The sudden death of U.S. senator J. Melville Broughton on 6 Mar. 1949 caught North Carolinians by surprise and set the stage for a momentous political brawl. The task of appointing Broughton's successor fell to Governor W. Kerr Scott, a maverick in state politics. Seeking to strengthen his hand, Scott launched a campaign to find a successor to Broughton favorable to his own liberal political agenda and sympathetic to the national Democratic policies of President Harry S Truman.

After an inordinate delay in naming a successor, Scott's decision produced the most explosive surprise in North Carolina's modern political history: Scott named Frank Porter Graham, the 62-year-old president of the University of North Carolina and considered "the most renowned southern liberal of his time." Scott chose Graham because he was not a lawyer, had never sought political office, and was recognized as a great humanitarian who cared about the dispossessed. Graham's friends and admirers believed him to be the noblest of North Carolinians-an educator who had spent his life in selfless service to others, whose voice on such difficult matters as race relations and social policy was enlightened and progressive. Graham's adversaries judged him to be a liberal dreamer, a person of unsound judgment who was hostile to the beliefs and mores of the state and whose career had been marred by association with disloyal organizations, most notably in matters of race and politics.

When Graham agreed to run for a full term in 1950, the attacks on him began. Radio commentator Fulton Lewis Jr. disclosed that the Security Board of the Atomic Energy Commission had recently denied Graham a top-secret security clearance because it questioned the soundness of his judgment and some of his political associations. The board's decision was overturned by the full commission, but the revelation was an ominous harbinger of things to come.

Graham, despite his controversial past, had substantial political strengths, including the strong support of the Scott organization, the Truman administration, organized labor, and Jonathan Daniels, editor of the Raleigh News and Observer. His Democratic primary challengers included Pinetown pig farmer Olla Ray Boyd and former U.S. senator Robert R. "Our Bob" Reynolds, although neither emerged as a serious threat. Graham's most formidable opponent, Raleigh attorney Willis Smith, entered the fray in February 1950. A former Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives and president of the American Bar Association, Smith was part of the conservative "plutocracy" that had governed North Carolina since the 1930s.

From the outset, Smith went on the attack. He denounced socialism and communism, implying that Graham was unaware of the threat posed by either. He opposed the Federal Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) as an invasion of state rights. Smith accused Graham of supporting the FEPC and, as a member of Truman's Civil Rights Commission, of desiring to end statutory racial segregation. Graham, the nonpolitician, responded meekly to the attacks and solicited neither votes nor campaign contributions. He did correctly note that he opposed the FEPC and the use of federal force to compel integration. Smith continued to paint Graham as a "pink" and a muddle-headed academic who had long associations with groups named by the U.S. attorney general as subversive. Graham refrained from personal attacks, but his office slammed Smith as a rich corporate lawyer who was unconcerned about the needs of working-class North Carolinians.

Just prior to the first primary vote, a new emphasis on racial issues emerged with incendiary handbills disseminated across the state. Especially inflammatory was the charge that Graham had appointed a young African American, Leroy Jones, to West Point. The charge was false, but the racial issue had now been broached.

When the votes were counted in the first primary, Graham received 303,605 (48.9 percent) to Smith's 250,222 (40.5 percent). Reynolds and Boyd garnered 10.6 percent. Graham had come agonizingly close (5,634) to a clear majority but had failed to win the election outright, and Smith was entitled to call for a runoff. While Smith considered his course, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down three major decisions affecting southern race relations. The most important for North Carolina was Sweatt v. Painter, in which the Court ordered the University of Texas to integrate its law school. These decisions marked the beginning of the end of all-white public education in the South and set off racial alarms throughout the region. A young Jesse Helms and other Smith supporters broadcast advertisements calling on people to rally at Smith's residence, imploring him to aggressively attack Graham's liberalism. Smith quickly obtained the necessary funds and the enthusiastic support required for a second primary.

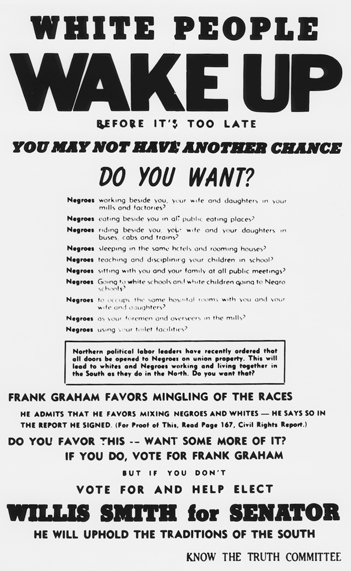

Having called for a runoff, the Smith forces went on the offensive, declaring Senator Graham a communist sympathizer and charging that blacks were guilty of "bloc-voting" for Graham in the first primary. One flyer, titled "White People Wake Up," claimed that Graham favored "race-mingling" in the work place, hotels, restaurants, and schools. The result was a racial pandemic. Opponents verbally attacked Graham on the stump, and his backers received threatening telephone calls.

In an astounding turnaround, Smith won the second primary 281,114 to 261,789, mainly because white voters in the east abandoned Graham. Graham had been rejected in a campaign of savage intensity by those he seemed to care about the most-poor members of the working class and farmers. Smith proponents succeeded in using communist and race issues to defeat a candidacy sympathetic to both racial and economic equality. The campaign was a triumph of tradition over liberalism and undermined North Carolina's image as progressive on race issues. In the general election in November, Smith defeated Republican E. R. Gavin 364,912 to 177,753.