Footpaths

See also: Great Trading Path; Green's Path.

Footpaths have existed in North Carolina since early colonial days, when roads were not well maintained and  traveling by foot was the best way to go from place to place. Long walks were uncommon, although some Moravians actually walked from Bethlehem, Pa., to Wachovia, N.C.-a distance of about 400 miles that usually required more than a month to complete.

traveling by foot was the best way to go from place to place. Long walks were uncommon, although some Moravians actually walked from Bethlehem, Pa., to Wachovia, N.C.-a distance of about 400 miles that usually required more than a month to complete.

There were paths between farms as well as from farms to gristmills, churches, crossroads stores or taverns, racetracks, neighborhood schools, and the nearest villages. Numerous paths to a militia district often led to the muster grounds on which troops regularly drilled. Until the introduction of the railroad, many troops at war generally moved by foot along paths that frequently offered the most direct and secure routes. Streams were crossed by footlogs or, if they were shallow, by boulders at appropriate intervals. Footpaths beside or across a field were not disturbed during plowing. Often the topsoil in fields eroded, while undisturbed paths remained firm and well packed; this resulted in a path sometimes being elevated a foot or more higher than the adjacent field. As late as World War I, it was said that there was a nearly straight footpath from Chapel Hill to Raleigh used by university students for weekend visits home.

Eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century deeds and wills sometimes mentioned paths by name. John Bryan's will, made in Edgecombe County in 1734, made note of land that he owned "on the Indian path." A Bertie County will from 1751 referred to "Carter's Path" between the homes of William Yeates and Bryan Hare. A journal kept by the Moravians in 1772 indicated that a path from the site of the Battle of Alamance was so poorly marked that a traveler walked a dozen miles in the wrong direction before discovering the error. In 1794 a deed stated that Dr. Charles Pasteur owned 737 acres in Halifax County on "Steel's Path."

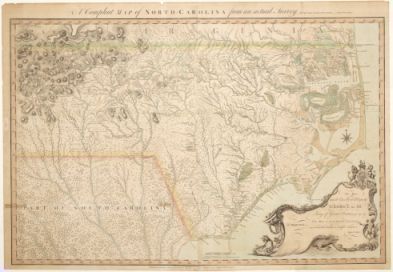

Paths were frequently depicted on eighteenth-century maps. Edward Moseley's A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina (1722) labeled the trails of the Nansemond and Meherrin Indians in eastern Bertie County. John Collet's A Complete Map of North Carolina (1770) included the "Path to the Cherokee Nation," "Crafford Path," "Green's Path," "the Trading Path," and "the Western Path." On his An Accurate Map of North and South Carolina with Their Indian Frontiers (1775), Henry Mouzon showed eight distinct paths, several extensive in length. They were labeled "the path from Cahuitta," "Crawford Path," "Lower Path," "Lower Trading Path," "Path from Oalcsoskee," "Old Trading Path," "Trading Path," and "The Western Path." This map was used by both American and British troops in North Carolina during the American Revolution.

Image Credits:

"A Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey," 1770. John Collett. Image courtesy of North Carolina Maps, UNC Libraries. Available from http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/467 (accessed September 27, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Powell, William S.