Bennett College

Bennett College is a historically black, private, liberal arts university for women located in Greensboro. It is one of only two women’s HBCUs in the United States and has connection to the United Methodist Church.

The college’s origins can be traced to the basement of Warnersville Methodist Episcopal Church (now St. Matthew’s United Methodist Church) beginning in 1873. The coeducational institution was founded by newly emancipated enslaved people with the intentions of educating recently freed enslaved people and training teachers. The curriculum at the time was that of a normal school, a vocational school for teachers. Funding for the early days of Bennett came from the Freedman’s Aid and Southern Education Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. As the college grew, it attracted the attention of a wealthy white benefactor, Lyman Bennett of Troy, N.Y. His donation of $10,000 (equivalent to $243,580 in 2022) was used to purchase the ground upon which the college’s first building was erected. While in the process of fundraising for Bennett’s iconic bell, Lyman Bennett died of pneumonia. The first building, Bennett Hall, and the school were named in his honor.

The college’s origins can be traced to the basement of Warnersville Methodist Episcopal Church (now St. Matthew’s United Methodist Church) beginning in 1873. The coeducational institution was founded by newly emancipated enslaved people with the intentions of educating recently freed enslaved people and training teachers. The curriculum at the time was that of a normal school, a vocational school for teachers. Funding for the early days of Bennett came from the Freedman’s Aid and Southern Education Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. As the college grew, it attracted the attention of a wealthy white benefactor, Lyman Bennett of Troy, N.Y. His donation of $10,000 (equivalent to $243,580 in 2022) was used to purchase the ground upon which the college’s first building was erected. While in the process of fundraising for Bennett’s iconic bell, Lyman Bennett died of pneumonia. The first building, Bennett Hall, and the school were named in his honor.

Bennett’s enrollment, programs, and campus grew. In 1879, the school had just under 250 students enrolled. There were three levels of study: English (elementary level), Normal (vocational teacher’s school), and Theological studies.

The year 1889 was a year of much positive change for the school. It was in this year that the school was officially charted as a college by the state. On March 11, 1889, the institution became officially known as Bennett College. This year was also the first under the leadership of Bennett’s first black president, Dr. Charles N. Grandison. Dr. Grandison was the first black president of any Freedmen’s Aid and Southern Education Society school. It was also during this time that the college introduced an athletic program.

Under the leadership of college presidents Dr. Jordan Chavis and Rev. Silas A. Peeler, Bennett became one of the first institutions to offer coursework in African American History.

In 1926, the college saw major reorganization. A study by the Board of Education and the Women's Home Missionary Society (WHMS) and a survey done by the Phelps-Stokes Foundation recommended Bennett College be transitioned from a coeducational institution into a college for women. The WHMS had previously voiced that an institution of higher education was needed for black women. After naming a board of trustees and surveying the campus, the next step was naming a new president.

In May of 1927, Dr. David Dallas Jones was inaugurated as Bennett College’s president. At the beginning of his presidency, the course schedule included four years of high school and only two years of college work. As demands and preparation of the students increased, two years of the college level courses were added, making Bennett College both a four-year high school and a four-year college.

In May of 1927, Dr. David Dallas Jones was inaugurated as Bennett College’s president. At the beginning of his presidency, the course schedule included four years of high school and only two years of college work. As demands and preparation of the students increased, two years of the college level courses were added, making Bennett College both a four-year high school and a four-year college.

Dr. Jones’ presidency saw the establishment of many new traditions, including the Campus Illumination Ceremony, White Breakfast, and the Home Making Institute. The Home Making Institute invited prominent guests such as Eleanor Roosevelt to visit campus and speak. Other traditions established at this time were those specific to dress code. The students were limited to wearing pants and shorts during recreational activities, work, and breakfast. To go downtown, the students were required to wear dresses with hats and gloves. This remained the expectation until the 1960s when the students sought to change this dress code through a series of protests.

Unlike other university and college leaders during the time, Dr. Jones always sought to stay in touch with his students and was known for openly supporting activism while speaking out against white supremacy and segregation. It was common to see him sitting on the steps of the chapel speaking informally with students and he went on air on the local airwaves. Dr. Jones led the college until 1955 and his supportive and close-knit style of presidency would be maintained by subsequent Presidents of Bennett College, including Dr. Willa B. Player.

Dr. Willa B. Player was inducted as Bennett’s first female President in 1955 and was the first black female president of any private 4-year college. Under Dr. Player’s leadership came another new era for Bennett. Highlights of her time include establishing academic committees to improve the academic program, gaining full membership in the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, and her invitation to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.. Dr. King answered this invitation and spoke on campus in 1956; this was the sole speech of Dr. King’s in Greensboro. It was also during her presidency that the students of Bennett were active in protests of the Civil Rights era.

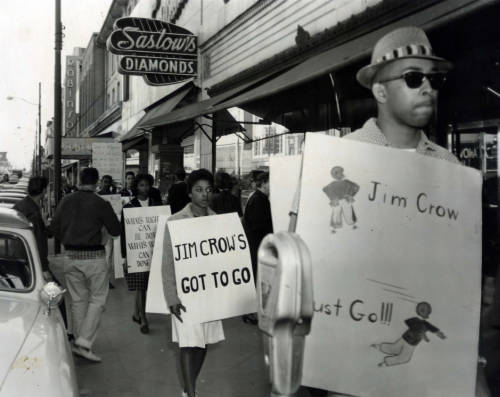

Joining with the students at A&T University, students known as Bennett Belles were heavily involved in the Woolworth sit-ins in the 1960s, going so far as to plan and organize the sit-ins alongside the A&T four, also known as the Greensboro four. In addition to the sit-ins, the Belles also protested against local stores with discriminatory employment practices. The 1960s also saw the creation of “Operation Doorknock,” which was organized by the students during the 34th annual Home Making Institute. Operation Doorknock was an effort of the Bennett Belles to increase voter turnout; the students went door-to-door in the surrounding black communities and encouraged them to vote.

Joining with the students at A&T University, students known as Bennett Belles were heavily involved in the Woolworth sit-ins in the 1960s, going so far as to plan and organize the sit-ins alongside the A&T four, also known as the Greensboro four. In addition to the sit-ins, the Belles also protested against local stores with discriminatory employment practices. The 1960s also saw the creation of “Operation Doorknock,” which was organized by the students during the 34th annual Home Making Institute. Operation Doorknock was an effort of the Bennett Belles to increase voter turnout; the students went door-to-door in the surrounding black communities and encouraged them to vote.

In 1966, Dr. Issac H. Miller, Jr. succeeded Dr. Player as College President. His presidency came at a particularly turbulent time and protests frequently occurred inside and outside of the campus. Inside of the campus, students were protesting strict curfew times and dress codes, while outside, the events of the Civil Rights era, particularly the assassination of Dr. King Jr., caused waves of unrest. Much like his predecessors, Dr. Miller prioritized understanding and listening to his students in times of trouble and disagreement.

Dr. Miller was extremely active in fundraising for Bennett College, with many personal visits to foundations alongside his active involvement with the Second Century Campaign Fund and the United Negro College Fund Campaign. It was also during his presidency that the first sorority on campus was established in 1969, Alpha Kappa Mu. Dr. Miller served as College President until 1987 at which time Dr. Gloria Randle Scott was selected as his predecessor. Fostering community and building relationships with their students has remained a focus of each of Bennett’s College Presidents. They have invited guests including Maya Angelou, Oprah Winfrey, and Bernie Sanders to speak on Bennett’s campus.

Bennett’s campus has been remodeled and expanded over the years, including the remodeling of the Pfeiffer Plant (originally constructed in 1935) into the Journalism and Media Studies building in 2009.

As of 2022, Bennett College is led by College President Dr. Suzanne E. Walsh, has a faculty-to-student ratio of 7:1, is one of only two all-female Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States, and has a study abroad program in addition to the school’s nine major academic programs. Bennett College has grown and changed throughout its existence, but their mission remains “preparing women of color to lead with purpose, integrity, and a strong sense of self-worth.”

Educator Resources:

The Women of Bennett College: Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, ANCHOR: https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/women-bennett-college-unsung-heroes

Unsung Women of the Civil Rights Movement, Carolina K12: https://k12database.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2018/01/UnsungWo...

Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Grades K-8: https://www.ncpedia.org/historically-black-colleges-and-universities-K-8

References:

Bennett College, “About Bennett.” bennett.edu. Bennett College. May 13, 2022. https://www.bennett.edu/about/ .

Bennett College, Factbook 1998-1999. Bennett College, 1999.

Bennett College, 100th Anniversary. Greensboro, NC: Bennett College, 1973.

Favors, Jelani M. “Race Women: New Negro Politics and the Flowering of Radicalism at Bennett College, 1900–1945.” The North Carolina Historical Review 94, no. 4 (2017): 391–430. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45185396.

Moss, Juanita Patience, Tell Me Why Dear Bennett. Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books Inc., 2010.

Additional Resources:

The Belle, Bennett College Historical Yearbooks, Available online courtesy of the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center.

The Bennett Banner, Bennett College Student Newspaper, Available online courtesy of the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center.

Favors, Jelani M. “Race Women: New Negro Politics and the Flowering of Radicalism at Bennett College, 1900–1945.” The North Carolina Historical Review 94, no. 4 (2017): 391–430. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45185396.

Image Credit:

Bennett College, ca. 1922. Photo courtesy of UNC's DocSouth. Available from https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/stowell/ill49.html (accessed May 8, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Wadelington, Charles W.