1692–7 Jan. 1750

Eleazer Allen, colonial official, was born in Massachusetts to the former Mary Anna Bendall and Daniel Allen, a Harvard M.A. and librarian of the college. After the death of his father sometime before 1720, young Allen went to Charleston, S.C., and became a merchant, apparently interrupting his college studies to do so; in about 1726 he returned to Massachusetts briefly and was graduated from Harvard. About 1722 he married Sarah Rhett, the eldest daughter of William Rhett, a leading figure in South Carolina society and business. Another of Rhett's daughters married Roger Moore, and through this family connection, Allen became interested in the lower Cape Fear region of North Carolina, where Roger Moore and his brother Maurice were among the principal landowners. In 1725, when Governor George Burrington, during his proprietary administration of North Carolina, began making large land grants to encourage settlement in the lower Cape Fear, Allen was a leading beneficiary. At some time between 1725 and his permanent move to North Carolina in 1734, Allen constructed a plantation just north of Roger Moore's Orton. He named his home Lilliput for the imaginary country in Gulliver's Travels.

When George Burrington was chosen as first royal governor of North Carolina in 1730, he nominated Eleazer Allen to a council seat. Although confirmed by the Privy Council in London, Allen did not accept his mandamus as a councillor during Burrington's administration (1731–34). He was serving as clerk of the lower house of assembly in South Carolina at the time and chose not to leave.

Allen was also named as a councilor in Gabriel Johnston's royal instructions, and he attended Johnston's swearing in as governor of North Carolina on 2 Nov. 1734 at Brunswick. The new chief executive then administered the oaths of a councilor to Allen. This early association with Johnston and dissociation from the controversial Burrington, combined with his social position, wealth, and intelligence, made Allen a favorite with the governor even though the two men had not known each other previously. On 6 Mar. 1735 Johnston and the council appointed Allen receiver general of quitrents for the colony, one of the most lucrative offices in the province. Although there was already a receiver general for North Carolina holding a Crown commission, he resided in South Carolina, and Johnston was anxious to have such an important officer in close proximity. The board of trade would ultimately commend the governor's move. As was often the case in colonial America, appointment to one office led to others. Almost as soon as he had arrived in North Carolina, Allen was made a justice of the peace for New Hanover County. He served on the commission that settled the boundary between North and South Carolina, and all of the commissioners from both colonies met at Lilliput on 23 Apr. 1735 to establish guidelines for the survey. In March 1736 Allen became precinct treasurer of New Hanover; by October he was a judge of the court of oyer and terminer.

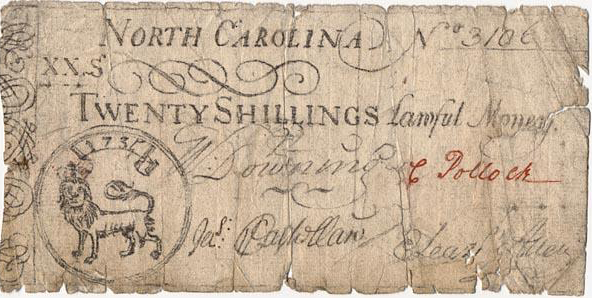

As the lower Cape Fear region began to burgeon into the trade center of the colony, Governor Johnston became increasingly disaffected with the leading landowners there, especially the Moores and their allies (called "the Family" by some historians, since most of its members were related by birth or marriage). Relations between the governor and Allen, a leading "Family" figure, became strained. By early 1740 Allen was allying himself with some of his fellow councilors, Nathaniel Rice, Edward Moseley, and Roger Moore, to oppose Johnston's efforts to shift the center of activity in the lower Cape Fear from "the Family" -dominated town of Brunswick to Newton (later Wilmington). Governor Johnston was eventually successful, and by May 1742 Allen had patched up his quarrel with the governor and accepted a royal commission under the sign manual as receiver general. In November 1743 he was named a surveying officer in the mapping of the Granville District. In March of the following year Receiver General Allen laid before his fellow councilors his complaints about quitrent collections in North Carolina. He objected primarily to the lack of currency in the colony, which forced him to accept commodities as payment. Although the governor and council ruled that quitrents would be payable in the future only in specie, there was little machinery for enforcing such a decree.

Whatever problems Allen may have had with certain of his duties, his career continued to prosper. In March 1748 he was made an associate justice of the general court, which was, for all practical purposes, the highest criminal and civil court in North Carolina. During his last year of life, Allen held two of the most important offices in the province. In October 1749 he succeeded the deceased Edward Moseley as public treasurer for the southern counties, an office to which he was elected by the General Assembly. Later in 1749 Allen was elevated to the chief justiceship of the general court, upon the death of Enoch Hall.

At the time of his death the following year, Allen was a wealthy man who owned 1,285 acres of land and enslaved about 50 people. The inventory of his estate showed sizeable holdings of silver and china, but most impressive was a library containing more than two hundred English and fifty French titles. Reflecting his interests as a man of culture and a provincial officer, Allen owned such books as Plutarch's Lives, Ovid's Metamorphoses, several navigation and surveying manuals, Fielding's Tom Jones, and Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding.