Southern Flying Squirrel

Glaucomys volans

by Lawrence S. Earley

by Lawrence S. Earley

Updated by Christine Kelly

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Classification

Class: Mammalia

Order: Rodentia

Family: Sciurdae

Size

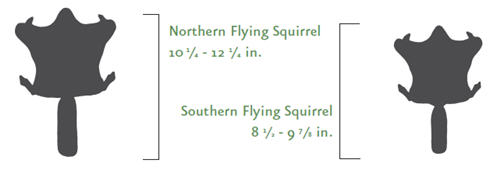

Length: From 8 1/2 to 9 7/8 in., including a 3- to 4-in. tail.

Weight: Adults weigh no more than 2 or 3 oz.

Food

Food

Omnivorous. Acorns and nuts carry them through the winter. Fruit, berries, flower blossoms and buds in season. Bird nestlings and eggs, animal carcasses.

Breeding

Twice a year, in January and February and again in June and July. Not all females breed twice.

Young

Produce 1 to 6 young although the average litter contains two to three young. Gestation is 40 days. They weigh less than a quarter of an ounce at birth. Young can glide in 8 weeks. Squirrels stay with their mother until the next litter is born. Young mature in one year.

Life Expectancy

Up to 13 years in captivity, but rarely more than five years in the wild. Predators include owls, hawks, snakes, bobcats, raccoons, weasels and foxes.

Range and Distribution

Range and Distribution

The southern flying squirrel is found throughout North Carolina, in urban areas as well as in forests, in the lowlands of the Coastal Plain and at elevations up to 4,500-5,000 feet. It ranges along the East Coast, north into southwestern Ontario and south into Mexico. Its close kin, the northern flying squirrel, roams throughout Canada, down into some of our northern states and along the Appalachian spine.

General Information

This diminutive rodent with the big saucerlike eyes is probably the most common mammal never seen by humans in North Carolina. It occupies habitat similar to that of the gray squirrel and, to a lesser extent, the fox squirrel, yet because it is a nocturnal species, it is not seen as often as the other two. It is truly arboreal, gliding from tree to tree on folds of outstretched skin.

Description

Description

The southern flying squirrel is smaller than its northern cousin and ranks as the smallest of the state’s 5 tree squirrel species, which include the red squirrel, fox squirrel and gray squirrel. It weighs no more than 2 or 3 oz. and measures from 8 1/2 in. to 9 7/8 in., including a 3- to 4-inch-long tail. Its fur is a lustrous reddish brown or gray, although its belly is counter-colored a creamy white.

This squirrel’s most distinctive feature is the cape of loose skin that stretches from its wrists to its ankles and forms the membrane on which it glides. The membrane is bordered in black. When the squirrel stretches its legs to their fullest extent, the membrane opens and supports the animal on glides of considerable distance.

Flying squirrels produce a birdlike chirping sound. Some of their vocalizations are not audible to the human ear.

History and Status

The southern flying squirrel is 1 of 2 flying squirrels found in North America — the other one is the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus). A total of 35 species of flying squirrels in the family Sciuridae exists worldwide, most of them in Asian countries. Both southern and northern flying squirrels are found in North Carolina, although the northern flying squirrel is rare, occurring at higher elevations on only 5 or 6 mountain ridges in the western part of the state.

Flying squirrels are a nongame species, but only the Carolina northern flying squirrel is listed as an endangered species by the federal government.

the federal government.

Habitat and Habits

Southern flying squirrels live in hardwood and mixed pine-hardwood forests. They require older trees with cavities for roosting and nesting, and in winter readily roost together in surprisingly large numbers. Tree cavities have been found with as many as 50 roosting squirrels. Because of their need for tree cavities for habitat, they are a natural competitor for woodpecker’s homes. Flying squirrels prefer cavities with entrances from 11/2 to 2 in. in diameter but will also customize holes to fit. In Sandhills longleaf pine forests, where suppression of natural periodic fires has allowed scrub oaks to grow in dense thickets, southern flying squirrels have been known to occupy the pine cavities of the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

The most distinctive trait o f the squirrel is the way it glides from tree to tree. It does not “fly” so much as it parachutes. When it desires to travel about its home range, it climbs to the top of a tree and jumps. The gliding membrane billows up, and by varying the tension on its membrane and using its tail as a rudder, the squirrel can direct its “flight” around branches and other obstacles with remarkable agility. It can turn suddenly at a 90-degree angle to the direction of its glide. The longest flight at one time has been measured at around 200 ft., although typically the distance is much shorter. The flying squirrel lands hind feet first, head up, and scampers to the other side of the tree to avoid detection. It glides downward at about a 30-degree angle. Thus on a long journey, flying squirrels repeatedly climb and glide until they reach their destination. In this way, a flying squirrel is able to cover large distances, exploiting patchily distributed resources. Like other squirrels, the southern flying squirrel can hop from branch to branch and spends considerable time foraging on the ground.

f the squirrel is the way it glides from tree to tree. It does not “fly” so much as it parachutes. When it desires to travel about its home range, it climbs to the top of a tree and jumps. The gliding membrane billows up, and by varying the tension on its membrane and using its tail as a rudder, the squirrel can direct its “flight” around branches and other obstacles with remarkable agility. It can turn suddenly at a 90-degree angle to the direction of its glide. The longest flight at one time has been measured at around 200 ft., although typically the distance is much shorter. The flying squirrel lands hind feet first, head up, and scampers to the other side of the tree to avoid detection. It glides downward at about a 30-degree angle. Thus on a long journey, flying squirrels repeatedly climb and glide until they reach their destination. In this way, a flying squirrel is able to cover large distances, exploiting patchily distributed resources. Like other squirrels, the southern flying squirrel can hop from branch to branch and spends considerable time foraging on the ground.

Mothers will move their young if their nest is disturbed. If a nest tree falls, for example, the mother grasps one of her babies by the slack skin of its belly, climbs a tree holding it in her mouth and glides to the new nest location. Returning by the same route, she repeats these steps until all of her young are moved. Males do not assist with the rearing of the young squirrels.

Southern flying squirrels seek nests in hardwood trees that provide cavities, and seeds and nuts. A typical nest will be lined with finely chewed bark, especially cedar bark in the east, and grasses. Lichen, moss and even feathers provide a soft bed. The squirrels are omnivorous. They store hard mast — nuts and acorns — in nests, in tree crevices and on the ground. They also eat fungi, berries, fruits and seeds, flower blossoms and buds in season, and even animal carcasses, bird eggs and nestlings.

People Interactions

Though the nocturnal activities of southern flying squirrels make them hard to detect, they will take up residence in just about any kind of nest box in a suburban setting as long as deciduous trees are nearby. Bluebird boxes attract flying squirrels.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can Help

Southern flying squirrels are periodically encountered by NCWRC biologists during surveys for red-cockaded woodpeckers in the Sandhills. They are occasionally captured incidentally in squirrel boxes or traps during surveys for the rarer Carolina northern flying squirrel, particularly in the mountains where their ranges overlap. This species does quite well in a variety of habitats and, in general, populations seem to be stable and/or expanding in some areas. In fact, where the two species overlap, southern flying squirrels may actually out-compete northern flying squirrels for available resources. NCWRC biologists are considering management strategies that favor northern flying squirrels and discourage southern flying squirrel encroach ment in appropriate habitat at elevations above 4500 ft.

Southern flying squirrels are also known to take up residence in attics of suburban and rural residences. Although they can make quite a racket, they don’t generally pose any significant problems for the homes they occupy. However, there are many nonlethal and humane exclusion techniques that can be used to evict the squirrels. Contact your local Wildlife Damage Control Agent for suggestions.

References:

Boynton, Allen. “Northern Flying Squirrel,” Wildlife Profiles, Set 5 (N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, 1994).

Earley, Lawrence S. “Tree-top Rivals,” Wildlife in North Carolina, February 1984, pp. 23-27.

Scheibe, JS, KE Paskins, S Ferdous, and D Birdsill. 2007. Kinematics and functional morphology of leaping, landing, and branch use in Glaucomys sabrinus. J. Mammal. 88(4):850-861.

Webster, David, James F. Parnell and Walter C. Biggs Jr. Mammals of the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland (University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

Credits:

Photos by Dave Maslowski and North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Produced by the Division of Conservation Education, Cay Cross–Editor, Carla Osborne–Designer.

17 June 2010 | Earley, Lawrence S. ; Kelly, Christine