20 Sept. 1892–23 Sept. 1916

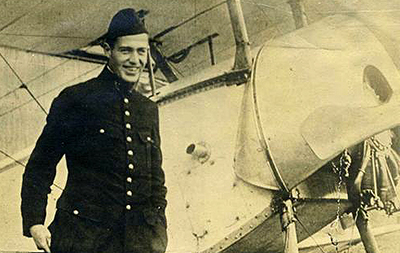

Kiffin Yates Rockwell, American aviator in World War I and pioneer in aerial combat, was a charter member of the Lafayette Escadrille, an American volunteer squadron formed on 20 Apr. 1916, approximately one year before the United States entered the European conflict. He was the first American to shoot down a hostile airplane, the second American killed in aerial warfare, and probably the first American to take up the Allied cause in the war.

Born in the Appalachian mountain town of Newport, Tenn., he was the son of James Chester, a native of North Carolina, and Loula Ayres Rockwell of Marion County, S.C. Because of the father's delicate health, the family moved to the East Tennessee mountains and during his convalescence there Kiffin was born. When the child was almost a year old, James Chester was stricken in an epidemic of typhoid fever and died.

Both of young Rockwell's grandfathers had been Confederate soldiers. Though his paternal grandfather, who served with Clingman's North Carolina Brigade, died about twenty years before Kiffin's birth, his maternal grandfather, Enoch Shaw Ayres, who served from Manassas to the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston's army near Durham, was a companion of his early years. After her husband's death, his mother spent the winters on her father's cotton plantation along the Lumber and Little Pee Dee rivers of northeastern South Carolina but returned to the Tennessee mountains for the summers. Perhaps due to the war stories told by "Marse Enoch" and the coterie of Confederate veterans who came to his home to relive their battle experiences, the family retained a strong pride in Confederate feats of arms, which sent both grandsons—Kiffin and his older brother, Paul Ayres Rockwell—into military careers.

When Kiffin Rockwell was fourteen, the family moved across the mountains to Asheville, N.C., thereafter their home. While attending Asheville High School, he so strengthened his interest in the army that he enrolled in the autumn of 1908 in Virginia Military Institute at Lexington, Va. The next year he received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. After a session at the Werntz Preparatory School studying for the entrance examinations, he concluded that the navy would not see action in his lifetime and he was not attracted to peacetime service. His brother Paul was attending Washington and Lee University, near Lexington, which Kiffin had frequently visited and where he now matriculated. He joined the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity, had a happy college life, and was pointed towards a newspaper career in the university, which, under the presidency of General Robert E. Lee, conducted the nation's first school of journalism. By this time Rockwell had grown into a handsome man: six feet, four inches tall, with eyes of clear blue, he had a charming manner and was a graceful dancer. He was popular with his schoolmates but reserved with strangers; he was never the back-slapping type.

His interest in journalism was intensified by a trip he took at this time through the United States and western Canada in order to discover the locality where he would like to settle. He loved San Francisco and spent several months there, later confiding during the barracks talk in France that life in the Golden Gate city was more like that of France than any other American city he knew. For a time he conducted an advertising agency there; though only nineteen, his height and demeanor made him appear older. After returning to Asheville in late 1913, he went on to Atlanta, Ga., on 1 Jan. 1914, where his brother was engaged in newspaper work. Kiffin joined another advertising agency, enrolled in an advertising correspondence school, and was achieving success in that field when war broke out in Europe.

On 3 Aug. 1914, when Germany declared war on France and President Woodrow Wilson issued his neutrality proclamation for the United States, Kiffin Rockwell, speaking also for his brother, wrote to the French consul in New Orleans volunteering for the French army. Later, at a time when he experienced a presentiment of death, he explained in a letter to his mother: "If I die you will know that I died as every man should—in fighting for the right. I do not consider that I am fighting for France alone, but for the cause of humanity, the most noble of all causes."

Without waiting for a reply from the French consul, the Rockwell brothers left Atlanta for New York and sailed for France on 7 August, well before aerial combat had entered warfare. Kiffin, then twenty-one, had handled firearms since he was ten and sought an infantry assignment. He and Paul joined the French Foreign Legion; for the French, Kiffin's attendance at Virginia Military Institute was a strong point in his record. Both men were severely wounded. In an infantry assault at Nouville-Saint-Vaast on 9 May 1915, Kiffin received a thigh injury that ended his marching and infantry service, while Paul's wound sent him into the French Army Grand Headquarters service. On recovery, Kiffin became one of the first Americans to join the newly formed Escadrille Americaine, soon renamed, upon complaint of the American government, the Lafayette Escadrille.

Airplanes, still in their infancy, and at first used only for reconnaissance, had become machines of combat in the boundless heavens, and air superiority was soon a factor in victory. After brief training and twenty-eight days after the formation of the Lafayette Escadrille, Kiffin, who had had no previous experience in aviation, shot down—on the Alsatian front on 18 May 1916—the first enemy plane credited to this new organization of American volunteers. Thereafter he saw continual combat with a leave in Paris after four months. Meantime, Kiffin had shot down his second enemy plane and had participated in every mission of his squadron. He gloried in the melee of squadron battle. In his first combat mission upon returning to duty, he encountered a two-seater German plane, dived into a dogfight with it, and was hit in the chest with what was described as an expanding bullet that shattered and killed him. The action occurred behind the French lines in the Vsoges sector, and his riddled plane fell into a field of flowers. Rockwell was a sergeant at the time but had been recommended for a commission as second lieutenant.

His funeral was notable, attended by his squadron comrades, fifty British pilots, and numerous French pilots and mechanics; the cortege included a regiment of French territorials and a battalion of colonials. The French government awarded him numerous citations and medals, made his grave a shrine, marked the place where he fell, and placed exhibits in its aviation museum. He also was honored in numerous ways in the United States—by North Carolina and his colleges; in poetry, including memorial poems by Edgar Lee Masters and Paul Scott Mowrer; and in a substantial literature on the Lafayette Escadrille. But perhaps the greatest tribute was that spoken at his grave-side service by the French aviator, Captain Georges Thenault, commandant of the squadron: "His courage was sublime. . . . The best and bravest of us is no longer here."

The Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Newport, Tenn., and an American Legion post in Asheville, N.C., are named in his honor. His letters home have been published in English and French. He was awarded posthumously the Cross of the Legion of Honor.