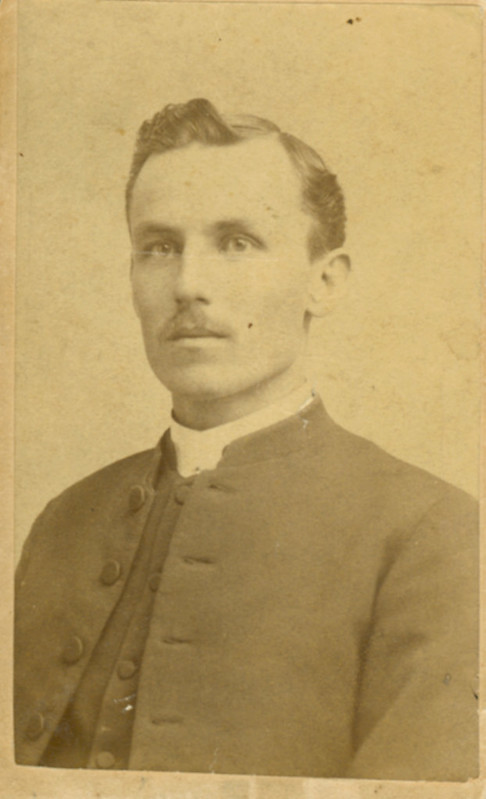

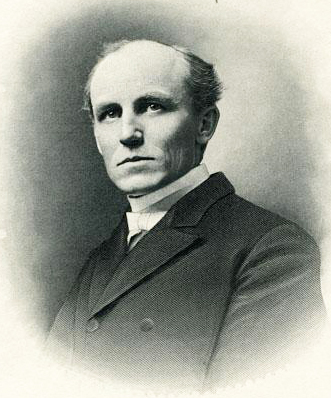

22 July 1861–11 Aug. 1922

See also: Bassett Affair

John Carlisle Kilgo, college president, Methodist bishop, and moral and religious leader, was born in a small brick parsonage in Laurens, S.C., the son of James Tillman and Catherine Mason Kilgo. His father, whose Scot-Irish ancestors were from Wake County, was a Methodist minister for thirty years; his mother was a native of Fairfield County, S.C.

Young Kilgo received his early education in the sections of South Carolina where his father preached. At McArthur Academy, which was organized along the lines of English schools with strict rules and discipline, he established his own lifelong code. Afterwards he attended Gaffney Seminary and in 1880 enrolled at Wofford College, which he was forced to leave at the end of his sophomore year because of poor eyesight. He then became a public schoolteacher for a year at Clio, S.C. In May 1882, he was licensed to preach and joined the South Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. His first charge was as a junior preacher on the Bennettsville Circuit. From 1882 to 1888 he served as a preacher in the South Carolina Conference. His appointments also included Timmonsville Circuit, Rock Hill Circuit, and Little Rock Circuit. He established a unique record as a public orator and became known as one of the outstanding preachers in the state.

In 1888 Kilgo was made financial agent of Wofford College, which was owned by the South Carolina Conference of the Methodist church. His duties were to increase the endowment of the college and to awaken greater interest in the school. In this capacity, he was able to continue his formal education, receiving the M.A. degree from Wofford in 1892. He was also appointed to the chair of philosophy and political economy. Later he received honorary degrees from Randolph-Macon and Wofford (doctor of divinity, 1895), Tulane University (doctor of laws, 1910), and Trinity College (doctor of laws, 1916).

His basic educational concept asserted that true higher education could be obtained only in institutions conducted under Christian auspices. Although an advocate of a strong public school system, he believed that higher education was the domain of private colleges rather than the state. Also at Wofford Kilgo developed his views regarding the education of women. In his opinion, women should receive the same educational opportunities as men; moreover, coeducation was the only answer because female colleges were inferior.

On 31 July 1894 Kilgo was nominated for president of Trinity College (now Duke University) and unanimously elected. He arrived in Durham and assumed the office on 16 August. On his first Sunday, he preached at both Methodist churches and captured the attention of the congregations. He immediately impressed the people of Durham with his ability as a preacher and an educational leader, demonstrating that he had a strong hold on Methodism in the state. There was a general rally behind him as he proceeded to rebuild the college.

Kilgo spent a large part of his first year at Trinity defending the cause of Christian education. In 1896, while still in his thirties, he joined Josiah W. Bailey, editor of the Biblical Recorder, in leading a statewide fight against taxes to support secular schools. To pursue his argument, he founded a monthly newspaper, the Christian Educator, which was published until 1898.

A personal and much publicized battle with one of his trustees began in June 1897 over a disagreement on faculty tenure. His opponent was Judge Walter Clark, a leading Methodist layman who, like Kilgo, was an able leader and a hard-hitting fighter. The two men exchanged a series of vituperative letters, which grew longer and more heated as time went on. In the dispute, the Trinity Board of Trustees supported Kilgo and asked Clark to resign. When the controversy was leaked to the press, Clark made further accusations and Kilgo called for an investigation to clear his name. Some of the statements made by the antagonists took them into the courts, and over the next several years there were three trials for slander and three appeals to the state Supreme Court. Finally, the case was dismissed and the dismissal upheld in November 1905. The Clark-Kilgo controversy was said to have mixed elements of "comic opera and war to the knife." The struggle was essentially a personal conflict between two strong-willed men who were accustomed to being "right."

Meanwhile, the resources of Trinity College grew in money, faculty, and equipment. In 1897 women began to arrive in modest numbers, and by the turn of the century the atmosphere of the college was attuned to the ambitions and attitudes of modern scholarship. In Kilgo, students and faculty had a champion who was increasingly disturbed about any restriction on their right to speak out. During his administration the college achieved a national reputation as a southern institution that permitted true academic freedom. This reputation was the result of his unshakeable convictions about, and constant fight for, the right of academic persons to enjoy free inquiry and free speech—rights that were widely denied and violated throughout the nation at the time.

The policy of academic freedom was tested in 1903 when Professor John Spencer Bassett published an article entitled "Stirring Up the Fires of Race Antipathy" in the South Atlantic Quarterly, a magazine he had launched. In his essay, Bassett suggested that politicians and political newspapers were exploiting the race issue for partisan ends. He predicted that blacks would win equality and called Booker T. Washington one of the greatest men born in the South, next to Robert E. Lee.

Led by Josephus Daniels, most of the Democratic press in North Carolina leveled a storm of abuse against Bassett and, in many cases, against Kilgo and the institution that harbored them. This occurred at a time when colleges had to worry about recruiting. In view of the uproar, Bassett offered to resign. The critical question became whether the trustees of Trinity, meeting in a special session on 1 Dec. 1903, would sacrifice the professor in order, presumably, to buy peace and public approval.

Though the students, faculty, and president of Trinity rallied wholeheartedly in defense of Bassett's right to free speech, the final power of decision lay with the trustees. After a long, dramatic meeting at which Kilgo made an impassioned plea for academic free speech, the trustees voted to refuse Bassett's resignation. In addition, they issued a ringing statement that has become one of the classic documents in the history of academic freedom in the United States.

By no means timid and indeed almost welcoming a fight, President Kilgo injected much of his own philosophy and personality into his statement of the spirit and purpose of the college. He made many contributions to the cause of higher education in the South, but his championship of academic freedom at Trinity has been considered by many as his most important educational work.

Kilgo is also credited for his part in stimulating the interest of the Duke family in the college—both through his close friendship with the family and by bringing outstanding teachers to the institution. It has been said that had it not been for Kilgo, there never would have been a Duke University.

During his sixteen-year tenure, Kilgo rebuilt Trinity from a small, poor college to one of the best known and most richly endowed institutions in the South while continuing the noble traditions already begun. In addition to raising scholastic standards, he remained true to his conviction that a school of higher education should make public opinion rather than be subservient to it. He maintained that Trinity should not avoid taking a stand on controversial issues for fear of adverse criticism. Under Kilgo's leadership, the search for truth became the primary concern of the school. Further, he upheld the religious and moral factors in higher education. He had a profound respect for the power of ideas, believing that "every thought left its mark somewhere." He never allowed the constituency of Trinity College or the citizens of North Carolina to forget that the forces or religion and education should unite in the common task of producing a nobler civilization.

Kilgo's moral and religious leadership extended beyond the campus. In constant demand as a preacher and lecturer, he was said to be the greatest preacher of his day in North Carolina. On many occasions Kilgo was asked to present the cause of Christian education in various sections of Southern Methodism. As a member of the General Conference from 1894 to 1910, he played an important role in the affairs of the denomination. In four consecutive General Conferences he was a member of the committee on episcopacy. In 1901 he was an official delegate from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, to the Ecumenical Methodist Conference in London.

His educational and religious leadership led to Kilgo's election as bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South—on the first ballot—at the General Conference in 1910. He was consecrated on 19 May. Because his episcopal duties made it impossible for him to continue as president of Trinity College, he tendered his resignation to the board of trustees on 3 June 1910 and retired from the post on 1 July.

In view of his many years of service to the college, and the value that might come from his continued presence, a home was erected for him at the northeastern corner of the campus. In 1912 the first number of the college annual was dedicated to Bishop Kilgo. He served on the board of trustees from 1910 to 1917 and in the latter year as chairman. In June 1915 the board elected him president emeritus, a salaried position with the duties of advising and assisting the executive committee and his successor, President William P. Few. During this time his ties with the Duke family and the Methodist church also continued to benefit the college.

By 1914 Kilgo's residence in Durham was proving too taxing. Because his episcopal duties required constant travel, mostly to the west, he decided to move to Charlotte. Shortly before his departure, he became involved in one more controversy which led to a sad break with the college. On Thanksgiving two students hoisted a sophomore class pennant, bearing the numerals "17," to the top of the campus flagpole. Kilgo, who had made much of the flagpole, considered the "treasonable" act to be a desecration of Old Glory. Becoming angry, he inquired whether the guilty parties were "sons of buffaloes," denounced them publicly, and demanded that they be found. The incident was blown out of proportion and Kilgo left, disappointed that the board took no action.

More than that, he was unwilling to forgive and forget. He believed the offending students should not receive their degrees. At the board meeting in June 1917, Kilgo was elected chairman to replace the former chairman, who had just died. When the names of the graduates were presented for approval, he refused to vote for them and sign their diplomas. The board overruled him and the diplomas were signed by the vice-chairman. On 21 November, the board accepted his resignation as trustee and president emeritus. At the time he was described as "the real builder of the new Trinity," and his moral leadership was singled out as his most significant contribution.

As bishop, Kilgo impressed those who heard him with his deep spirituality and evangelistic consecration. He electrified audiences throughout the state and the South. "With an eye that shone like an eagle, a high forehead, projecting chin and stentorian voice, he could thrill multitudes as few men ever could." Soon after taking office, the bishop was involved in the church battle on unification, which he strongly opposed.

Kilgo was a member of the Education Commission of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, which founded and incorporated Emory University. He was a trustee from 1915 and vice-president of the board from 1917 until his death. In 1916 and 1917 he was a special lecturer on homiletics at Emory. After 1918 his health gradually failed, and by 1920 he was relieved of his episcopal duties. In 1922, while returning from the General Conference at Hot Springs, Ark., Kilgo became seriously ill. He died of a bone malignancy in Charlotte, where he was buried.

On 20 Dec. 1882, Kilgo married Fannie Nott Turner of Gaffney, S.C. They had five children: Edna Clyde, James Luther, Walter Bissell (who died at age six), Fannie, and John Carlisle, Jr.

Many of Kilgo's sermons were published. His writings, articles, and personal papers are in the Manuscript Department of the Perkins Library of Duke University, which also maintains several portraits.