17 Feb. 1770–7 Oct. 1818

David Stone, governor, congressman, senator, legislator, and justice, was born in Bertie County of English ancestry. He was the son of Zedekiah and Elizabeth Shivers (or Shriver) Hobson Stone. His father, who moved to North Carolina from Massachusetts before 1769, was active in commercial, agricultural, and political ventures during the American Revolution. David Stone graduated with first honors from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1788. He studied law under William R. Davie and was admitted to the bar in 1791.

As a Federalist he was elected to represent Bertie County in the 1789 convention at Fayetteville, which ratified the U.S. Constitution on behalf of North Carolina. The following year he was elected to his first term in the North Carolina House of Commons. Serving until 1795, he displayed an interest in internal improvements and advocated improved education. On leaving the house, he was a superior court justice from 1795 to 1798. In 1798 Stone won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and there was appointed to the first standing committee on Ways and Means. At the same time he made his first crucial political decision when he switched from the Federalist to the Republican party and supported Thomas Jefferson for president in 1800. Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1800, he upheld the Republican party except for his votes opposing the Embargo Acts. After completing his term in the Senate, he returned to the North Carolina Superior Court for two more years (1806–8).

The General Assembly elected Stone governor in 1808 and 1809. In that office he recommended legislation to improve higher and lower educational facilities, to nurture infant industries, and to increase the salaries of judges. Negotiations on the boundary dispute between North Carolina and South Carolina, the controversy over the Granville claims, the establishment of a state bank, and military matters were significant issues during his two terms as governor.

Controversy began to surround him after his election to the House of Commons in 1811. Stone supported legislation to improve navigation of the state's rivers and led the floor fight to repeal the Electoral Act of 1803, which provided for the election of presidential electors by the district system. The Electoral Act of 1811 required that electors be chosen by the General Assembly. The repeal of the act of 1803 was bitterly contested, and Stone sponsored a new act in 1812 that called for the election of the electors by the voters of North Carolina.

The second crucial phase of his political life began with his election to the U.S. Senate in 1812. Stone refused to support the War of 1812, the embargo, the direct tax, diplomatic appointments, or the curtailment of the illegal shipping trade. As a result of his opposition to war policies, he was censured by the North Carolina General Assembly. The legislature complained that he would not follow its instructions and accused him of going against the will of the majority of the state's citizens. Opposed to the instruction of senators by the state legislature, he resigned from the Senate in 1814, convinced that his judgment must be his guide. After his resignation he resumed his legal career and developed plantations in Wake and Bertie counties. His interest in internal improvements was heightened with his election as president of the Neuse River Navigation Company in May 1818.

Stone was also an enslaver. The number of people Stone enslaved varied throughout his life. At the time of the 1800 census, David Stone of Bertie was listed as the enslaver of 59 people. By 1810, the last census before Stone's death, the number of people he had enslaved had reached 98.

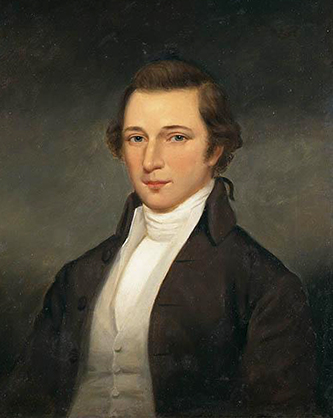

Stone married Hannah Turner on March 13, 1793. Of their eleven children, five died in infancy. Five girls, Rebecca, Hannah, Elisabeth, Sarah, Anne, and one son, David Williamson, survived. Hannah Stone died in April 1816. In June 1817 Stone married Sarah Dashiell, a resident of Washington, D.C.; she died in July 1838. Stone died suddenly October, 7, 1818, at Restdale plantation, where he was buried near the Neuse River, six miles east of Raleigh. A portrait of Stone from the North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, hangs in the house at Hope Plantation, Bertie County, one of his homes.