Despite its position as a state capital, in the early 1830s and with a population of barely 2,200, the city of Raleigh was small and underdeveloped and had been struck by a series of fires. One of these took the Capitol building in 1831 and along with it citizens’ collective morale. Without efficient transportation and communication to connect it with the outside world, the capital needed reinvigoration. That reinvigoration came, literally and symbolically, with the arrival of the Tornado, the first steam locomotive to enter Raleigh to inaugurate the state’s newly developing railroad.

The city of Raleigh was unremarkable in the year 1833. Fifty years after its founding, it had barely reached a population of 2,000. Before the implementation of the telegraph beginning in the 1840s and with a landlocked location, communication was slow and goods had to be hauled in exclusively by wagon or stagecoach. A low point was reached on the afternoon of June 21, 1831 when a worker involved, ironically, in work to fireproof the Capitol left a solder pot unattended on the roof, causing a fire. The fire destroyed the building and along with it Canova’s marble statue of George Washington. This demoralizing event would spur on the need for a way to breathe life and hope back into the community.

However, there was debate over the efficacy of retaining Raleigh as the state capital. Fayetteville, having just burned a month prior to the Capitol fire, offered to house the new State House. Some advocated for founding a new town by the Cape Fear River to position the capitol near a port. Raleigh ultimately remained the location for the capital, but necessary precaution was taken for the new Capitol building: it would be built at great cost from stone, costing more than $532,000 at completion, compared to the prior building’s cost of $20,000. On the day the cornerstone of the new building was laid, July 4, 1833, North Carolina’s Governor Swain conducted a meeting to discuss another project to revitalize the area: a railroad.

The railroad was a revolutionary idea in 1833. In her 1922 History of Wake County North Carolina, Hope Summerell Chamberlain conveyed the sentiment of Raleigh’s citizens of their backwardness but also of the hope and excitement of the railroad “sensation”. It promised population growth, rising real estate values, better mail service, travel, and connection with the world, and as one newspaper editorial reported, North Carolina would “no longer be the Rip Van Winkle among commonwealths.” Virginia, Chamberlain recalled, quoting from a Petersburg newspaper editorial, was already excited by the promise of progress of the technological wonder of the railroad: “It is impossible to convey to those who have not witnessed a similar scene, an adequate conception of the pride and pleasure that beamed from every countenance when the Engine was first seen descending the plain, wending her way with sylph-like beauty into the bosom of the town, and, like a conqueror of old, bearing upon her bosom the evidence of the victory of art over the obstructions of nature.”

While the new Capitol was under construction, taking nearly seven years to complete from 1833 to 1840, plans to bring rail to North Carolina were underway, beginning with chartering of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad in 1933 and the Raleigh and Gaston Railroad in 1936 in Raleigh with the sale of stock subscriptions to raise money to build the line. Raleigh saw the development of its first rail transport in 1833 with the construction of a mule-drawn tramway on rails to transport stone for the Capitol from the quarry outside of the city to the construction site. Called the “Experimental Railway”, it was financed by Sarah Polk and described by Moses Amis in 1913 as the beginning of Raleigh’s street cars. This may have inspired anticipation of what was to come on March 9, 1840 with the completion of the Wilmington to Weldon rail line, stretching 161 miles, followed twelve days later by the completion of the Raleigh to Gaston line. On March 21, 1840, reportedly amidst a snowstorm, the Tornado drove into Raleigh.

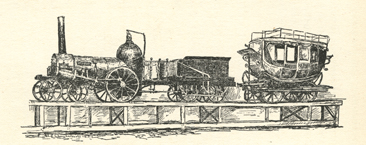

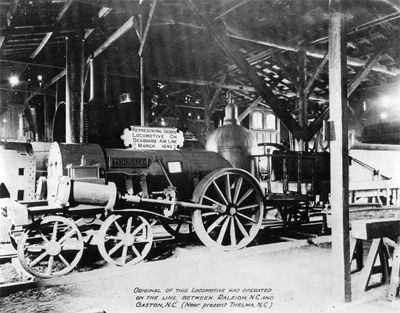

Built by the D. J. Burr Company in Richmond, the Tornado was a technological feat for its time and named for its considerable speed, reportedly being able to clear the 86 miles from Gaston to Raleigh in twelve hours. Other engines from the era were similarly named -- The Tempest, Spitfire, and Whirlwind. Like many engines of its type, it had one driving wheel of about 40 inches in diameter on each side and no cab. The passenger car, according to later drawings, resembled a stagecoach. With the rails and sills made of wood, derailments were common, forcing the crew, passengers, and local farmers to manually to push the vehicle back on the rails and at other times to push the locomotive up a hill. Since the engines ran on wood combustion instead of coal and there was little fuel storage on the engine, when fuel ran out, as Moses Amis reported, an engineer would find a nearby farmer’s fence, take what he could from it, and use the spare wood to get the train to the station. Despite these shortcomings, The Tornado was the promise of economic, technological, and cultural development that would occur rapidly in the 1840s and 1850s.

The concurrent completion of the rail line, arrival of the locomotive, and completion of the Capitol building were celebrated in an event known as “The Three Days of Raleigh.” Taking place over three days from June 10-12, 1840, it unveiled the new State House, the Raleigh Gaston Railroad, and the Tornado. People traveled from across the state and as far as Richmond, Virginia for the spectacle. The first night was commemorated with a banquet held in the new freight depot. The evening activities were illuminated by colored lanterns hanging from the trees of Capitol Square and Fayetteville Street, and events included, according to Hope Summerwell Chamberlain, "jollification, speechification, illumination, and barbecue." During the day visitors took rides on the Tornado. The new State House was also on display. Chamberlain commented on the apparent grandeur of the building and beauty of the local stone: “It is somewhat translucent, having the quality, more than any other stone in the State, of reflecting a different color under every changing sky which looks down upon it. When snow is on the ground, in the glow of a winter sunset, it has a lovely bluish cast.“

The consensus on the newly finished construction and railroad was overwhelmingly positive. North Carolina had spared no expense in launching this next chapter of its history and had rebranded itself as a part of the modern world. State government and business leaders had taken a risk in the promise of railway transportation and decision to rebuild the capital. It was a significant step in the effort toward internal improvements in antebellum North Carolina and conveyed the sense from its chroniclers of triumph over the defeats of the prior decade.

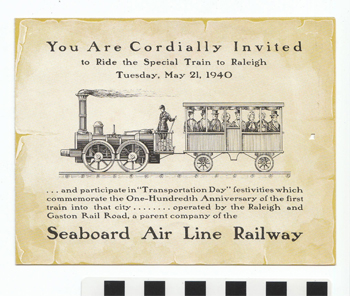

The original of Raleigh's Tornado no longer exists. The engine was reportedly captured in 1865 by Union troops during the Civil War. A replica was built (or possibly rebuilt) in 1892 and used for the Raleigh Centennial Exposition. Today that replica survives at the Historic Depot and Train Museum in Hamlet, NC and in period drawings and photographs. On March 21, 1940, Raleigh celebrated the centennial of the historic completion of the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad and the historic arrival of the Tornado. Invitations and tickets to ride a replica of the train were sent to descendents of passengers of the inaugural train trip, and the reverse of the ticket included an excerpt of the event from the March 21, 1840 Raleigh Register describing the sounds of "PHIZZZZ" and "HUZZA" and the "magnificent enterprise" of the Tornado, unimaginable to the prior generation.