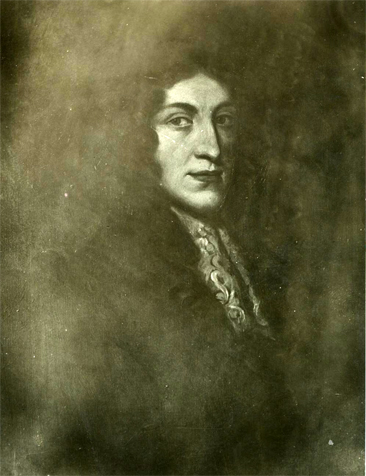

22 July 1621-21 January 1683

Following his mother’s death in 1628, Cooper’s father married Lady Mary Morrison, the daughter of wealthy textile merchant Baptist Hicks. Morrison was co-heiress to Hicks’s estate, and her grandson eventually served as the powerful 1st Earl of Essex. Cooper’s father died two years after his marriage to Mary Morrison and named Sir Daniel Norton and Edward Tooker, both politicians and landowners, as trustees to raise the seven year old Cooper. Cooper attended Exeter College, Oxford and married Margaret Coventry in February 1639. The couple never had children, and Coventry died after ten years of marriage. Cooper then married Lady Frances Cecil, who bore two children, Cecil and Anthony, before her early death in 1654. Only Anthony lived to adulthood.

Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles, a leader in the opposition movement against Charles I, blocked Cooper’s first attempt to enter politics. Holles cited Cooper’s recent marriage to Margaret Coventry, whose father served as Lords Keeper at the time, as constituting a conflict of interest that would compel his sympathies toward the king. In turn, Cooper initially supported the Royalists (or Cavaliers) during the English Civil War. However, Cooper’s loyalties shifted over the years, and correspondence indicates that Cooper had Parliamentarian sympathies. It was during this time period with the Parliamentarians, known as “Roundheads,” that Cooper expressed interest in business. He co-owned a 205-acre sugar plantation in Barbados, which at one point was worked by 21 servants and 15 enslaved people. Cooper sold his share of the plantation in 1654 amid increasing competition from Dutch merchants, likely boosting the English statesman’s foray into international commerce regulation. These campaigns for market power led to the Anglo-Dutch Wars that prevailed for more than an entire century as the English and Dutch fought for control of sea channels and other trade routes.

In 1649, Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland, appointed Cooper to the Council of State after Charles I’s overthrow and execution. Cooper, however, became distanced from Cromwell, who disbanded the parliament of which Cooper had been a member in January 1655. With the rise of the Convention Parliament five years later, Cooper was once again appointed to the Council. He and his colleagues restored the monarchy to Charles II, the eldest living son of Charles I, at which time Cooper was reportedly “a firm friend to the king.” This connection led to Cooper’s privileged seats on various commissions, including the council of trade.

In 1663, the king granted the Province of Carolina to eight individuals. Cooper was one of those men, and he came to lead the management of this huge tract of land in North America, which Parliament named from the Latin Carolus in honor of Charles I. Cooper also had a connection to the Raleigh name, as Sir Walter Raleigh’s son, Carew Raleigh, married the widow of Cooper’s maternal grandfather. The Ashley and Cooper Rivers in South are named after Cooper himself. Apparently Cooper liked the water so much that he sent a letter to Sir John Yeamans, then governor of the Province of Carolina, requesting “12,000 acres in some convenient healthy fruitful place upon the Ashley River” for his own enjoyment. (The Ashley River is in present day South Carolina.)

It was random chance that Cooper, visiting Oxford for a medical appointment, made an acquaintance with the eminent Enlightenment philosopher John Locke. Locke was a medical student at the time, not having written any of the philosophical works that would later bring him to fame as a political thinker. He was having difficulty working toward his medical degree, yet he managed with great skill to drain a dangerous abscess growing inside of Cooper’s body. Locke subsequently fit a drainage tube into the affected area that Cooper wore for the rest of his life. This is when their friendship began, as well as when Locke joined Cooper’s management team as secretary.

Many historians have suggested that Locke was not only a participant in the administration of the Province of Carolina but also an active decision-maker when it came to policy. It is likely that Cooper relished hearing Locke’s opinion on governmental matters. Evidence confirms that Cooper possessed an early draft of Locke’s celebrated “Essay Concerning Human Understanding” in 1681, nearly one decade before the work officially appeared in England.

One year after the completion of “The Fundamental Constitutions,” Cooper realized that Charles II had secretly signed the Treaty of Dover with King Louis XIV, who at the time ruled France. The agreement called for an alliance between the two nations under the condition that France pay an annual stipend to Charles II and that the English king eventually convert to Catholicism and begin urging his kingdom in the same direction.

Cooper disagreed with the treaty’s contents immensely but quelled his opposition in light of Louis XIV’s desire to wage war against the Dutch Republic, whose merchants competed with Cooper’s sugar plantation in the 1650s. Charles II appointed Cooper as Lord Chancellor in November 1672. Locke stayed on as Cooper’s secretary and often acted as his closest political adviser, “conducting research [and] writing speeches … in connection with Shaftesbury’s trading and colonial interests”. It is also notable that Cooper moved politically leftward (i.e., toward classical liberalism) during this time, likely catalyzing his split with Charles II and Catholicism in general.

The next nine years of Cooper’s life consisted of political battles over England’s alliances, the role of the king in national affairs, and increasing presence of Catholicism that many believed would lead to institutional popery. Entertainment, though, sanctioned by the king, tended to satirize the political environment in favor of the Court. Thus, “The Roundheads, the citizens, the Presbyterians, the opposers of the Crown, above all the foremost Liberal of the day, Anthony Ashley Cooper, later the Earl of Shaftesbury, were fair game” and frequently the object of ridicule.

At the same time, complaints were getting louder in the Province of Carolina. Citizens reacted fiercely to both the Navigation Acts, which dictated trade routes throughout North America, and the territorial government’s failure to protect the colonists from Indians, pirates, and other invading forces. These resentments culminated in Culpeper’s Rebellion in 1677, lasting about one year until the rebellion leader’s arrest in England.

Cooper founded the Whig Party in 1678 in order to contest the king’s ideal of absolute rule in favor of constitutional monarchy. A few historians are wary of using the term “founder” when referring to Cooper, but it is generally agreed upon that he was the key player leading the party’s strategy in Parliament. Cooper spearheaded the passage of the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, at which point the king had already tried to bribe individuals, including Governor Henry Wilkinson, who would incriminate Cooper in a plot to seize the Crown. Tensions quickly rose, and Charles II charged Cooper with high treason in 1681, forcing him to leave England forever.

Cooper’s health deteriorated during his emigration voyage to Amsterdam. Expecting the worst only a few months later, he drew up a will. In it, he wrote a poetic reminiscence of his life: “Yet still, in every state, I walk’d secure, grave with the king. . .Thus, all my shams discover’d, I, poor I, was forced to, although my wings were clip’d, to flie. Nay, though no legs I had, my gate was fleet, oblig’d to travel, though I had no feet; from justice (all my crimes laid at my door) found power to run, who cou’d not crawl before”. Cooper died on January 21, 1683. Shippers carried his body back to Dorset three weeks later, where he lays at the place of his birth, Wimborne St. Giles.