Gold Mining in the Uwharries

"Mining for Mystery in the Uwharries"

by Kenneth W. Robinson

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

In the early decades of the 1800s, the southern Piedmont's gold mines attracted prospectors, investors, and miners. Tar Heel gold had first been found in 1799 on John Reed’s farm in Cabarrus County, several miles west of the Uwharrie Mountains. A lot of gold was recovered from the Reed Gold Mine, making Reed a wealthy man. Gold fever set in, as others tried to make their fortunes through mining. North Carolina experienced a gold rush in the 1820s and 1830s, becoming the nation’s largest producer of gold before the great California gold rush of 1849.

In the early decades of the 1800s, the southern Piedmont's gold mines attracted prospectors, investors, and miners. Tar Heel gold had first been found in 1799 on John Reed’s farm in Cabarrus County, several miles west of the Uwharrie Mountains. A lot of gold was recovered from the Reed Gold Mine, making Reed a wealthy man. Gold fever set in, as others tried to make their fortunes through mining. North Carolina experienced a gold rush in the 1820s and 1830s, becoming the nation’s largest producer of gold before the great California gold rush of 1849.

By the 1830s, gold prospectors and miners had moved into the Uwharrie Mountain region, searching the hills and panning the streams. Companies formed to finance mining operations. At least fifteen mines, including the Russell Mine, opened in the Uwharries before the Civil War. These included placer mines, where pressurized water was used to wash gold from hillsides; shaft mines dug into hillsides; and large, open pit mines. Later in the century, miners even used dredges (machines that remove earth) to search the sands of the Uwharrie River.

The Russell Mine was one of the largest gold mines in the Uwharries. Located in northern Montgomery County, it is near a crossroads aptly named El Dorado for the mythical city of gold that early Spanish explorers searched for. Archaeologists from Wake Forest University and the Uwharrie National Forest recently explored and began to document the historic mine site. One person involved with management of Russell Mine prior to the Civil War was Charles F. Fisher, a well-known industrialist and head of the North Carolina Railroad. After his death in the war, Fort Fisher on the coast of North Carolina was named for him.

Russell Mine was an open pit mine. The huge pit covers about an acre. Its walls reach much higher than some trees now growing in the bottom of the mine. Near the bottom of the pit, large tunnels extend sideways into the walls. A separate vertical shaft also was excavated near the open pit.

Workers dug quartz rock containing gold from the mine and carted it down the hill to a stamp mill next to a creek. There, crushers began the process of breaking the rock and getting gold from the ore. Steam engines powered the crushers and separators. The ruins of the brick stamp mill can still be seen today. Archaeological remains of homes, probably used by company supervisors, also have been found on nearby ridge tops. Only fireplaces remain visible above the ground.

Miners had to load rocks and ore into mining carts, operate hoists, keep steam engines stoked with wood, and—once gold was separated from rock—dispose of the rock (called spoil). They did much of the work by hand. For example, miners used sledgehammers to pound iron rods to bore small holes into the rock, which were then filled with dynamite used to blast rock loose.

Despite the hard work of many miners and the support of a well-financed mining company, the Russell Mine—like other mines in the Uwharrie Mountains—proved to be only somewhat successful. Though the mine operated off and on into the late 1800s, the gold-bearing rock strata eventually played out. The mine had to close. The amount of gold present in the hard rock was simply not enough to make mining profitable, long-term. Several other older gold mines in the Uwharries survived into the early 1900s, and newer mines opened in the area in the late 1800s and early 1900s. There even have been attempts to restart some mines within the last fifty years. However, few people have struck it rich mining gold in the Uwharries, and none of the mines operate today.

The clanging of ore crushers and mining tools no longer resounds through the forests of the Uwharries. But prospecting pits, open mines, and the ruins of mining operations can be found in many places. The Russell Mine is located on the present-day lands of the Uwharrie National Forest. The mine has been designated as a site with special historic significance, and the forest staff plans to document, preserve, and interpret it.

Kenneth W. Robinson, director of public archaeology at Wake Forest University, has thirty years of experience in North Carolina archaeology. He has excavated and studied many prehistoric- and historic-era sites but has a special interest in the archaeology of the 1700s and early 1800s, industrial archaeology, and prehistoric cultures of the Woodland period.

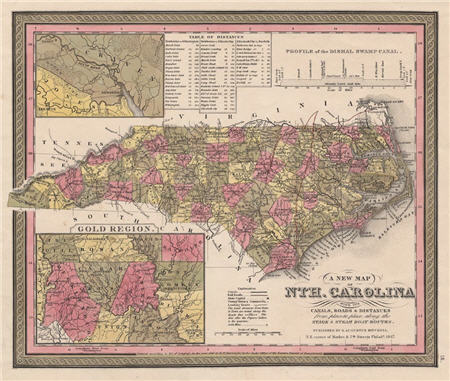

Image credit:

"Map of North Carolina showing gold regions." 1847. Online at Learn NC at http://www.learnnc.org/lp/multimedia/10025. Accessed 12/2010.

Additional resources:

Ballew, Sigrid and Jeff Reid. 2000. "Gold in North Carolina." North Carolina Geological Survey Web site. Online at http://www.geology.enr.state.nc.us/Gold%20brochure/Gold%20Brochure%2012222000.htm. Accessed 12/2010.

Learn NC resources about gold.

Resources on gold in North Carolina in libraries [via WorldCat].

1 January 2008 | Robinson, Kenneth W.