Trails and Trading Routes

Marks on the Land We Can See: Routes of Carolina's Earliest Explorers

by Tom Magnuson

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2007; Revised October 2022.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

In 1673 Gabriel Arthur—a young indentured servant from the neighborhood of modern Petersburg, Virginia—went to live in the Appalachian Mountains with Indians, probably those we call "Cherokee." In the year that Gabriel, likely still a teenager, lived with these people west of Asheville, he went raiding with them. He traveled north to raid the Shawnee on the Ohio River, and he traveled south to raid Spanish mission Indians in Florida. His travels, all done in one raiding season, were made on foot.

Look at a map, and try to imagine walking from the Asheville area to the Ohio River and then down to northern Florida.

Explorers come in many forms with many motives for exploration. Some are just curious, and some just adventurous. Some, like young Gabriel, are ordered into the wilderness by their owners. Some are desperate to escape one thing or another. European soldiers, traders and raiders, debtors, freedom-seeking indentured servants, and freedom-seeking enslaved people all used Indian trade routes to find their way into the unknown parts of America and make those parts known. The first of these explorers traveled on American Indian trading paths.

Long before Europeans showed up, American Indians maintained extensive networks of trading paths. These footpaths connected neighboring villages, broadly scattered nations, and effectively the entire continent. We know this from the trade goods found in archaeological sites. For example, archaeologists have found obsidian "points" in Ohio, and the nearest obsidian (volcanic glass) is found in Idaho. And, of course, the basic foods grown by Indians in the area of North Carolina developed in modern Latin America far, far to the south.

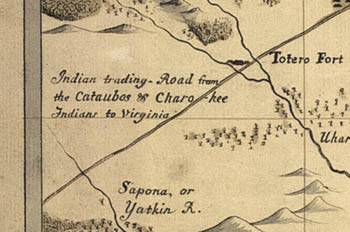

Some of these ancient pathways later gained English names and a good deal of fame. What came to be called the Great Wagon Road was once the Warriors Path, a well-known trail used by Iroquoian and Siouan raiders traveling between upstate New York (the Iroquois homeland) and Sioux lands centered on the Catawba villages near modern Charlotte. There also was the Occaneechi Path, a name given to a number of different routes leading to and from Occaneechi Island (modern Clarksville, Virginia). And the road now noted with historic markers all over North Carolina, now known as the Trading Path, existed early on. It appeared on maps as early as 1733.

Most of these named trails, though, didn't exactly follow the original footpaths. That is because wagons move differently than horses, and horses move differently than people. People are really quite agile when compared to horses and wagons. Horses have bad brakes, and when they go downhill, they often lose footing. So horse paths frequently differ from human paths around steep slopes. Of course, wagons have even more difficulty with slopes. Even in Roman times, road builders knew that a slope that would carry wagons could have no more than a 5 percent grade (five feet of descent for every one hundred feet of forward movement) to keep wagons from "running away."

Most of these named trails, though, didn't exactly follow the original footpaths. That is because wagons move differently than horses, and horses move differently than people. People are really quite agile when compared to horses and wagons. Horses have bad brakes, and when they go downhill, they often lose footing. So horse paths frequently differ from human paths around steep slopes. Of course, wagons have even more difficulty with slopes. Even in Roman times, road builders knew that a slope that would carry wagons could have no more than a 5 percent grade (five feet of descent for every one hundred feet of forward movement) to keep wagons from "running away."

What few physical facts we know about the old Indian trade and war routes that European explorers of the New World regularly used, we know from traces still visible today. We know, for example, that the trails followed the "military crest" of the ridge. That is, they ran alongside, but not on, the ridge tops. That way, as a person moved along a trail, only those on one side of the ridge could see him or her. And from measuring remnants of their old trails—some of them hundreds of years old—we know that American Indians did, in fact, discipline themselves to walk heel-to-toe in single file, leaving the smallest possible marks on the ground. Apparently, the first rule of s urvival in prehistoric times was not to be seen.

urvival in prehistoric times was not to be seen.

Shortly after arriving in America, Europeans wanted to start trading with Indians in the backcountry. They hired Indian porters to carry their trade goods. Men, women, boys, and girls all served as porters, because the Indians around the South did not have draft animals like horses or mules. As soon as you were able to tote a load, you became a worker for the tribe. Indians had used porters to carry trade goods for many centuries, and a porter's typical load was up to eighty pounds. It was the way trade was done.

But, soon after Europeans established trade with tribes in the backcountry, because of economies of scale, packhorses replaced porters. Resentment about being put out of work by horses, and resistance to changing a tradition as old as portering, at least in part, contributed to the 1676 outbreak of violence known to history as Bacon's Rebellion. After Bacon's Rebellion, almost all cargo moved on horseback, until wagons replaced packhorses in the 1720s and 1730s. The collision between the porters and packhorse men was repeated when wagoners replaced packhorse men as the knights of the road. But that is a different story—the story of settlement, not exploration.

By 1730, settlement had come to the backcountry. The arrival of wagons tells us that the age of exploration and frontier mostly had passed into memory. We can share in the memory of those years before settlement by finding, preserving, and studying the old trade routes. Old roads, trails, and paths help us imagine times gone by. Take a look at the old roadbed shown above. Spend a moment imagining what you would have seen, heard, and smelled standing by this road two hundred years ago when it was still in use.

Traders exploring for new markets and new products in the remote backcountry found and traveled along the footpaths of the people who had come before—the Indians, freedom-seeking enslaved people and escaped indentured servants, the curious, the desperate, the invisible first people of the frontier.

Young Gabriel Arthur saw no wagon roads when he ran through the country with his American Indian hosts. He and the others like him, the first European travelers and explorers, saw only footpaths.

Additional Resources:

NC Museum of History, Timeline of American Indians in North Carolina: http://www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/collateral/articles/F05.time.line.pdf

The Way We Lived in NC: The Great Wagon Road: http://www.waywelivednc.com/before-1770/wagon-road.htm

Image Credits:

Cowley, Herman. 1737. “A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina drawn from the Original of Colo. Mosely's,” ID: MC.150.1737c; MARS Id 3.3.630. North Carolina Maps. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,1245.

1 January 2007 | Magnuson, Tom