North Carolina Academy of Science

See also: Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society.

The North Carolina Academy of Science is a significant part of the professional lives of the state's scientists. Organized in 1902, the academy sought to fill the need for collegiality among scientists who, as faculty members of underfunded colleges and universities, often could not attend national disciplinary meetings. State academies of science had proliferated in other regions of the country during the late nineteenth century, an outgrowth of the emerging spirit of professionalism among the nation's scientists. In addition to sponsoring annual meetings, these organizations endeavored to publish modest journals and to provide an avenue whereby scientists could offer their expertise for the public good.

The North Carolina Academy of Science is a significant part of the professional lives of the state's scientists. Organized in 1902, the academy sought to fill the need for collegiality among scientists who, as faculty members of underfunded colleges and universities, often could not attend national disciplinary meetings. State academies of science had proliferated in other regions of the country during the late nineteenth century, an outgrowth of the emerging spirit of professionalism among the nation's scientists. In addition to sponsoring annual meetings, these organizations endeavored to publish modest journals and to provide an avenue whereby scientists could offer their expertise for the public good.

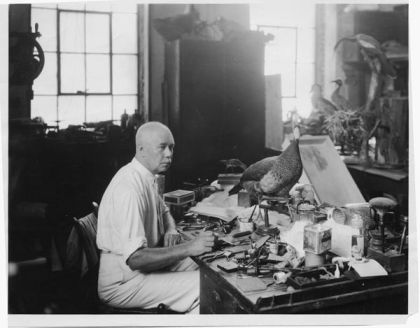

The idea for the North Carolina Academy of Science originated with William Willard Ashe, who, as forester for the North Carolina Geological Survey, did not benefit from even the limited professional contact within a university community. A group of Raleigh biologists, including Herbert Hutchinson Brimley, Franklin Sherman, and F. L. Stevens, quickly turned the idea into reality by soliciting support among their colleagues throughout the state and calling an organizational meeting in March 1902.

The academy limped along until 1909, when minor changes in membership requirements and the meeting format, as well as a membership drive, brought in 45 new associates. By 1920 membership totaled 112 persons; ten years later that figure had climbed to 305 persons. Membership declined a bit during the Great Depression, but following World War II it skyrocketed, reflecting primarily the expansion of institutions of higher education.

Although the North Carolina Academy of Science has always sought a broad membership, welcoming high school science teachers, industrial scientists, and state government employees, most members have come from colleges and universities. Consequently, the goals of the organization have reflected the professional needs of this group of scientists, including an opportunity to meet to discuss their research, a forum for the formal presentation of research results, and a publication outlet.

The academy achieved the first two of these goals; since 1909 annual meetings have attracted broad participation and offered wide-ranging programs. Prior to World War II, these meetings were often the only professional conventions that scientists attended. After the war, established scientists began to use the forum to announce research that they would flesh out in future publications, and young scholars, having  discovered the difficulty of accessing the programs of national meetings, were able to find a place on the agenda of the state academy and thus enter the professional world.

discovered the difficulty of accessing the programs of national meetings, were able to find a place on the agenda of the state academy and thus enter the professional world.

The academy was less successful in publishing a journal. In 1904 it teamed up with the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society to sponsor a joint publication and was able to produce a quarterly journal fairly regularly. The volumes, though, were often small and frequently appeared late. With minimum funding, editors who had academic responsibilities as well, and a membership that preferred to submit their most promising scholarship to a national journal first, the Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society was regarded as a secondary but nonetheless creditable professional publication.

Beginning in the 1920s, the North Carolina Academy of Science expressed concern over environmental issues and the quality of public education and made a number of efforts to influence legislation in these areas. These issues continued in the post-World War II era, culminating in such actions as the sponsorship of a Junior Academy of Science and high school science fairs (funded to a considerable extent by National Science Foundation grants). With the decline of federal funds in the early 1970s, the outreach programs contracted. In the early 2000s the academy continued to maintain both education and conservation committees that served a watchdog function, reacting when some aspect of their area of interest seemed threatened.

References:

Nancy Smith Midgette, "In Search of Professional Identity: Southern Scientists, 1883-1940," Journal of Southern History 54 (November 1988).

Midgette, To Foster the Spirit of Professionalism: Southern Scientists and State Academies of Science (1991).

Additional Resources:

The North Carolina Academy of Science: http://www.ncacadsci.org/

Image Credit:

William Willard Ashe created the idea for the Academy of Science. Image courtesy of UNC. Available from http://www.herbarium.unc.edu/Collectors/ashe.htm (accessed November 7, 2012).

Herbert Hutchinson Brimley, a founder of the Academy of Science, working in the Museum of Natural History, ca. 1937. Image courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

1 January 2006 | Midgette, Nancy Smith