Tobacco Barrels: Hogsheads

"Analyzing an Artifact: What in the World is a Hogshead?"

by Alison Holcomb

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2009.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Tobacco Barrels: Hogsheads; Tobacco; Tobacco Auctions; Inventions in the Tobacco Industry; Tobacco Belts; Hogshead

Just like letters, photographs, and birth records, artifacts such as the hogshead can serve as primary sources and provide firsthand evidence to historians. Even big tobacco barrels can tell stories that help people experience the past in a more authentic way. Analyzing the tobacco hogshead reveals the hard, heavy labor involved in tobacco’s sale and manufacture. Expanding that analysis to other primary and secondary sources about hogsheads helps us better understand tobacco’s importance.

Just like letters, photographs, and birth records, artifacts such as the hogshead can serve as primary sources and provide firsthand evidence to historians. Even big tobacco barrels can tell stories that help people experience the past in a more authentic way. Analyzing the tobacco hogshead reveals the hard, heavy labor involved in tobacco’s sale and manufacture. Expanding that analysis to other primary and secondary sources about hogsheads helps us better understand tobacco’s importance.

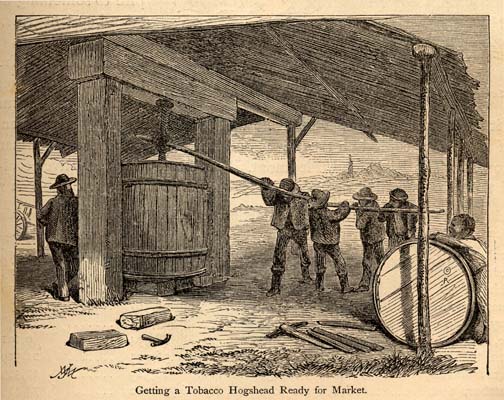

Secondary sources reveal that people used hogsheads to transport and store tobacco from the colonial period through the early 1900s. These barrels consisted of red or white oak staves (the long, vertical parts) and oak hoops, and they usually measured forty-eight inches in length and thirty inches in diameter at the head. After sale at a warehouse, leaf tobacco got pressed, or “prized,” into the hogshead. When full of leaf tobacco, hogsheads weighed about one thousand pounds each. Warehouse workers rolled them to buyers’ wagons or carts. At factories, workers then broke the hogsheads apart, emptied out the tobacco, and sold the barrel parts for scrap wood or firewood.

Just by examining the massive hogshead at Duke Homestead, staff learn something about tobacco warehouse and factory workers. The laborers assigned to roll such huge barrels around the warehouses, place them in carts and boats, and unload them at ports and factories must have been very strong. Moving these hogsheads was hard, hard work. The materials used, construction techniques, or markings on a hogshead might also give clues to where and when it was built. These details help track the movement of tobacco farming from community to community.

Taking the analysis further by consulting more sources reveals more details about the hogshead and tobacco history. Edmund Morgan’s book American Slavery, American Freedom explains that in colonial North America, tobacco held such importance that property was sometimes sold and taxes taken based on the hogshead of tobacco. Coopers who built hogsheads, therefore, had to follow strict instructions from colonial governments to avoid punishment for making hogsheads too big. The colony of Virginia’s 1752 Acts of Assembly state that “Coopers shall be placed under oath not to make tobacco hhds. larger than permitted by law, and to mark the true weight of every hhd. made, under penalty of 500 lbs. of tobacco for every infraction.” The fines assigned for hogshead infractions were half hogsheads of tobacco. Farmers who tried to cheat buyers by “exposing to sale or tendering tobacco... mixed with trash” faced penalties of a hogshead of tobacco. The crop was so important to colonial governments that it even became currency for fines for breaking laws.

We know a lot about the hogshead’s use and its significance, but that funny name has become one of the mysteries left to unravel. The hogshead was not employed only for tobacco; it traditionally is a measurement equal to 54 to 130 gallons and has been used to hold liquor, beer, flour, sugar, molasses, and other products. Most sources agree that the word hogshead dates to the Late Middle English period (1350–1469). Reasons behind the construction of the word remain less clear. One common theory focuses on the shape of the barrel, which resembles a hog’s snout. Another theory revolves around the word’s development and progression through different languages. Names for casks in several Teutonic, or Germanic, languages include oxhooft, oxehoved, and oxhufvod. It is, therefore, possible that the word originated as “oxhead.” The current word might have come from mispronunciations of the original. These early naming details show us that hogsheads fulfilled people’s storage and transportation needs for a long time.

At the time of this article’s publication, Alison Holcomb was working as the assistant site manager at the Duke Homestead State Historic Site in Durham.

Image credit:

King, Edward and James Wells Champney. 1875. "Getting a tobacco hogshead ready for market." The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. Online in UNC Libraries' Documenting the American South. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/king/ill407.html. Accessed 12/2010.

References and additional resources:

Duke Homestead Historic Site: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/duke/duke.htm. Accessed 12/2010.

Morgan, Edmund S. 1975. American slavery, American freedom: the ordeal of colonial Virginia. New York: Norton.

NC Digital Collections resources on tobacco in North Carolina (Government & Heritage Library and NC State Archives)

NC LIVE resources on tobacco and North Carolina

Resources in libraries about tobacco in North Carolina [via WorldCat]

Resources on tobacco on Learn NC.

1 January 2009 | Holcomb, Alison