See also: Camp Meetings; Mourner's Bench; Great Awakening; Religion

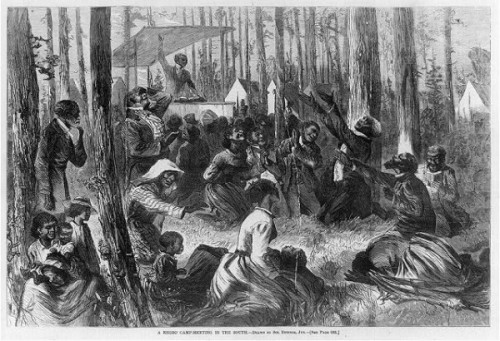

The term "revival" has been used to describe what happens in local congregations when people manifest a deep religious fervor that may be accompanied by a large number of religious conversions. Early revivals often took place in the woods, near a river or a stream. People brought tents and food and slept outdoors during the event. These gatherings were also social events, when people saw friends and family members they might not have seen for a long time. Revivals usually began with singing, followed by a powerful and emotional sermon. Charismatic ministers preached a message of personal salvation, or a new birth. The minister then would walk among the people, which was something ministers had never done before. These very emotional meetings lasted for hours. People were taken over by what was called "the exercises." As part of their conversion experience, people would sometimes dance, shake, laugh, bark, or fall to the ground.

Such revivals occurred in New England and the Middle Atlantic colonies during the period known as the First Great Awakening (1730-60). Among such groups as Separate Baptists in New England, local revivals continued in scattered communities long after this period. Several families of these Separate Baptists, led by Shubal Stearns and Daniel Marshall, migrated south and finally settled on Sandy Creek in Guilford (now Randolph) County in 1755. There they organized a church, and soon they also began to preach in their exuberant style in other communities over a wide area, winning converts and organizing more churches. In the 1770s and 1780s, Methodist itinerants made inroads into North Carolina, bringing their own brand of evangelical religion to the backwoods and hamlets of the state. Presbyterians, who had earlier moved into the Piedmont, were sometimes visited with revivals like the one sparked by James McCready in Guilford County prior to his removal to Logan County, Ky., in 1797.

Prior to 1800 there was growing concern among Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians about a general decline in the religious and moral climate of the South and the entire nation. The popular press was disseminating the views of deists like Thomas Paine; people were migrating in large numbers west of the mountains in search of cheap land and quick wealth; and the churches in the East were losing members and could not keep up with the rapidly growing population on the frontier of America.

In 1800 the first wave of the Second Great Awakening began on the frontier in Kentucky and Tennessee with the tried and proven method of revivalist preaching by James McGready, who was soon joined by others, including Presbyterians and Methodists. The revival soon spread into Virginia and the Carolinas as ministers who had longed to see revival in their own churches journeyed to the frontier to witness for themselves the remarkable effects of this revival. Using the same technique in the churches back east, revivalists soon discovered that similar results could be expected though they would not always be accompanied by the unusual physical manifestations seen in the frontier revivals. This Great Revival, as it became known in the South, was to have a lasting impact on the shape of religion in the region.

Revivals continued to be a characteristic feature of North Carolina churches throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. These revivals, unlike the more spontaneous revivals during the First Great Awakening, became a technique for winning converts and giving new life to the churches. More and more preachers sought to bring about a revival by utilizing means that had demonstrated their effectiveness in attracting crowds and persuading many to "make a decision for Christ," all of which was possible because of a shift in the underlying theology of the churches. On the frontier, camp meetings became the vehicle for revivals, especially among the Methodists, who placed great emphasis on the religion of the heart and were inclined to impose few restraints on emotions. Baptists and Presbyterians also made use of camp meetings but more often preferred to stage revivals either in church buildings or auditoriums that could accommodate large numbers.

Although more popular revivalists such as Dwight L. Moody and Billy Sunday were to be found in the North, the South had its share of effective though lesser-known figures as well as some famed preachers. Beginning in the late 1940s Billy Graham, a native of North Carolina who was to become perhaps the best-known evangelist of the twentieth century, burst upon the scene, using the latest means of communicating the gospel. His evangelistic work in this country and abroad won him recognition beyond that enjoyed by any of his peers.