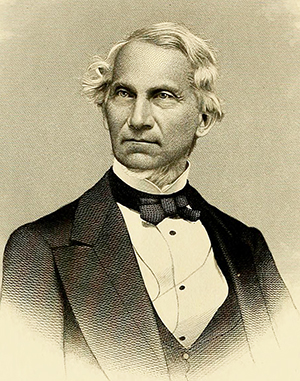

9 Jan. 1803–7 Mar. 1888

Christopher Gustavus Memminger, lawyer, statesman, and secretary of the Confederate Treasury, was born in Nayinghen in the Dukedom of Württemberg, Germany, the only child of Christopher Godfrey and Ebarhardina Elisabeth Kohler Memminger. Christopher was an infant when his father, an officer in the Prince-Elector's Battalion of Foot Jaegers, was killed in the line of duty. He immigrated with his mother and her parents to Charleston, S.C., to escape Napoleon's continuing wars, but there his mother died and four-year-old Christopher was placed in the Orphan's House of Charleston. At age eleven he was adopted by Thomas Bennett, later governor of South Carolina, and was reared in an atmosphere of refinement and opportunity.

Before his thirteenth birthday Memminger entered the South Carolina College in Columbia, the forerunner of the University of South Carolina. Although the youngest in his class, he was singled out for academic excellence and exemplary conduct. After graduation he returned to Charleston and prepared for a career in law.

In time he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives, where, as chairman of the Committee on Education, he reformed the entire public school system of the state and implemented a program of graded schools in Charleston that was considered second to none in the United States. As chairman of a committee on finance for the state, he established a reputation as a sound financier. For thirty-two years he was a trustee of his former college.

Prior to South Carolina's secession from the Union, Memminger played a leading role in the Union States Rights party. He opposed nullification and presented his arguments against it in The Book of Nullification, a widely read satire that he wrote in biblical style. Following John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry, Governor William H. Gist of South Carolina assigned him the task of expressing to Virginians the desire of South Carolinians to unite with them in measures of defense. By his address Memminger appealed to thinking men and prepared their minds for the events that would soon plunge the country into war. Before the year ended, he was won over to secession, becoming an active member of the Secession Convention of South Carolina and heading a committee to draft a statement justifying the state's actions.

At the beginning of the war President Jefferson Davis appointed Memminger secretary of the Confederate Treasury. When he assumed his duties, there was neither money in the Treasury nor paper on which to print it. The Northern blockade prevented the exportation of cotton, the South's only resource that could demand cash. Memminger developed Treasury policies that proved ineffective against the problems of the Southern states during a four-year war, and when he resorted to levying taxes to raise funds, it was too late. The Confederacy collapsed, but responsibility for it lay with the government, not with Memminger, who had frequently been compelled to carry out policies of which he did not approve. Realizing that his job was hopeless, he resigned from office in June 1864.

Memminger sought refuge with his family in Flat Rock, N.C., where Rock Hill, his summer home for twenty-five years, had become a wartime haven for friends and relatives. Earlier he had urged President Davis to move the Confederate capital from Richmond to Rock Hill, believing it could be more easily defended against invasion by Northern troops. But Glassy Rock Mountain, rising behind Rock Hill, harbored renegades at a time when no civil or military law existed to protect the community. The steps of the house were pulled down, portholes were cut in doors, windows and doors were barricaded with sandbags, and slits were cut in the walls so the renegades could be fired on by unseen defenders.

In 1867 Memminger was fully pardoned by President Andrew Johnson, and all of his privileges of citizenship were restored. He returned to Charleston and to the legislature of South Carolina, where, as chairman of Ways and Means, he endeavored to recover the lost credit of the state. He resumed efforts as well on behalf of the South Carolina public school systems for both races. In addition, Memminger had long been among those who advocated a railroad connecting the southern seaboard with the navigable waters of the western Carolinas. With the resumption of construction interrupted by the war, he accepted the presidency of the railroad company for the time necessary to complete the vital link between Spartanburg, S.C., and Asheville, N.C. Then he bowed out of public life.

Memminger was married for forty-three years to Mary Wilkinson, the daughter of Dr. Willis and Leonora Withers Wilkinson. Of their seventeen children, eight survived childhood: Robert Withers, Ellen, Lucy (Mrs. Charles Coatesworth Pinckney), Edward Read, Sarah Virginia (Mrs. Ralph Izard Middleton), Mary (Mrs. Robert Francis Louie Dincotte), Willis Wilkinson, and Allard. After Mary's death, Memminger married her sister Sarah Ann, who survived him.

Memminger died in Charleston at age eighty-five. In accordance with his request, he was buried in Flat Rock beside the grave of his wife Mary in the cemetery of St. John-in-the-Wilderness Episcopal Church, of which he had been a member for fifty years.