See also: Public Libraries; Library, State; Library history: NC Digital Collections

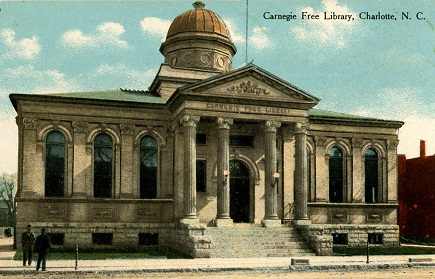

Between 1886 and 1923, industrialist Andrew Carnegie and the Carnegie Corporation donated funds for more than 1,600 public library buildings in the United States. Ten of those libraries were constructed in North Carolina. Charlotte was the first North Carolina city to apply for Carnegie funds; its application for $25,000 was approved in 1901. Greensboro applied next, in 1902, and Winston-Salem (1903), Rutherford College (1907), Hendersonville (1911), Andrews (1914), Murphy (1916), Durham (1917), and Hickory (1917) followed. In 1915 Charlotte received an additional grant of $15,000 to add a children's room and an auditorium. After several false starts, Greensboro was given a second grant in 1922 to construct a branch for African Americans.

Carnegie's philanthropy spurred the creation and institutionalization of public library service in many communities. However, most towns eventually outgrew their original Carnegie buildings. In North Carolina, the period after World War II saw an expansion of collections and services that forced many of the nine towns with Carnegie libraries to build new facilities. The Carnegie libraries in Andrews, Charlotte, and Rutherford College were torn down, as was the white Carnegie library in Greensboro. Greensboro's second Carnegie library is now part of the Bennett College campus. The Carnegie buildings in Durham, Hendersonville, Hickory, Murphy, and Winston-Salem still stand, but none is used as a library.