravagantly (Ruark even called his wife "Mama"), from 1950 onwards Ruark spent a good deal of time in Africa. In 1953 he published Horn of the Hunter, the story of an African safari, and in 1955, his first major success as a serious novelist, Something of Value, based on the racial strife that led to the Mau Mau uprisings. He made well over a million dollars from the royalties on the latter book and from the movie rights sold to Metro Goldwyn Mayer. He purchased a house, his "castle in Spain," at Palamos on the Costa Brava near Barcelona and also maintained a swank penthouse in London. In 1957 Ruark returned to visit in Southport, Wilmington, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill. At The University of North Carolina he discussed plans for a scholarship trust fund to be awarded on the basis of need alone. Having been "pinched for funds" as a student in the depression years, he said that he wanted his beneficiaries "to have a good time." The scholarships would be named for the four professors "I got the most from while I was at the University"—Oscar (Skipper) Coffin, Wallace Caldwell, Penrose Harland, and Phillips Russell. "They were the best," he said, "at preparing a person's mind to receive a little knowledge in subsequent years."

About 1963 he sold his grandfather's old house in Southport because, he said, "I do not think I could ever live with all the old ghosts." After that he did not go home again. Permanently settled in Spain, he wrote five more books: The Old Man and the Boy (1957), Poor No More (1959), The Old Man's Boy Grows Older (1961)—all autobiographical; Uhuru (1962)—another study of race relations in Africa; and The Honey Badger (1964)—his novel defining American womanhood. By the 1960s he and Virginia were divorced, and he became engaged to Marilyn Kaytor, food editor for Look magazine. In the last week of June 1965, however, Ruark suffered an attack at his home on the Costa Brava. Flown to London for medical treatment, he died there of internal bleeding. Accompanied by Miss Kaytor and Alan Ritchie, Ruark's longtime friend and secretary, his remains were returned to Spain and buried in the Colina LaFosca Cemetery near his home.

Ruark was an Episcopalian and a member of Phi Kappa Sigma. In his will, dated 6 May 1965, he left bequests totaling $125,000 to Alan Ritchie and others, with the bulk of his property divided equally between Virginia Webb Ruark and Marilyn Kaytor. His Rolls Royce and extensive library went to his literary agent, Harold Matson, and his private papers including letters, portraits, and other pictures to The University of North Carolina, where they now form a part of the university's manuscript collection.

References:

Beverly Lake Barge, "A Catalog of the Collected Papers and MSS of Robert C. Ruark" (M.A. thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1969).

Hardy Burt, "It's a Wonderful Life—for Ruark," Redbook (April 1948).

Dan Carlinsky, comp., A Century of College Humor (1971).

International Celebrity Register (1959).

William S. Powell, ed., North Carolina Lives (1962).

Robert C. Ruark Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

Who Was Who in America, vol. 4 (1968).

Additional Resources:

Flora, Joseph M., Amber Vogel, and Bryan Albin Giemza. Southern writers: a new biographical dictionary. Baton Rouge: Louisana State University Press. 2006. https://www.worldcat.org/title/southern-writers-a-new-biographical-dictionary/oclc/61309281 (accessed September 2, 2014).

Foster, Hugh W. Someone of vlaue: a biography of Robert Ruark. Agoura, Calif: Trophy Room Books. 1992. https://www.worldcat.org/title/someone-of-value-a-biography-of-robert-ruark/oclc/28945360 (accessed September 3, 2014).

Richard Gaither Walser Papers 1918-1988. The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/w/Walser,Richard_Gaither.html (accessed September 2, 2014).

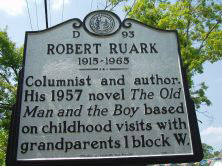

"Robert Ruark 1915-1965." N.C. Highway Historical Marker D-93, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=D-93 (accessed September 3, 2014).

Image Credits:

"Robert Ruark 1915-1965." N.C. Highway Historical Marker D-93, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=D-93 (accessed Mar. 6, 2024).

1 January 1994 | Glover, Erma Williams