25 July 1797–4 Nov. 1856

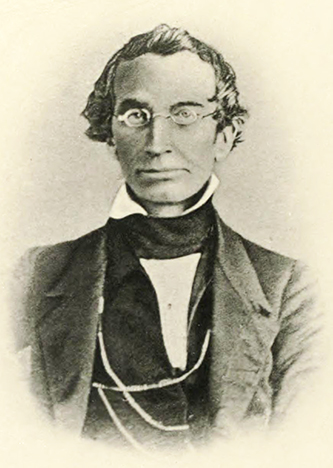

Nicholas Marcellus Hentz, teacher and America's first arachnologist, was born in Versailles, France, the youngest child of Nicholas and Marie-Anne Therèse Daubrée Hentz. He was the brother of Jean Nicholas Richard, Françoise Constance Eleonore, and Jean François Victor. In 1810 the youth began to study miniature painting in Paris, and three years later took up medicine and became a hospital assistant. In 1816, after the downfall of Napoleon, political circumstances in France forced his father to escape to America. The elder Hentz and his wife, with their oldest and youngest sons, settled in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

As a teacher of French and painting, young Hentz resided in Boston and Philadelphia, and then on Sullivan's Island, S.C., where he was a tutor on a plantation. There he intensified his entomological studies with a special interest in spiders. At Harvard he attended lectures in medicine, but abandoned his studies to join the faculty of a boys' school in Northampton, Mass. On 30 Sept. 1824 he married Caroline Lee Whiting of Lancaster, Mass., and in 1827 assumed the "chair of modern languages" at The University of North Carolina. For the next four years he pursued his study of spiders and published a number of articles in scientific journals.

In Chapel Hill, life was not always pleasant. During his second year the trustees ruled that each professor "be in his room on the campus from 9–12, 2–5 each day," and Elisha Mitchell, his noted associate on the faculty, wrote that, although he thought Hentz was "one of the most accomplished Entomologists, perhaps the most accomplished in America," he feared the Frenchman might leave the university, for his field trips required him to "ramble in the woods two or three evenings [afternoons] in the week." In 1829, when the university awarded him an honorary M.A. degree, Hentz revealed to a correspondent that he had then collected about "two-thirds of the American spiders, and that in the South the spiders of a given species are much larger than in the North." In spite of his recognized scholarship, the narrow Presbyterian community at the university frowned upon Hentz's having been reared a Roman Catholic, and suspected him of French revolutionary liberalism. Even the students felt that somehow the study of French was contrary to religious tenets. Though normally genial, the small, slightly built professor was subject to a severe nervous disorder, and then he would become suspicious and jealous. His fits of "ejaculatory prayer," regardless of where he was, disturbed the sedate villagers. Hentz decided to try to improve his locale and his finances.

On 6 June 1831, Mrs. Winifred M. Gales, a close friend of the Hentz family, wrote Jared Sparks that the Hentzes "left Raleigh this day on their way to Kentucky where he has an engagement of 2,000$ a year. For their sakes I rejoice for they were not agreeably suited at Chapel Hill," where the inhabitants persecuted unbelievers "after the most approved manner of dealing with Heretics! There is a great revival amongst the students at Chapel Hill, and Gossip Report says that the Preachers (Missionaries) inculcate the idea that it is adverse to piety and devotion to study profane subjects." After Hentz's departure, French was dropped from the curriculum.

For the next eighteen years Hentz and his wife conducted female academies in Covington, Ky.; Cincinnati, Ohio; Florence, Tuscaloosa, and Tuskegee, Ala.; and Columbus, Ga. In Florence, Hentz joined the Presbyterian church. In 1849 his health began to deteriorate and, after moving to the home of a son in Marianna, Fla., he died there and was buried in the Episcopal Cemetery. From 1850 on, Mrs. Hentz contributed to the family finances by the sale of her widely read fiction.

After Hentz's death, his collection of insects found their way to the Boston Museum. His first scientific publication in 1820 concerned alligators. In addition to three French textbooks issued between 1822 and 1839, he brought out a novel in 1825, Tadeuskund, the Last King of the Lenape, an Historical Tale, about an Indian massacre of 1778 in the Wilkes-Barre region. His masterwork, The Spiders of the United States, with "two new plates from his skillful pencil," was finally published in 1875.

Nicholas and Caroline Hentz were the parents of five children: Marcellus Fabius (1825–27), Charles Arnould (1827–94), Julia Louisa (Mrs. John W. Keyes, 1828–77), Thaddeus William Harris (1830–78), and Caroline Theresa (Mrs. James Orson Branch, b. 1833).