1866-1944

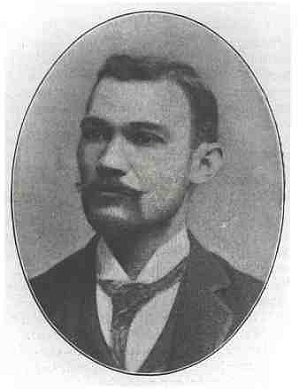

Alex Manly was born near Raleigh in 1866. Family tradition maintains that his father was Charles Manly, who served as governor of North Carolina from 1849 to 1851. There is some confusion about Manly’s father, and Alexander Manly may have been Governor’s Manly’s grandson or nephew instead. Manly’s legal father, Trim, was enslaved on the governor’s plantation. Family tradition also has it that his mother Corrine was an enslaved maid in the household. Manly and his brothers were well educated and attended Hampton Institute.

Manly was the editor of an African American newspaper, the Wilmington Record, which he owned jointly with his brother Frank. In 1895, soon after they had assumed ownership and management of the Record, he wrote: “The air is full of politics, the woods are full of politicians. Some clever traps are being made upon the political board. In North Carolina the Negro holds the balance of power which he can use to the advantage of the race, state, and nation if he has the manhood to stand on principles and contend for the rights of a man.”

The Manly brothers became a target of the Democratic Party in the 1898 political campaign, particularly because of an editorial published in their paper in August 1898. Apparently written by Alex, the article called into question the role of race in male/female relationships. Democratic Party leadership saw the editorial as an insult to white manhood and the sanctity of white womanhood. The article was printed out of context in several papers across the state and became a rallying point. The outcry against Manly’s article became an easily identifiable touchstone for the 1898 political campaign, and many cited it as justification for the violence that followed the election.

Soon after Manly’s article was published, the owner of the building evicted Manly’s printing business. At the same time, a group of concerned black citizens surrounded the press to protect it from impending destruction by a group of white men. Manly then retaliated by proposing in the paper that blacks boycott white businesses. Throughout the rest of the campaign season, Manly and his business were targets of both verbal and clandestine attacks.

Two days after the election which saw Democratic victories across the state, violence broke out in Wilmington. A mob of white men destroyed the Record printing offices on the morning of November 10, 1898. On the night prior to the violence, a Red Shirt mob unsuccessfully searched for him. Manly, aware of the search and the probable danger to his life, escaped from the city with his brother Frank. Some accounts claim that he departed Wilmington prior to the riot, but others indicate that he left on the day of the violence. Tradition holds that Thomas Clawson—editor of the rival Wilmington Messenger—gave Manly the pass code and money to leave town and that he and Frank were light-skinned enough to pass through the checkpoints. A recent history of Wilmington’s St. James Episcopal Church reports that clergyman Robert Strange personally escorted Manly out of the city in his carriage. Manly relocated to Washington D.C. by 1900, and according to some accounts he was first given asylum by Congressman George H. White.

While in Wilmington, Manly was involved in Wilmington civic life as an active member of Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church and was engaged to Caroline Sadgwar at the time of the violence. Caroline, the daughter of prominent community leader and Wilmington native Frederick Sadgwar, Jr., was educated at Gregory Normal School and attended Fisk University in Tennessee. Caroline, a talented vocalist with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, was performing in England at the time of the violence, and as soon as she returned to the United States she married Manly at the residence of Congressman White in Washington D.C. The couple later moved to Philadelphia, where they started a family and Manly worked as a painter. Manly and his family were able to return to Wilmington for visits for many years after the violence—although he may have traveled in disguise. Manly maintained that property he owned in Wilmington was seized for nonpayment of taxes.

Manly became active in numerous activities after leaving Wilmington. He was a leader in the Afro-American Newspaper Council and helped to establish the Armstrong Association, a forebear of the Urban League. He died in 1944.