Frances "Frankie" Silver

by Maxine McCall

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Silver, Frankie, Murder Case

It was late December, and nineteen-year-old Charlie Silver had gone missing from his family’s small mountain cabin near the Toe River. “He lit out in the snow last night and never came home,” his young wife said.

When Charlie disappeared on December 22, 1831, heavy snow was falling. Did he slip through the ice on the frozen river? Was he wounded or killed by a bear or a mountain lion? Friends and neighbors searched the area for miles around.

After several days, a trapper named Jake Collis looked for clues to Charlie’s whereabouts at the Silver home. Collis dropped ashes from the fireplace into a bowl of water and found them “too greasy.” When he and other men tore up the floor in front of the hearth, they saw a blotch of blood “as big as a hog’s liver.” Outside, they found bits of bone and a heel iron from one of Charlie’s shoes buried in a hollow stump away from the house. Officials charged Charlie’s pretty wife, Frances “Frankie” Silver, with murder and carried her off to the Morganton jail.

Her trial in March of 1832 drew large crowds and stirred much talk. Streets became abuzz with courtroom tales of how petite Frankie (a teenage wife and mother) had killed her husband with an axe and then, to hide the crime, chopped up his body and burned the parts in the fireplace of their home in Mitchell County (Burke County, back then).

But just as chilling as the crime is the fact that Frankie Silver may have been wronged by the courts. The case brought against her seemed impossible to prove, there being little evidence (especially in the days before DNA testing or other modern methods) and no eyewitness to the crime except possibly the Silverses’ year-old daughter. Only Frankie could say what actually happened that night. But in 1832 (under a law unchanged until 1881), defendants did not testify in court. Frankie pled “not guilty,” and her lawyer did not press for a confession. “They won’t hang a woman,” he said.

After her trial and conviction, more than two hundred citizens begged two governors to pardon Frankie. Among them were the clerk of court, members of the jury that convicted her, and even her jailor. Some believed that Judge John R. Donnell should not have allowed jurors—who at first stood 9 to 3 in favor of acquittal—to reexamine witnesses who had discussed the case together after testifying. Some changed their testimonies, but the judge did not allow the lawyers to cross-examine them. Ruling on an appeal, the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the guilty verdict. And neither Governor Montfort Stokes nor his successor, Governor David Lowry Swain, granted Frankie Silver a pardon.

When the appeal failed, Frankie’s relatives made a desperate move to save her. In the dark of night, they helped her escape from jail disguised as a man. But after eight days, Frankie was caught and back behind bars, now chained to the floor. She lost all hope of saving her life.

Several weeks before her execution, Frankie made a full confession to her lawyer, Thomas Wilson. More than forty people read her testimony and signed petitions to Governor Swain saying that they believed she was telling the truth. According to them, Frankie killed Charlie in a “fracas” (a heated argument or fight). In the heat of the moment, Charlie had become so angry that he reached for his rifle. Frankie reacted by grabbing an axe to defend herself. She swung. And Charlie fell.

Frankie may not have been guilty of first-degree murder, but the jailbreak made her a convicted felon. Perhaps that is why the governors granted no pardon.

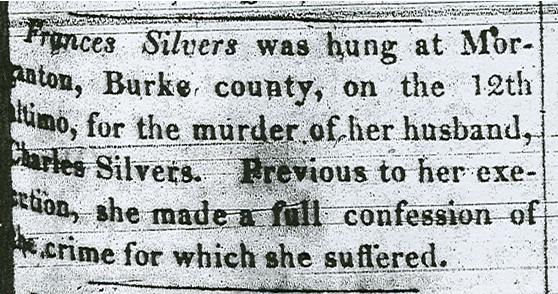

On July 12, 1833, many in the large crowd that witnessed her fate on the gallows believed Frankie to be the first woman hanged in North Carolina. Records show that she was not. But people still talk and write about her crime. The bloody violence of the tale repels, yet attracts, like a chilling ghost story told on a dark, windy night. And in the telling and retelling, Frankie Silver’s story has become a North Carolina legend.

Did Frankie Sing?

Many tales told through the years about Frankie are untrue. One is that she recited or sang a poetic confession from the gallows. Apparently, lyrics to a ballad about her were handed out at the hanging. The mournful song was widely sung in the mountains of North Carolina well into the 1930s. Frankie, however, did not write that song. It was written by a teacher named Thomas Scott, who changed the words of an old song, “Beacham’s Address,” to fit the story of Frankie’s crime. The song is not connected with the popular “Frankie and Johnny” ballad of later years, in which another Frankie “killed her man ’cause he done her wrong.” No evidence in documents relating to Frankie Silver’s trial suggests jealousy as a motive for Charlie’s death.

Maxine McCall—educator, conference speaker, and award-winning author—has done extensive research on the facts and folklore surrounding the case of Frankie Silver. Her resource book, They Won’t Hang a Woman (Heritage Edition), is used in the Burke County Public Schools. Dramatizations of her original story about Frankie Silver have aired on public television and the History Channel.

Resources:

North Carolina Digital Collections.

NCLive search on "Frankie Silver."

Price, Sharon (2003). "Frankie Silver: Tale of a murder and execution in myth, fact, and fiction," Special Collections Belk Library, Appalachian State University. http://collections.library.appstate.edu/research-aids/frankie-silver-tale-murder-and-execution-myth-fact-and-fiction

Tomberlin, Jason (2009)."July 1833 - Frankie Silver Hanged," This Month in North Carolina History, University Libraries, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill." http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/jul2004/index.html

WorldCat search on "Frankie Silver" (Searches numerous library catalogs).

Image Credits:

Star and North Carolina Gazette (Raleigh, N.C.), August 2, 1833. From Tomberlin, Jason (2009)."July 1833 - Frankie Silver Hanged," This Month in North Carolina History, University Libraries, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill."http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/jul2004/index.html

1 January 2008 | McCall, Maxine