Approach of World War I

In the summer of 1914, most North Carolinians, like most Americans, knew little and cared less about the small country of Serbia in the Balkan Mountains of central Europe. Probably they had never heard of Sarajevo. When Archduke Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated there, North Carolina newspapers like the Charlotte Observer carried long descriptions of the elaborate funeral for the couple. Far more important in the news was the involvement of the United States in a revolution in Mexico that had started in 1910.

In the summer of 1914, most North Carolinians, like most Americans, knew little and cared less about the small country of Serbia in the Balkan Mountains of central Europe. Probably they had never heard of Sarajevo. When Archduke Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated there, North Carolina newspapers like the Charlotte Observer carried long descriptions of the elaborate funeral for the couple. Far more important in the news was the involvement of the United States in a revolution in Mexico that had started in 1910.

But suddenly on July 25, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian government sent an ultimatum to Serbia. It ordered the country to submit either to annexation or else risk war. The ultimatum was sent because the archduke's assassin was a citizen of Serbia.

Most Americans hoped that if war began only Serbia and Austria-Hungary would fight. They did not see why other nations should become involved. What they did not realize was that a network of alliances would automatically pull in all the big European countries on one of the two sides. Within a few days the alliances brought Russia, Germany, France, Britain, Italy, and Turkey into the war.

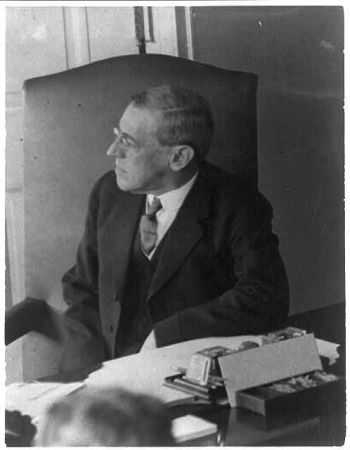

On August 4, President Woodrow Wilson announced that America would remain neutral. A North Carolina editor said, “The impending clash may shake the nations, but thank God! our government is safe!” Life as usual resumed.

The event that brought the United States into the war three years later was Germany’s decision to turn loose submarines, or U-boats, in the Atlantic. Neither side was winning the war, and both were all but exhausted. A stalemate had developed. To break the stalemate, Germany had two choices. One was to break the British blockade of German seaports to get more food and ammunition. The other was to blockade British ports with German submarines to prevent food and ammunition from reaching Britain. Germany decided to blockade Britain.

In February 1917, the German government announced that it would begin “unrestricted submarine warfare.” Only one ship per week from the United States would be allowed to travel to England without being attacked. The Charlotte Observer correctly feared that this would bring America into the war. The Greensboro Daily News proclaimed, “The Evil Day Has Come” The Robersonville Herald, still trying to remain neutral, urged a national referendum on going to war. Those who voted for it should go to the front and fight. Those who voted against war could stay home.

Nations declare war on each other for economic reasons, for self-defense, for territorial gain, or for glory. America had some of all of those reasons but also national pride to protect. Most Americans were not going to let Germany tell them what they could and could not do. In March, German submarines in the Atlantic Ocean sank four ships from the United States all within a week of each other. These losses angered Americans. Said the Charlotte Observer, “The sooner war . . . shall get under way . . . the sooner will the war be ended and peace declared.”

President Wilson called a joint session of Congress. On the evening of April 2, he asked for a declaration of war, saying, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” His speech was very stirring and is still quite famous. He spoke of being on the side of “the right,” of democracy, of liberties of small nations, and of peace and safety for all nations. The Greensboro Daily News praised him: “He has been bold enough to base the fight on the rights of mankind.”

Both of North Carolina’s senators agreed with the president. Only six senators voted against going to war. More members of the House of Representatives were against it, including the majority leader of the Democratic party, Congressman Claude Kitchin from North Carolina. When the roll was called for the vote, Kitchin explained to fellow members of the House why he was going to vote against war.

Kitchin believed that Europe should fight its own wars and that Serbia and Sarajevo had nothing to do with the United States. He did not want American blood to be shed in a quarrel over far away places and felt that such a war was wrong. Members of the House applauded Kitchin's courage and resolution. But when they voted, their decision was 373 for war and 50 against.

Once the decision was made, most North Carolinians, including Kitchin, were patriotic and worked hard to support their country. Governor Thomas W. Bickett said, “This is no ordinary war. It is a war of ideals.”

Sarah McCulloh Lemmon, a prolific writer of North Carolina history, served fifteen years as head of the Department of History at Meredith College.

Additional resources:

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." North Carolina Digital History. LEARN NC. https://web.archive.org/web/20160311034610/http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newcentury/3.0 (Accessed May 12, 2022).

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

Image credits:

"Woodrow Wilson: One of first Cabinet Meetings." 1913-1924. Library of Congress. National Photo Company Collection. Call no. LOT 12281. Online at http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b32227. Accessed 8/31/2012.

1 May 1993 | Lemmon, Sarah McCulloh