Portions excerpted from Guide to Research Materials in the North Carolina State Archives: State Agency Records.

See also: Eugenics board; Eugenics legislation in North Carolina

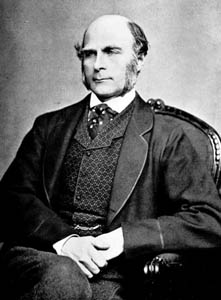

The eugenics movement of the early twentieth century grew out of the research and writings of the English scientist, Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911). Galton, the half-cousin of Charles Darwin, had a variety of interests included psychology, genetics, and statistics. Among his beliefs was the idea that government intervention could help promote the biological improvement of humans.

As part of the movement many states, including North Carolina, enacted laws that allowed sterilization of the "mentally diseased, feeble minded or epileptic." In 1929, the North Carolina General Assembly authorized the governing body or executive head of any penal or charitable public institution to order the sterilization of any patient or inmate when such an operation was deemed to be in the best interest of an individual or for the public good. Additionally, the county boards of commissioners were authorized to order sterilization at public expense of any people with mental illnesses resident upon receiving a petition from the individual's next of kin or legal guardian.

Each order for sterilization was required to be reviewed and approved by the commissioner of the Board of Charities and Public Welfare, the secretary of the State Board of Health, and the chief medical officers of any two state institutions for people with mental illnesses. A medical and family history of the patient or inmate was attached to the order to provide information and guidance for the reviewers.

In 1933 the General Assembly created the Eugenics Board of North Carolina to review all cases involving the sterilization of people with mental illnesses, or epileptic patients, inmates, or non-institutionalized individuals. The five members of the board included the commissioner of the Board of Charities and Public Welfare, the secretary of the State Board of Health, the chief medical officer of a state institution for people with mental illnesses (appointed by the other board members), the chief medical officer of the State Hospital at Raleigh, and the attorney general.

In hearings that involved patients or inmates in a public institution, the executive head of that institution (or his representative) acted as prosecutor in presenting the case to the board. Hearings that concerned non-institutionalized individuals were prosecuted by the county superintendent of welfare or another authorized county official. Along with the petition for a hearing, the prosecutor provided a medical history signed by a physician who was familiar with the case and a social history addressing whether the person was likely to produce offspring.

A copy of the petition was sent to the individual and his or her next of kin or guardian. When the inmate, patient, or other individual could not defend himself or herself at the hearing, the next of kin, guardian, or county solicitor represented the individual and defended that person's rights and interests. The county superior court could appoint a guardian if necessary. Individuals could also be represented by legal counsel during the hearing.

Factors to be considered by the board included whether the operation seemed to be in the best interest of the individual's mental, moral, or physical health; whether it would be for the public good; and whether it was likely that the individual might produce children with serious mental or physical problems. Orders for sterilization had to be signed by at least three members of the board and returned to the prosecutor. Mentally competent individuals, at their own expense, could select their own physician for consultation or for an operation. A decision by the board could be appealed by the individual or in his or her behalf to the county superior court and further appealed to the state's supreme court. A successful appeal precluded any further petition for the sterilization for one year unless specifically requested by the individual, or by his or her guardian or next of kin.

In 1937 the General Assembly authorized any state hospital, at the discretion of the superintendent, to provide temporary admission for people with mental illnesses, people with developmental disabilities, or epileptic for whom the Eugenics Board had authorized sterilization. The regular or consulting staff of the hospital could then perform the operation. These hospitals were authorized to charge the appropriate state institution or county for the operation and expenses.

Under the Executive Organization Act of 1971, the Eugenics Board of North Carolina was transferred to the newly created Department of Human Resources (DHR). Although the board retained its statutory powers and actions regarding sterilization proceedings, the board's managerial and executive authority was vested in the secretary of the DHR, a cabinet-level officer appointed by the governor.

Under the Executive Organization Act of 1973, the Eugenics Board became the Eugenics Commission. The following five members of the commission were to be appointed by the governor: the director of the Division of Social and Rehabilitative Services of the DHR, the director of Health Services, the chief medical officer of a state institution for people with mental illnesses, the chief medical officer of the DHR in the area of mental health services, and the attorney general.

In 1974 the General Assembly transferred to the judicial system the responsibility for any sterilization proceedings against persons suffering from mental illness or mental retardation. In 1977 the General Assembly formally abolished the Eugenics Commission, and the act to repeal the original laws (G.S. 35-36 through 35-50) was finally passed in 2003.