COLONIAL PERIOD OVERVIEW

Excerpted from the North Carolina Manual, 2007-2008 edition.

See also: Colonial Agents; Colonial and State Records

Permanent Settlement

The first permanent English settlers in North Carolina emigrated from the tidewater area of southeastern Virginia. The first of these "overflow" settlers moved into the area of the Albemarle Sound in northeast North Carolina around 1650.

In 1663, Charles II granted a charter to eight English noblemen who had helped him regain the throne of England. The charter document contains the following description of the territory which the eight Lords Proprietor were granted title to:

In 1663, Charles II granted a charter to eight English noblemen who had helped him regain the throne of England. The charter document contains the following description of the territory which the eight Lords Proprietor were granted title to:

"All that Territory or tract of ground, situate, lying, and being within our Dominions in America, extending from the North end of the Island called Luck Island, which lies in the Southern Virginia Seas and within six and Thirty degrees of the Northern Latitude, and to the West as far as the South Seas; and so Southerly as far as the River Saint Mathias, which borders upon the Coast of Florida, and within one and Thirty degrees of Northern Latitude, and West in a direct Line as far as the South Seas aforesaid; Together with all and singular Ports, Harbours, Bays, Rivers, Isles, and Islets belonging unto the Country aforesaid; And also, all the Soil, Lands, Fields, Woods, Mountains, Farms, Lakes, Rivers, Bays, and Islets situate or being within the Bounds or Limits aforesaid; with the Fishing of all sorts of Fish, Whales, Sturgeons, and all other Royal Fishes in the Sea, Bays, Islets, and Rivers within the premises, and the Fish therein taken;

"And moreover, all Veins, Mines, and Quarries, as well discovered as not discovered, of Gold, Silver, Gems, and precious Stones, and all other, whatsoever be it, of Stones, Metals, or any other thing whatsoever found or to be found within the Country, Isles, and Limits ...."

The territory was to be called "Carolina" in honor of Charles I. In 1665, a second charter was granted to clarify territorial questions not answered in the first charter. This charter extended the boundary lines of Carolina to include:

"All that Province, Territory, or Tract of ground, situate, lying, and being within our Dominions of America aforesaid, extending North and Eastward as far as the North end of Carahtuke River or Gullet; upon a straight Westerly line to Wyonoake Creek, which lies within or about the degrees of thirty six and thirty Minutes, Northern latitude, and so West in a direct line as far as the South Seas; and South and Westward as far as the degrees of twenty nine, inclusive, northern latitude; and so West in a direct line as far as the South Seas."

Between 1663 and 1729, North Carolina was under the near-absolute control of the Lords Proprietor and their descendants. The small group commissioned colonial officials and authorized the governor and his council to grant lands in the name of the Lords Proprietor. In 1669, philospher John Locke wrote the Fundamental Constitutions as a model for the government of Carolina. Albemarle County was divided into local governmental units called precincts. Initially there were three precincts--Berkley, Carteret, and Shaftesbury--but as the colony expanded to the south and west, new precincts were created. By 1729, there were a total of eleven precincts--six in Albemarle County and five in Bath County, which had been created in 1696. Although the Albemarle Region was the first permanent settlement in the Carolina area, another populated region soon developed around present-day Charleston, South Carolina. Because of the natural harbor and easier access to trade with the West Indies, more attention was given to developing the Charleston area than her northern counterparts. For a twenty-year period, 1692-1712, the colonies of North and South Carolina existed as one unit of government. Although North Carolina still had her own assembly and council, the governor of Carolina resided in Charleston and a deputy governor appointed for North Carolina.

Royal Colony

In 1729, seven of the Lords Proprietor sold their interests in North Carolina to the Crown and North Carolina became a royal colony. The eighth proprietor, Lord Granville, retained economic interest and continued granting land in the northern half of North Carolina. The crown supervised all political and administrative functions in the colony until 1775.

Colonial government in North Carolina changed little between the proprietary and royal periods, the only major difference being who appointed colonial officials. There were two primary units of government--the governor and his council and a colonial assembly whose representatives were elected by the qualified voters of the county. Colonial courts, unlike today's courts, rarely involved themselves in formulating governmental policy. All colonial officials were appointed by either the Lords Proprietor prior to 1729 or by the crown afterwards. Members of the colonial assembly were elected from the various precincts (counties) and from certain towns which had been granted representation. The term "precinct" as a geographical unit ceased to exist after 1735. These areas became known as "counties" and about the same time "Albemarle County" and "Bath County" ceased to exist as governmental units.

The governor was an appointed official, as were the colonial secretary, attorney general, surveyor general and the receiver general. All officials served at the pleasure of the Lords Proprietor or the crown. The council served as an advisory group to the governor during the proprietary and royal periods, in addition to serving as the upper house of the legislature when the assembly was in session. When vacancies occurred in colonial offices or on the council, the governor was authorized to carry out all mandates of the proprietors and could make a temporary appointment until the vacancy was filled by proprietary or royal commission. One member of the council was chosen as president of the group and many council members were also colonial officials. If a governor or deputy governor was unable to carry on as chief executive because of illness, death, resignation or absence from the colony, the president of the council became the chief executive and exercised all powers of the governor until the governor returned or a new governor was commissioned.

The colonial assembly was made up of men elected from each precinct and town where representation had been granted. Not all counties were entitled to the same number of representatives. Many of the older counties had five representatives each, while those formed after 1696 were each allowed only two. Each town granted representation was allowed one representative. The presiding officer of the colonial assembly was called the speaker and was elected from the entire membership of the house. When a vacancy occurred, a new election was ordered by the speaker to fill it. On the final day of each session, bills passed by the legislature were signed by both the speaker and the president of the council.

The colonial assembly could not meet arbitrarily, but rather convened only when called into session by the governor. Since the assembly was the only body authorized to grant the governor his salary and spend tax monies raised in the colony, it met on a regular basis until just before the Revolutionary War. There was, however, a constant struggle for authority between the governor and his council on the one hand and the general assembly on the other. Two of the most explosive issues involved fiscal control of the colony's revenues and the election of treasurers. Both were privileges of the assembly. The question of who had the authority to create new counties also simmered throughout the colonial period. On more than one occasion, elected representatives from counties created by the governor and council without consulting the lower house were refused seats until the matter was resolved. These conflicts between the executive and legislative bodies were to have a profound effect on the organization of state government after independence.

References and additional resources:

Bassett, John Spencer. 1894. The Constitutional Beginnings of North Carolina (1663-1729). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bassettnc/menu.html.

North Carolina Digital Collections.

Internet Archive search on Colonial North Carolina (digitized texts)

North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. 2008. North Carolina's Beginnings. In North Carolina Manual, 70-73. Raleigh: NC Department of the Secretary of State.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2008. Colonial and state records of North Carolina. [Chapel Hill, N.C.]: University Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/.

Walbert, David. Governing the Piedmont. LEARN NC. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/governing-piedmont.

WorldCat subject searches (Searches numerous library catalogs):

Image credits:

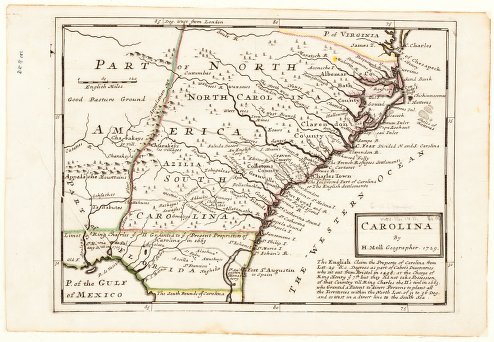

Carolina. 1729. From the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/355.

"King Charles II." From the North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA.

1 January 2007 | Anonymous