WWI: Last days of the War

Peace without victory

On the cold night of November 10, 1918, Sergeant Noah Whicker, 321st Infantry Regiment, 81st Division, could not sleep. He stayed awake in the trenches and “walked all night to keep from freezing.” The Forsyth County native had a lot on his mind. He had heard rumors that the war might end soon. The next morning he was to lead his platoon over the top to attack the Germans.

On the cold night of November 10, 1918, Sergeant Noah Whicker, 321st Infantry Regiment, 81st Division, could not sleep. He stayed awake in the trenches and “walked all night to keep from freezing.” The Forsyth County native had a lot on his mind. He had heard rumors that the war might end soon. The next morning he was to lead his platoon over the top to attack the Germans.

That same night Private First Class (PFC) William Morris, 365th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division—an all-black division—and his friends sat up talking about the possible end of the war. That afternoon the African-Americans had taken several German prisoners. The Stokes County native recalled, “One of them [the Germans] said, ‘Tomorrow at 11:00 Deutschmann free.’ He knew more about it than I did.”

German military and civilian leaders had known as early as August that the war was lost. The United States was sending thousands of troops to fight on the western front each month. That spring and summer, General Erich von Ludendorff’s German armies had failed to break through British and French lines in five major offensives, largely because of American reinforcements. From June through October, the Allies drove the Germans back in battle after battle.

On September 26, General John J. Pershing’s American army began the Meuse-Argonne offensive to smash through enemy lines and end the war. As the battle raged on into October, the German lines slowly crumbled away. Germany’s generals knew the Americans would soon break through and cut the important railroad supply line in Sedan, France.

On October 6, the Germans sent a message to United States President Woodrow Wilson asking for peace. In January, Wilson had outlined “Fourteen Points” he thought Germany should have to agree to before the war could end. Through the entire month of October the two governments sent messages back and forth, trying to reach an understanding.

General Ludendorff was forced to resign on October 27. General Pershing renewed American attacks on the Meuse-Argonne front on November 1. By November 7, the Sedan railroad was cut. The German armies were divided, and some were cut off from all supplies and reinforcements. Back in Germany, the political and economic systems were falling apart. Riots broke out in the streets of several cities. Soldiers refused to go to the front to fight. Then, on November 9, Kaiser Wilhelm, supreme ruler of Germany, abdicated and fled to Holland.

American soldiers fighting in the trenches did not know what was happening in Germany. They did not know that the German government had asked for terms to end the war. Every day the Americans attacked again, trying to break through enemy lines. The Germans defended their positions with terrible machine gun and artillery fire. In every attack thousands of American soldiers were wounded or killed. But they kept attacking because they believed the Germans were near defeat.

General Pershing was not happy when he found out that the Germans wanted an armistice to end the war. It would allow the German armies to return home undefeated, and he feared that would encourage them to fight again in the future. Before the war stopped, Pershing strongly believed that the German armies ought to be forced to surrender and the German government ought to admit defeat. Otherwise, the country should be invaded. President Wilson and the Allied leaders overruled Pershing and agreed instead to sign an armistice.

On November 7, German and Allied delegates met to discuss terms of the armistice. The papers were signed at 5:00 a.m. on November 11. However, the cease-fire would not go into effect until eleven o'clock the same morning. After that, the German armies would return home to wait for a final peace treaty to be signed. General Pershing was told of the armistice at 6:00 A.M. His soldiers would not be told.

PFC Felix Brockman of Greensboro was trying to sleep in a bombproof dugout the night of November 10. He was lying off to the side in the dark when some officers came in for a meeting. Like Brockman, they were all members of the 321st Ambulance Company, 81st Division. Brockman recalled, “[Captain W. E.] Brackett said, "Tomorrow at 11:00 A.M. there could be an armistice,’” and he said to tell no one his news. Then the captain told his men to prepare for casualties to come in from the front, because the infantry would attack the next morning.

Just before dawn, Whicker prepared himself and the infantry of Company D to go over the top. Knowing nothing about the armistice, they climbed out of the trenches and attacked the Germans at 6:00 A.M. The advance had scarcely begun when the Americans were met with heavy machine gun and artillery fire.

“We were lucky that morning. . . . ” Whicker recalled. “They would have killed us all if it had not been foggy.” Under intense fire, he attempted to run forward a few times. But every time he started, the Germans “cut weeds down around me” with machine gun fire.

A few hundred yards away from Whicker, Corporal John Adams and the men of Company C were having an equally difficult time. Adams recalled, “We were taking machine gun fire and we were crawling on the ground. The shells were bursting overhead and the machine gun bullets were hitting all around.” The corporal from Rockingham County was caught in open ground with his men by the deadly enemy fire.

Like Americans all along the battle lines that morning, soldiers of the 81st Division endured five long hours of combat. Then, all at once, everything stopped. It was exactly 11:00 A.M. Corporal Adams did not know what to do. He remained on the ground until he saw a lieutenant walk out in front of his men. “The lieutenant hollered, ‘It’s all over, the war is over, it’s all over and you can go home now!’ We started getting up pretty fast after it got quiet, and some of the boys were hugging each other.”

Back in the field hospital behind the lines, Brockman was busy with the wounded who were being brought in from the front. The war was over, but hundreds of wounded men filled the triage area where Brockman was working. His job was to remove their equipment and bloodstained clothing so the doctors could operate.

Brockman never forgot one injured soldier. He had a bad shrapnel wound in his right shoulder. When they took his blanket off, his arm dropped down, over the side of the stretcher, hanging by just a little muscle. And he said, “Oh God, why did they send us over the top when they knew it was going to end?”

At the time of this article’s publication, R. Jackson Marshall III served as chief curator of the North Carolina Museum of History. Marshall, author of Memories of World War I: North Carolina Doughboys on the Western Front (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, 1998), became keenly interested in World War I while talking to his grandfather, who fought in and was wounded during the war.

Additional resources:

Brockmann, Felix. "Here, There, and Back." Record Source: Box 5, Folder Brake-Bryan within Personal Records, Compiled Individual Service Records. State Archives of North Carolina. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/twc/twc.aspx?appId=1001&file=data/records.xml&style=styles/recordDetail.xsl&styleParams=recordId=128

Johnson, Clarence Walton. 1919. History of the 321st infantry with a brief historical sketch of the 81st division, being a vivid and authentic account of the life and experiences of American soldiers in France, while they trained, worked, and fought to help win the world war ; "Wildcats". NC Digital Collections. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/history-of-the-321st-infantry-with-a-brief-historical-sketch-of-the-81st-division-being-a-vivid-and-authentic-account-of-the-life-and-experiences-of-american-soldiers-in-france-while-they-trained-worked-and-fought-to-help-win-the-world-war-wildcats/1939616

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/world-war-i

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

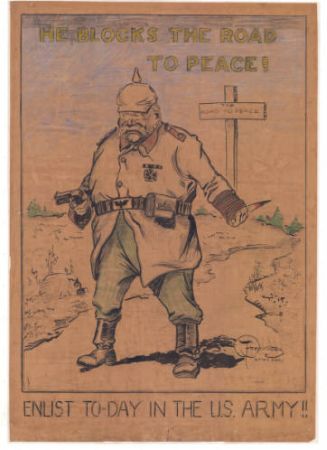

Image credit:

Owen, Fred V. 1918. "He blocks the road to peace!" State Archives of North Carolina. Call no. MilColl.WWI.Posters.1.10. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/he-blocks-the-road-to-peace/553407

1 May 1993 | Marshall, R. Jackson, III