Colored Merchants Association

"Challenging the Chain Stores"

by Dr. Lisa Tolbert

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2007.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

For two months in the spring of 1929, a group of African American grocery store owners in Winston-Salem organized public lectures, meetings, exhibits, and food tastings that attracted large audiences and national attention. What was all the fuss about?

For two months in the spring of 1929, a group of African American grocery store owners in Winston-Salem organized public lectures, meetings, exhibits, and food tastings that attracted large audiences and national attention. What was all the fuss about?

The grocers were joining a new cooperative business group called the Colored Merchants Association (CMA), which had begun in Alabama. On April 17 they announced in a local newspaper an ambitious plan to create “a movement looking towards the salvation of the Negro independent grocery stores, through cooperative buying and teaching the lesson and value of advertising.” National Negro Business League leaders promoted the grocers’ efforts as a national model for African American businessmen working in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

To understand why the Winston-Salem activities got so much attention, it is important to know about changes in the grocery business in the 1920s and about the impact of segregation on African American store owners and shoppers.

In the 1920s, segregation laws and customs restricted public activities based on race. Signs marked such spaces as public bathrooms, train station waiting rooms, or sections in movie theaters for “white only” or “colored only.” (The terms colored and Negro were widely used for nonwhites and for persons of African descent, respectively, in the early twentieth century.) Despite the restrictions, African Americans started successful business communities and created vibrant neighborhoods in the segregated South. Local grocery stores became the most common small businesses run by Black merchants. That’s a big reason why the Winston-Salem grocers made such an impact. In 1929 the city directory listed 373 grocery stores. African Americans operated more than 30 percent (128 of them), making up by far the largest group of Black businessmen there. These store owners faced new challenges because of important changes in the retail trade.

Chain stores—such as Sears, Roebuck and Company, F. W. Woolworth, and the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P)—grew a lot in the early 1900s. A chain is a company that runs many stores in different places, operating under the same name and selling the same merchandise. Chain stores created new ways to sell groceries—which meant stiff competition for smaller stores.

Hundreds of small, independent grocery stores dotted downtowns and neighborhoods throughout southern cities and towns of the early 1900s. Most grocers, white and Black, owned one store that served the neighborhood where they lived. Customers walked daily to their neighborhood store to shop or phoned in orders for delivery. By the 1920s, however, new chain stores began to attract more and more customers with low prices and modern interiors.

During the early 1900s the number of grocery chains in the United States had doubled. These chains kept growing and adding stores. For example, the largest and most successful grocery chain, A&P, operated a few hundred stores in the Northeast during the first decade of the twentieth century. It grew to more than eleven thousand stores nationwide in the 1920s. With fifteen locations in Winston-Salem in 1929, A&P owned more stores in that city than any grocer.

Because A&P ordered more numbers of an item than a single grocer did, wholesalers sold products to the chain at lower prices. The chain stores passed the savings along to the customer, selling many brand-name products at a lower price than the independent grocer could afford. A&P made sure that Winston-Salem customers knew about its bargains by advertising regularly in the local newspaper. Most independent grocers didn’t spend money to advertise. They relied on neighborhood foot traffic. Independent grocers, white and Black, worried more and more about the chains.

African American grocers in Montgomery, Alabama, had decided to work together to compete. A. C. Brown, a successful grocer in that city for twenty years, persuaded fourteen grocers to combine their buying power and place orders with wholesalers together. This way, they got lower prices to stock their stores. This cooperative, called the Colored Merchants Association, operated as a kind of voluntary chain. The idea was to pool money for buying products and advertising, and to educate African American merchants about modern business practices. Goals included increasing stores’ profits by improving accounting methods; modernizing store interiors to provide a better shopping experience; and creating greater awareness of the buying power of African Americans.

Winston-Salem played an important role in the history of the CMA because the National Negro Business League chose it as the first place to expand the organization outside Alabama. Winston-Salem’s large number of successful Black grocers provided strong leadership in the African American business community. They had already created a merchants’ association that could help CMA leaders.

In the spring of 1929, representatives of the National Negro Business League—which Booker T. Washington had started in 1900 at Tuskegee Institute—traveled to Winston-Salem to help the African American grocers organize. Winston-Salem Teachers’ College (now Winston-Salem State University) played a major role in publicizing the CMA. The college hosted lectures to inform shoppers, accounting workshops for store owners, and events such as a public introduction of nationally advertised products. To teach buyers about new kinds of brand-name products, home economics teachers served Welch’s grape juice punch with Nabisco wafers and Best Foods mayonnaise with Sunshine crackers. CMA leaders remodeled the grocery store of James A. Ellington, at 723 East Seventh Street, into a model store, based on a display at a national grocers conference. On opening night, 583 shoppers crowded the small space to get a look.

Twenty-four merchants joined the CMA in the first organizing campaign in Winston-Salem. They soon reported record sales. The idea was so successful that by the early 1930s, the CMA had spread to larger cities in the North and the South, including Birmingham, Atlanta, New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression of the 1930s put new pressure on small businessmen, and the merchants of the CMA fell on hard times. By 1932 Ellington had closed his model store on Seventh Street, and the Winston-Salem city directory now listed only seventy-nine African American grocers—a little more than half of those listed in 1929, when the CMA expanded to Winston-Salem. By 1936 the CMA went bankrupt. Chain stores and supermarkets increasingly replaced the small grocer after the 1930s.

The history of the CMA, though, shows the activism of African American merchants and communities in the segregated business environment of the early 1900s. The cooperative organization effort in Winston-Salem was larger than an effort to compete with chain stores. Together, merchants, educators, and housewives used grocery stores as a tool to teach improved business methods, show consumers new products, and raise awareness about African American buying power.

At the time of this article’s publication, Dr. Lisa Tolbert was an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, teaching courses in American architecture and cultural history. She was working on a book exploring how changes in spatial design reshaped social practices in grocery stores of the segregated, urban New South.

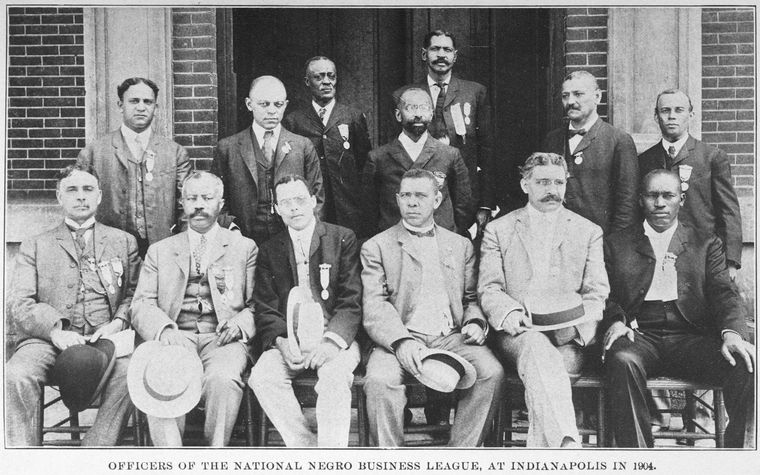

Image credit:

"Officers of the National Negro Business League in Indianapolis, 1904." Image ID: 1229313. Online in the New York Public Library Digital Gallery at http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?1229313.

1 January 2007 | Tolbert, Lisa