Blimps over Elizabeth City

by Stephen D. Chalker

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Before the United States entered World War II in December 1941, only one lighter-thanair—or blimp—base existed on the East Coast, in Lakehurst, New Jersey. With the growing possibility of war with Germany, however, the U.S. Navy already had begun to seriously look at its defensive capabilities. High on the list was the protection of shipping and harbors. At the time—in an age before helicopters—the best vehicle to do this job was the blimp. The blimp could hover, fly slowly with convoys for extended periods, and carry the sensors and weapons needed to detect and destroy German submarines. Blimps operating from a base in northeastern North Carolina would be able to protect ships from the Delaware Bay to mid-South Carolina, including in the important Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia. So officials decided to build a new base: Weeksville Naval Air Station outside of Elizabeth City.

Before the United States entered World War II in December 1941, only one lighter-thanair—or blimp—base existed on the East Coast, in Lakehurst, New Jersey. With the growing possibility of war with Germany, however, the U.S. Navy already had begun to seriously look at its defensive capabilities. High on the list was the protection of shipping and harbors. At the time—in an age before helicopters—the best vehicle to do this job was the blimp. The blimp could hover, fly slowly with convoys for extended periods, and carry the sensors and weapons needed to detect and destroy German submarines. Blimps operating from a base in northeastern North Carolina would be able to protect ships from the Delaware Bay to mid-South Carolina, including in the important Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia. So officials decided to build a new base: Weeksville Naval Air Station outside of Elizabeth City.

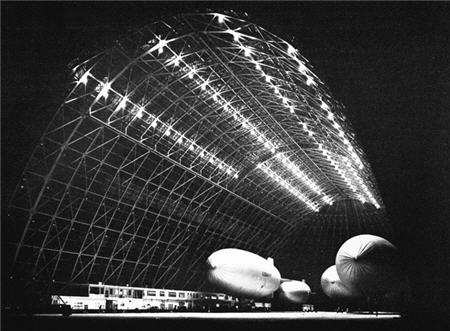

When completed, Weeksville covered 822 acres. It had ten miles of railroad tracks, a steel hangar with space for twelve navy “K” ship blimps, and housing for 700 enlisted personnel and 150 officers. It cost more than $6 million. A second hangar was completed on July 15, 1943; this was the first of seventeen such wooden hangars built in the United States during World War II. The first blimp squadron, called a ZP or Airship Patrol, stationed at Weeksville was ZP-14, established June 1, 1942.

During World War II, blimps from Weeksville escorted ship convoys off the coast and did search and rescue work, often hovering and lowering emergency equipment. The workhorse of the ZP squadrons was the “K,” or “King,” blimp. These nonrigid airships— with no internal frame, unlike dirigibles, such as the Hindenburg, Shenandoah, and Macon—were 252 feet long, and could carry a crew of up to 18. The blimps were armed with fifty-caliber machine guns and depth charges for antisubmarine work. The K ship had endurance at cruising speed (sixty miles per hour) of over thirty-eight hours and a range of twenty-two hundred miles, making it ideal for convoy escort duties. Squadrons generally had six K ships and several smaller training blimps.

On June 10, 1944, the navy transferred squadron ZP-14 to French Morocco in North Africa, and it made the first transatlantic flights by blimps. Squadron ZP-24 replaced ZP14 at Weeksville and continued patrols until the end of World War II, when it was disbanded. Records show that before blimp operations began, one ship was lost to German submarines off the coast of North Carolina every other day. With the start of blimp operations, this number dropped to one ship every two and one half months, and these were lost while not being protected by blimps. In the bigger picture, blimps around the United States escorted 89,000 ships during the war, and not one was lost to the enemy while under their protection.

After the war, Weeksville remained in limited use until mid-1957, with blimps and an early helicopter anti-submarine squadron calling it home. Another interesting use of the blimps in the area was to look for moonshine stills. Crews, though, said they would rather look for submarines. Why? Submarines didn’t shoot at them.

The navy kept a small staff on the base until the federal government sold it to the State of North Carolina in 1964. (Weeksville was used as a test site for things like communication satellites and NASA projects.) In 1966 Westinghouse Electric bought the facility, using the base and hangars for storage and later as a place to build cabinets. TCOM was formed in 1971 as a subsidiary of Westinghouse in Baltimore, Maryland, for building and installing tethered communications (and later surveillance) systems using unmanned, unpowered tethered balloons—basically low-flying communication satellites for developing countries. TCOM, and several airship companies leasing space, used the wooden hangar until August 1995, when a spark from a welder’s torch turned the world’s largest wooden structure into its largest bonfire.

TCOM moved into the steel hangar, converting it back into a blimp facility from a furniture factory. Today with the suspended ceiling removed, the 460-ton doors operating again, and the roof refurbished, this grand old lady of lighter-than-air is back in business. Along with TCOM, Airship Management Services Inc. has moved onto the former base, building and servicing the largest blimps flying in the United States. Every blimp operator in the United States except Goodyear, which has its own hangars, uses TCOM’s hangar for servicing and building blimps. Seventy-eight years later, blimps still fly over Elizabeth City.

At the time of the publication of this article, Stephen D. Chalker was a logistics operations coordinator at TCOM, LP, in Elizabeth City. The owner of an extensive collection of photographs and artifacts related to the Weeksville Naval Air Station, he was writing a book on the topic.

Image credit:

"Night (Interior) Scene at the Steel LTA Hangar, Weeksville. Six airships used for coastal patrol were housed in each hangar."Online at http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Building_Bases/bases-10.html

1 January 2008 | Chalker, Stephen D.