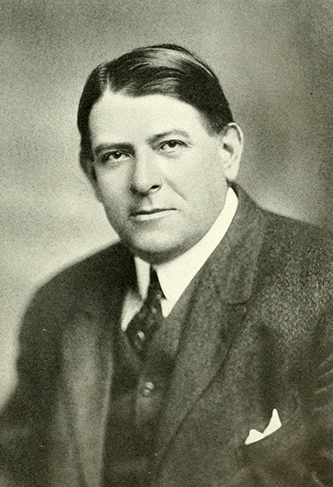

24 Oct. 1872–12 Jan. 1946

Walter (Pete) Murphy, lawyer and state legislator, was born in Salisbury, the son of Andrew, a local merchant, and Helen Long Murphy. He was the grandson of John Murphy, also a Salisbury merchant, and the great-grandson of James Murphy, a native of Glasgow, Scotland, who settled in Salisbury shortly before the American Revolution. On his maternal side, he was descended from local settlers of the 1750s and was a grandson of Dr. Alexander Long, Jr., a member of the class of 1813 at The University of North Carolina.

Murphy attended The University of North Carolina from 1888 to 1890, when he withdrew for two years. Returning in 1892, he enrolled in the law school. After receiving his law license in 1894, he established a practice in Salisbury. During the Spanish-American War, he served briefly in the navy.

Throughout his adult life, Murphy was an indefatigable campaigner for the Democratic party. Stumping tours carried him into all of the state's one hundred counties and, at the behest of the national committee, into other states as well. He was for several years a member of the executive committee of the state Democratic party, twice a delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1908 and 1932), and once (1908) an electorat-large. Murphy had two brief excursions into federal service. He served once as special assistant to the commissioner of internal revenue during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson, and he assisted in the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the Southeast under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In the General Assembly, Murphy represented Rowan County in the sessions of 1897, 1903–7, 1913, 1917, 1921–27, 1933, and 1937–39. He was speaker of the house during the extra session of 1913 and the regular session of 1917. In 1945 he was appointed liaison officer of the house and senate, a post especially created for him by the legislature in recognition of his long and outstanding service to the state. Although he never held a higher elective office, he became one of the best-known men in North Carolina, as well as one of the most influential. His gifts as a political orator and as an extemporaneous speaker of uncommon wit and his colorful personality combined to build him a far-reaching reputation while he was still in his twenties.

Murphy's celebrated memory for names, dates, faces, and facts served him well, both as a politician and as a student of history. While serving as reading clerk of the senate in 1899, he always called the roll from memory, sometimes in reverse alphabetical order. Because of his personality, he was often introduced as the "most popular man in the state." As a member of the General Assembly, Murphy backed increased state support for education, including the normal schools for Black children, for good roads, for those with physical and mental disabilities, and for assistance to war veterans, widows, and orphans. His attitude towards higher education was undoubtedly influenced by his lifelong ties with the university at Chapel Hill, where he served on the board of trustees and as a member of its executive committee for forty-four years, from 1901 until his death. When he was speaker in 1913, the university asked for its largest appropriation up to that time. After passage of the bill, Murphy returned to his home in Salisbury; in his absence, the bill was called back to the floor and was defeated.

The Raleigh Times in 1963 quoted a former house member, J. Wilbur Bunn of Wake County, on this incident: "Walter Murphy came back to Raleigh. I was sitting twenty feet from the man when he spoke and pleaded for the survival of the University of North Carolina. He had tears in his eyes and was mopping his face with his hand. When he finished his speech, at least ninety per cent of the representatives voted for the bill. It was the most thrilling experience I witnessed while here."

Securing every dollar possible for the state's institutions headed Murphy's legislative interests. At his death it was noted that many people had called "Walter Murphy, late of Rowan, 'the prince of parliamentarians' ever since he managed to get a $3,000,000 appropriations bill for state institutions through the house of 1917, without a dissenting vote."

In the 1920s Murphy took a vigorous stand against attempts to ban by law the teaching of the theory of evolution in the public schools and state-supported institutions of higher learning. In North Carolina, the acrimonious controversy on evolution reached a peak with the Poole Bill of 1925. Introduced in the General Assembly by David Scott Poole of Raeford and supported by powerful sectarian forces in the state, it would have prohibited teaching "as a fact Darwinism or any other evolutionary hypothesis." In the house debate, Murphy joined such able legislators as Henry Groves Connor, Jr., of Wilson, and Sam Ervin, Jr., of Morganton, in denouncing the antievolutionists. Murphy's eloquent address has been credited with having "clinched" the death of the antievolutionary movement in the legislature of 1925. The Poole Bill was rejected in the house by a vote of 67 to 46. Later that year The University of North Carolina awarded Murphy an LL.D. degree.

A steadfast Democrat, Murphy once ensured his own defeat by the voters of Rowan County rather than compromise his loyalty to the party. In 1928 he favored Senator James A. Reed of Missouri for the Democratic presidential nomination. But when the Democratic National Convention nominated Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York—whose candidacy was anathema to much of the South—Murphy campaigned on behalf of Smith and harshly denounced Senator Furnifold M. Simmons, the state's most influential Democrat, for refusing to do likewise. A candidate himself for the legislature that year, Murphy advised his constituents not to vote for him unless they could also vote for Smith. On election day, both he and Smith were repudiated at the polls. In 1930 Murphy supported Josiah W. Bailey in the heated Democratic senatorial primary in which Bailey defeated the once-powerful Senator Simmons.

For many years Murphy was interested in obtaining for the state a suitable memorial to be placed at the Gettysburg Battlefield in Pennsylvania in memory of North Carolina's Civil War dead. He was disappointed at what he regarded as the "pitiful pittance" allotted by the legislature for this purpose. After considerable effort by Murphy, the noted sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, was commissioned to construct a monument. Murphy made the dedicatory address at its unveiling on 3 July 1929. Public recognition for his work in behalf of Civil War veterans came in 1933, when he received the honorary appointment of inspector general of the North Carolina Division of United Confederate Veterans.

For thirty years Murphy was the state's foremost advocate of a "square deal" for Black citizens and fought for better educational opportunities for African Americans when Jim Crow was still firmly entrenched. Buildings were named for him at what is now North Carolina Central University, where he was a member of the board of trustees, and at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical University. He was the author of the "Murphy Law," which pushed North Carolina far ahead of other southern states in education for Black Americans.

Murphy never made the same speech twice. He appeared to absorb every fact that he encountered, cataloguing each in its allotted place in his memory, from which he could summon it at will. His library held more than three thousand books, and he was an authority on Napoleon. Many believed that Murphy knew more about the history of North Carolina than any of his contemporaries. The legislature of 1945 suggested that he write a history of the state, but approaching illness prevented him from such an undertaking. On the day of Murphy's death, the Salisbury Post observed: "It is commonly believed that a substantial total of the state's history vanished with Pete Murphy, and that a wealth of anecdote and reminiscences which only he could have committed to paper, go with him to the grave."

While a student in Chapel Hill, Murphy was cofounder of the Tar Heel and was its first business manager and second editor. He also founded the Psi chapter of Sigma Nu fraternity and became its first eminent commander. Moreover, he acted as personal secretary to university president, George T. Winston. For four years Murphy, who was six-feet-two and weighed two hundred pounds, played football at the university and was "centre rush" on its 1892 "all time wonder team." He once was said to have witnessed nearly seven hundred football games, most of them involving The University of North Carolina.

Murphy was cofounder of the Alumni Review in 1912 and served as president of the Alumni Association in 1922. He belonged to numerous civic and patriotic organizations, including the Masonic order, Elks, and Kiwanis. Murphy was a member of St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Salisbury. On 18 Mar. 1903 he married Maude H. Horney, a member of a Quaker family of Jamestown, N.C. She never participated in her husband's public life but was his constant inspiration and adviser at home. They were the parents of two children: Spencer, who became editor of the Salisbury Post, and Elisabeth, who married Peter Henderson. Following his death in Salisbury, Murphy was buried in City Memorial Park Cemetery.