See also: Poole Bills.

Conflicts involving the teaching of the theory of evolution in North Carolina schools came to the state in 1920 when T. T. Martin, a Mississippi native, criticized William Louis Poteat for teaching evolution in biology classes at Wake Forest College. Poteat, a biology professor and president of the college-as well as past president of both the North Carolina Academy of Science and the State Baptist Convention (SBC)-was placed in a difficult position. The SBC, which controlled Wake Forest College, was more theologically conservative than the college faculty, and the issue of teaching evolutionary theory was to be settled by a simple majority vote on a resolution at the SBC's annual meeting.

Martin and other antievolutionists accused Poteat of undermining biblical faith, thinking like a German militarist, and misappropriating school funds. They further held that the idea of evolution was responsible for virtually everything that was wrong with contemporary culture, from secularism, heresy, and sexual immorality to juvenile delinquency, atheism, and the "disintegration of the family." Poteat faced his detractors at the state convention in December 1922, when he argued for academic freedom in general instead of defending evolution specifically. The result was the passage of a resolution supporting Poteat and his values. Fundamentalist Baptists tried a second time in 1925 to have the state convention condemn the theory of evolution and Poteat, but they again failed.

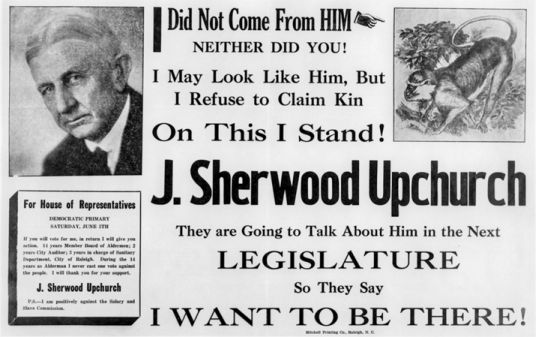

A second front for antievolutionary sentiment in the state arose in the General Assembly after David Scott Poole, running on a platform of opposition to Darwinism, was elected to the House of Representatives. His bill to prohibit the teaching of evolution in all tax-supported schools, including state universities, was passed by the Education Committee in January 1925. Sam J. Ervin Jr., then a first-year representative, later recalled the floor debate on the Poole Bill as the most interesting debate of his entire career. The Poole Bill failed, thanks to legislators who were alumni of the University of North Carolina or Wake Forest. A second Poole Bill also failed in 1927.

The curriculum guides for science education in North Carolina's public schools, revised occasionally by the Department of Public Instruction, have been consistently supportive of evolutionary principles. The guides of 1930 and 1935 endorsed the teaching of evolution and recommended certain facts to illustrate it. The 1941 guide was nothing less than an explicit, adamant, and detailed statement of evolutionary science. The 1953 and 1958 guides reaffirmed those policies.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some North Carolina schools suppressed the teaching of evolution, some presented it as scientific fact, and many found middle-of-the-road compromises, balancing explicit teaching of evolution with religious tolerance for those who could not accept its assumptions. In one notable incident in November 1971, the Gaston County Board of Education fired a substitute teacher for raising the topic of evolution and for offering incendiary opinions about the Bible in a junior high school history class. The teacher, George I. Moore III, sued in federal district court to regain his job, appealing to principles of academic freedom and the separation of church and state. The court ruled in Moore's favor.

While antievolutionary sentiment persisted across many decades, it lay dormant as a major public issue in North Carolina from 1927 until the early 1980s. Creationist successes in California, Arkansas, and Louisiana, and the rise of a powerful evangelical "Christian Right" in national politics, had again made the teaching of evolution a heated issue, and debate over the topic rekindled in the state. Jack Cavanagh, a first-year Republican senator from Forsyth County, introduced a bill in the General Assembly in 1981 to require that North Carolina's public schools teach evolution and creationism on equal terms in their science classes. The antievolution bills of the 1920s (including Tennessee's Butler Act and North Carolina's Poole Bills) had been intended to outlaw the teaching of evolution on the grounds that it contradicted the Bible. But those of the 1980s, including Cavanagh's, had a different goal; namely, inserting creationism into the public school science curriculum without trying to ban the teaching of evolution. Cavanagh's bill died in committee without attracting a single cosponsor, either Democrat or Republican.

Conservative Christians again tried to influence the status of evolution in the public school science curriculum in 1985, when they lobbied against the Standard Course of Study, a comprehensive curriculum for grades K-12 prepared by the Department of Public Instruction that emphasized critical reasoning. Ann Frazier, one of the Standard Course of Study's most vocal critics, accused it of being humanistic, anti-Christian, antifamily, and anti-God. (Actually, this document tiptoed around the creation-evolution controversy by never using the word "evolution" explicitly, although it certainly espoused evolutionary principles throughout its section on science.) The State Board of Education endorsed the Standard Course of Study in 1985. Also that year, the General Assembly approved a plan to finance it. Thus ended legislative efforts either to diminish evolution or to elevate creationism in the public school science curriculum.

However, creationist sentiment remained vibrant in many places throughout the state into the 2000s. North Carolina's creationists work through several local organizations, the most visible of which is perhaps the Triangle Association for Science of Creation. Creationist views are nurtured by a subculture of conservative Protestantism, and their principal source of inspiration, both spiritual and scientific, is the Institute for Creation Research in California. On the other side of the debate are groups such as the North Carolina Science Teachers Association, which defends evolution as unequivocal scientific fact and essential to a proper understanding of human life and civilization.