Mount Mitchell, at 6,684 feet above sea level, is the highest point in the eastern United States. Located in the Black Mountain range of the Southern Appalachians, it is part of an intricate mountain system featuring some of the oldest and most complex geological formations on earth. Although the Black Mountains are only about 15 miles in length, the major peaks average well above 6,000 feet in elevation.

Anthropologists believe the earliest inhabitants in the vicinity of Mount Mitchell settled there some 13,000 years ago. At the time the first white explorers and settlers arrived, the area was a hunting ground for the Cherokee Indians. Following the American Revolution, however, the Indians were pushed westward from the area by a relentless tide of white settlers.

Perhaps the first European to ascend Mount Mitchell was French botanist André Michaux, who collected plant specimens in the Black Mountains in 1789. Michaux also ascended Grandfather Mountain, mistakenly proclaiming it to be the highest peak in the Appalachians. Another botanist who explored the area was John Fraser, for whom the Fraser fir was named. The Fraser fir grows naturally along the Black Mountain summits.

The first person to scientifically study Mount Mitchell and the Black Mountains from the standpoint of physical geography was Professor Elisha Mitchell of the University of North Carolina. In 1835 Mitchell took barometric pressure readings from the major peaks of the Black Mountain range to determine their altitudes. From his observations Mitchell determined that the highest point in eastern America was in the Black Mountains rather than in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, as was previously believed. Mitchell returned to the Black Mountains in 1838 and again in 1844 for further study.

In the mid-1850s, Mitchell became embroiled in a bitter dispute with a former student, Congressman Thomas Lanier Clingman, over whether or not Mitchell had correctly identified the highest peak in the Black Mountains. The dispute escalated until the summer of 1857, when Mitchell returned to the Black Mountains to try to verify his earlier scientific findings. In the process of trying to obtain corroborative evidence, Mitchell was hiking across the northwest side of Mount Mitchell when he slipped and fell from a cliff near a 40-foot waterfall, hitting his head and drowning. The location of his death is known today as Mitchell Falls.

The controversy, which did not die with Mitchell, subsequently became entangled further in the politics of the day. Zebulon B. Vance was one of Mitchell's most vocal defenders. Clingman may have won the public debate while Mitchell lived; however, after the tragic accident, the beloved professor was vindicated as far as Clingman's political enemies and the people in general were concerned. Mitchell's body, having been interred in Asheville, was reinterred a year later at the summit of the mountain that continues to bear his name.

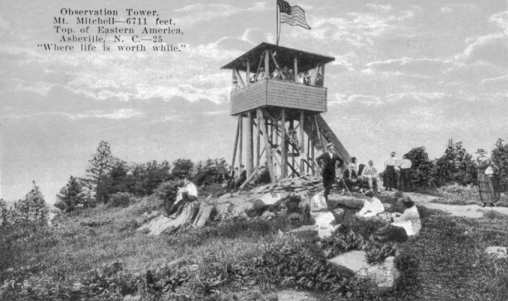

In 1939 the Blue Ridge Parkway was completed from N.C. 80 to Black Mountain Gap. The following year the state acquired and improved the toll road from the parkway to Camp Alice. As a result, the public was given toll-free motor road access to Mount Mitchell for the first time. A new road (present-day N.C. 128) from the parkway was constructed to within a short walk of the summit in 1948. Two years later, the Blue Ridge Parkway was completed to Asheville, resulting in more than 200,000 people making their way to Mount Mitchell in 1950. A new observation tower was completed in 1960 to accommodate the increase in visitation.

In the 1970s legislation proposing to make Mount Mitchell a national park was passed by Congress; however, there was considerable local opposition and the idea was dropped in 1979. In the 1980s and 1990s, an environmental problem developed that threatened Mount Mitchell State Park as well as other peaks in the Southern Appalachians approximately 6,000 feet elevation and above. The balsam forests at the mountain summit were attacked by an insect called the balsam woolly aphid. Acid rain and other atmospheric pollution from industrial activities in other areas of the country began taking a toll on the balsams also. By the mid-1990s practically all of the trees at the summit had died. A number of scientists set forth the theory that the trees were weakened by pollution, therefore making them susceptible to insect attack. Although young seedlings on the summit appeared to be healthy, it was questionable as to whether the balsam forests on Mount Mitchell and the other Black Mountain summits would return or not.

In 1993 Mount Mitchell was designated as an International Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This designation added Mount Mitchell to an elite group of sites throughout the world that are protected for the purpose of discovering the solutions to problems of conservation, sustainable development, and other issues.